"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

Europe needs Hungary ... which has never allowed itself to be defeated.

János Decsi Baranyai , the learned teacher of the Marosvásárhely Reformed College, recommended the János Thelegdi :

"... Anyone can learn these letters in a very short time, very easily. Why do I consider these letters worthy not only to be taught in every school and instilled in children, but also to be learned by all our compatriots, children, old people, women, nobles and peasants, in a word, all those who want to be called Hungarian you."

What is runic writing?

Runic writing is an old type of writing consisting of characteristic linear, mostly straight-stemmed letters, which can be used on all writing media (stone, wood, metal, parchment, paper, silk, etc.). Other peoples also had runic writing (for example, Pelasgians, Phoenicians, Etruscans, Greeks, Germans, Turks), but my research into the history of writing proves that these developed from the runic writing of the Hungarians' ancestors.

Hungarian runic writing is one of our nation's most valuable cultural and historical treasures, and its use is a noble form of tradition preservation. Unfortunately, it has not yet been included in the curriculum as a subject, although special classes can be organized to teach it. Fortunately, there are some teachers who mention it, such as Ferenc Bánhegyi in his textbook Home and Folk Knowledge published by Apáczai Kiadó.

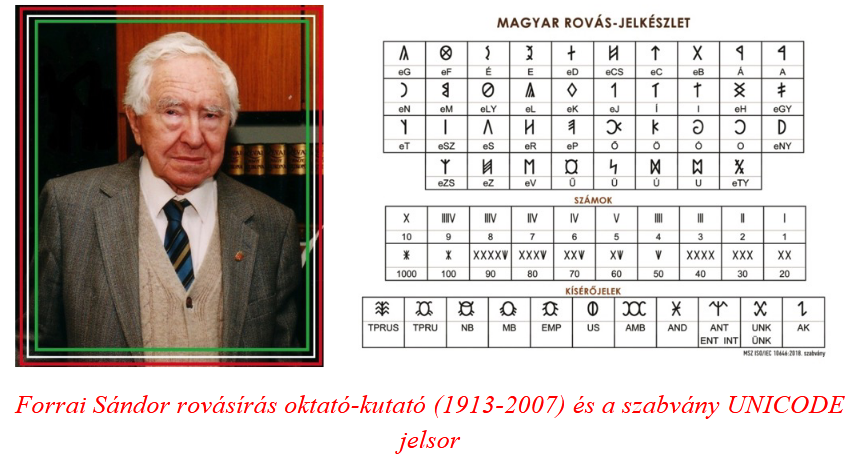

Sándor Forrai received the Hungarian Heritage Award for his work in 2013, and in 2014 runic writing was included in Unicode, the international standard for writing systems. However, none of them was done on official recommendation, but on the initiative of private people branded as "dilettantes".

Our chroniclers and historians also remembered our old writing, among others Simon Kézai, Márk Kálti, János Thuróczy, Antonio Bonfini, Antal Verancsics, István Szamosközi, Mátyás Bél and called it Scythian-Hun writing. At the beginning of the 20th century Mihály Tar , who learned it from his ancestors, and János Fadrusz , one of our greatest sculptors, the creator of the Matthias statue in Cluj-Napoca, gave the name runic writing to our old writing, which perfectly expressed its character that could be written on wood, carved in stone, or written on paper. It is also called the Székely-Hungarian runic script, as most of its memories have been preserved for us by the Székely people. Its survival after 1945 is also due to the scout movement.

Our chroniclers and historians also remembered our old writing, among others Simon Kézai, Márk Kálti, János Thuróczy, Antonio Bonfini, Antal Verancsics, István Szamosközi, Mátyás Bél and called it Scythian-Hun writing. At the beginning of the 20th century Mihály Tar , who learned it from his ancestors, and János Fadrusz , one of our greatest sculptors, the creator of the Matthias statue in Cluj-Napoca, gave the name runic writing to our old writing, which perfectly expressed its character that could be written on wood, carved in stone, or written on paper. It is also called the Székely-Hungarian runic script, as most of its memories have been preserved for us by the Székely people. Its survival after 1945 is also due to the scout movement.

Our runic writing developed together with our Hungarian language, because it contains signs for all our sounds, so we can say that it is ours and we did not take it from anyone.

It belongs to alphabetic writing, where each sound is represented by a separate letter, so we can easily write down even the most abstract concept. When the 10-11. In the 19th century, we had to switch to the Latin script, in which there were no signs for our 13 sounds (TY, GY, NY, LY, SZ, ZS, CS, K, J, Á, É, Ö, Ü). Thus, he was unfit to write down our beautiful Hungarian language and strongly rejected our written language.

Runic writing is proof that a significant part of our common people knew how to write letters, in times when even the Frankish emperor, Charles the Great , could not write, according to the testimony of Einhard The Szarvasi Tűtártó dates from this period (7th-8th century). It was found in a commoner's woman's grave and a text consisting of 60 runic signs was scratched into the sheep's bone by its literate maker.

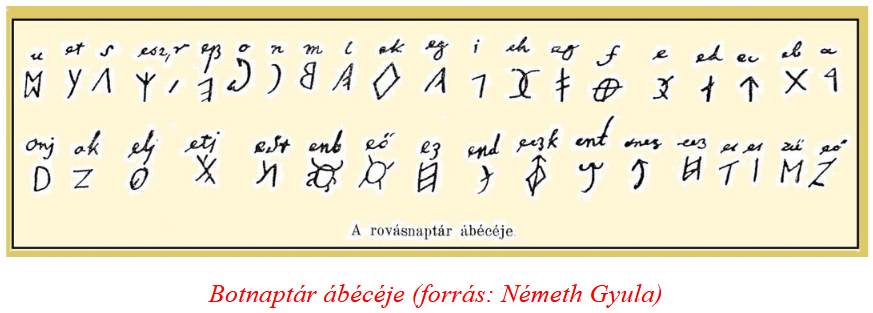

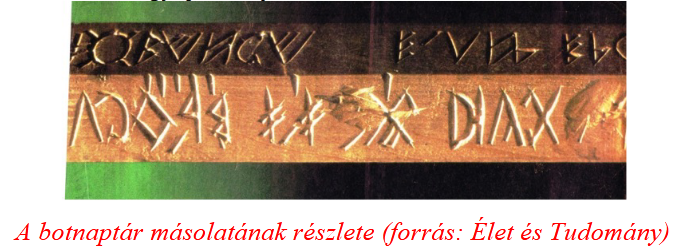

Christian name festivals on the Rovaniemi stick calendar

Among our best-known runic monuments is the Gyergyószárhegy, approximately 200-word runic stick calendar from the period between the 11th and 13th centuries. Survived in a copy by the Italian Count Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli Marsigli is undoubtedly the 17-18. the most influential foreign personality of the 20th century. Not only because of his adventurous life, but also because of his cultural heritage. He was born in Bologna in 1658 and died there in 1730. In the intervening time, however, he did not stay at home much. Among other things, he was a cartographer, hydrologist, botanist, astronomer, book collector, writer, draftsman, painter, naturalist, military engineer, and secret agent. He once escaped from Turkish captivity hiding in a sheepskin. He was a slave of the Turkish Pasha in Buda, later the imperial general who recaptured the castle there.

Marsigli came to our country in the fall of 1682, at the age of 24, as a volunteer for the battles against the Turks, where he spent more than twenty years with minor interruptions.

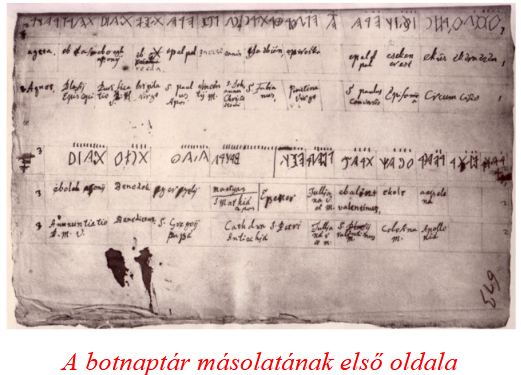

In 1690, Marsigli copied a Székely calendar hung on a stick on Gyergyószárhegy, perhaps in the Franciscan monastery or in one of the chapels there, thus saving our most extensive runic record.

The calendar consists of three parts: 1. Christian holidays and name festivals of notables of the church, 2. Biblical city and personal names related to the life of Jesus, 3. Miscellaneous notes. In addition to these, Marsigli's manuscript also contains a runic alphabet.

More than two hundred words could be read on the stick, which means that it is about 130-150 cm. long, and the width of its four sides is 2-3 cm. it could be. Marsigli sent the staff and the copy, or just the copy, home to his collection, which is kept in the University Library of Bologna. A copy of the stick calendar can be found in volume 54, where Marsigli wrote the following in Italian: "A wood-carved collection of the language of the old Scythians of Székelyland, which displayed a calendar of moving* holidays for the use of the first converts to the Catholic faith, and which I collected myself from the same piece of wood and sent to my collection in Italy when I blocked the passes of Transylvania." (*We are not talking about the calendar of moving but permanent holidays).

Dr. Gyula Sebestyén for making the stick calendar a public domain , who made a study and deciphered it and published it together with photographs in the book A Magyar Róvasírás Authentic Memories, published in 1915. According to his opinion, the calendar is from the Árpád era.

The number of letters in the calendar would be 914, but the experienced Roo used abbreviations, i.e. contractions, ligatures, and vowel omissions in order to save space, so the number of signs became 671. Due to wear and tear, the stick calendar has been rewritten and supplemented from time to time. The first copy may have been made at the time of the conversion to Roman Christianity, i.e. in the 11th century, when the faithful knew the runes even better than the Latin letters. Hungarian saints include István, Imre, László and Erzsébet. According to them, it was also added in the 13th century.

There are six feasts of the Blessed Virgin Mary on the calendar, the days from November 21 to December 13 have been omitted, perhaps due to a copying error, so the feast of Mary on December 8 is not included. The last word of the Botnaptár is the word ÁLDÁS, the greeting of the ancient Hungarian religion.

Zoltán Bárczy, a researcher of runic writing, made a copy of the runic staff from the thorn-free and spasm-free maple (maple, larch) and presented it to Sándor Forrai. At the request of the scientific cartographer György Balla Kisari Ferenc Gurmai , the woodcarver of the Museum of Ethnography, put three copies of the Székely calendar on a maple stick. One of Gurmai's copies was taken by György Balla Kisari to Bologna, where it was included in the collection containing the count's legacy.

Zoltán Bárczy, a researcher of runic writing, made a copy of the runic staff from the thorn-free and spasm-free maple (maple, larch) and presented it to Sándor Forrai. At the request of the scientific cartographer György Balla Kisari Ferenc Gurmai , the woodcarver of the Museum of Ethnography, put three copies of the Székely calendar on a maple stick. One of Gurmai's copies was taken by György Balla Kisari to Bologna, where it was included in the collection containing the count's legacy.

Among the foreign scientists, perhaps Marsigli did the most to preserve the natural and cultural historical treasures of the Carpathian Basin, at least on paper. However, he formed his opinion about Hungarianness through the lens of the Habsburgs who employed him. When the French Sun King, XIV. Lajos wanted to send him to help the freedom struggle in Rákóczi, but Marsigli refused because "according to his understanding, he does not fight with rebels against the lawful ruler" (Gy. Kisari Balla 2005).

Among the foreign scientists, perhaps Marsigli did the most to preserve the natural and cultural historical treasures of the Carpathian Basin, at least on paper. However, he formed his opinion about Hungarianness through the lens of the Habsburgs who employed him. When the French Sun King, XIV. Lajos wanted to send him to help the freedom struggle in Rákóczi, but Marsigli refused because "according to his understanding, he does not fight with rebels against the lawful ruler" (Gy. Kisari Balla 2005).

In my book published in 2003, I wrote this about Marsigli: "...he deserves to be chosen as an honorary Hungarian and maybe in better times Mr. Forrai's dream of erecting a statue to him in Ópusztaszeren will come true." This enthusiasm is now overshadowed by the fact that the count did not recognize the significance of the Rákóczi War of Independence. With his experience as a military engineer, he would surely have led our freedom struggle to victory, thus saving thousands of precious Hungarian lives and obtaining political advantages for our country that are still valid today. You can read more about his life Jónás Beliczay, Sándor Forrai, György Balla Kisari, Gyula Sebestyén, Endre Veress, and László Vékony .

The parts of the series published so far can be read here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8.

Klára Friedrich's writing was published by

Ferenc Bánhegyi

(Cover image source: meska.hu)