"The rush of time screams in your ears: enough of passivity. What up until now was medicine and perhaps protection, but in any case honor, is now poison and cowardice. I call out the slogan: we must build, reorganize for work.

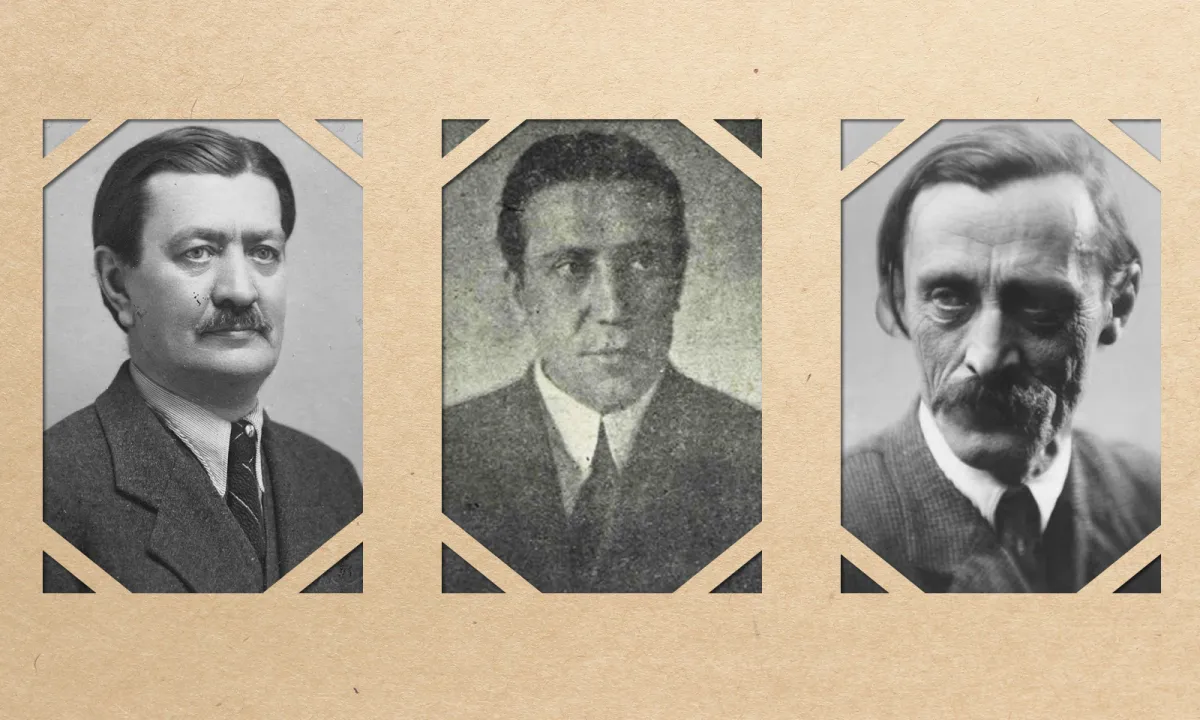

I call out the goal: the national autonomy of Hungarians. But I call out once more: those who are cowards, those who hesitate, those who want to negotiate, do not belong among us, because they are our real enemies: our traitors. This is what I call out and I want to believe that I will not be just a word that cries out in the wilderness" - this is how Károly Kós concludes his memorable introduction to the Hungarians of Transylvania, Bánság, Kőrös-vidék and Máramaros. to the pamphlet entitled (the full text can be read HERE ), which marked the breaking of the flag of the Transsylvanian idea in 1921, and announced the policy of action, the will to live, and a realistic assessment of the situation for the Hungarians of Transylvania in the face of paralyzing passivity. Kós wrote the manifesto together with István Zágoni and Árpád Paál, and although it turned out to be a milestone, its centenary remained in obscurity.

foter.ro conducted a longer interview about the reasons for this with historian Tamás Lönhárt, associate professor at Babeș–Bolyai University in Cluj, a good connoisseur of the era. The historian said:

I am a supporter of building a Transylvania-centric perspective, since Budapest and Bucharest have told their own stories in the last three years. We encountered several different historical narratives, although there is still no unanimous, common position regarding what happened at that time.

However, the Transylvanian system of criteria prevailed very little, both in the Budapest and Bucharest narratives. After all, the Budapest-centric thinking related to the period from the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy to the Council Republic and the Horthy regime elevated the narrative about Transylvania to a kind of central grievance story. Transylvania appears on the level of grievances, pains, and traumas, and not as an independent, acting entity, a colorful and exciting story of elite groups with their own positions. It is important to add our own Transylvania-centric perspective to the Budapest and Bucharest perspectives. And from this point of view, the centenary of 1921 is considered a significant political memory moment.

With the power of hegemonic discourse, Romanian historiography is only willing to consider the Romanian National Assembly in Gyulafehérvár. Hungarian historiography in Budapest outlines the history of the tension between the Gyulafehérvár National Assembly and the Károlyi government, but the Transylvanian Hungarians – Cluj-Napoca or Székelyföld – are also secondary or absent from the central narrative.

Therefore, it is important not only for Bucharest, but also for Budapest, to rearrange these symbolic dates based on the Transylvanian perspective, and to integrate the facts and sources into our self-knowledge and our own Transylvanian identity narrative, taking into account the aspects of historical source criticism.

It is time to leave the memory policy schemes in Hungary and Romania and examine more thoroughly the history of the Hungarian, Romanian, Saxon, and Swabian regional and local processes of the era in Transylvania: what the Trianon period looks like from Transylvania, and the period of resumption after Trianon.

"Károly Kós's lyrical, heartfelt introduction is usually known from the word Kíáltó, and I confess that I can't read this text without emotions, even after a hundred years. But this fragment of the word Kialtó, its very core, its true content, István Zágoni's text on self-organizing society, and Árpád Paál's concluding remarks on the ways of political integration have not been quoted for a hundred years. It would be time to re-read the Exclamation in its entirety and realize that it is not just an expression of an emotional position, but a political, social, and economic self-determination project, a program to create an autonomous community."

The word Exclamation had a wake-up effect: in the face of unfounded hopes, it says that we can only become active builders of reality if we step out of our comfort zone, do away with illusions, assess realistic possibilities, set ourselves tasks and do not expect protection from external forces , which are no longer there - this is the real value of the Exclamation word. When Károly Kós writes that those who follow the waters should go, because they are only hindering us, this also means that those who expect miracles are not able to assess the situations of reality that sometimes require compromises in time, and thus in the turning moments you lose the opportunity to make a good decision.

However, this lack of illusion coexists with idealistic utopias that follow the zeitgeist. Árpádék Paál treated the Wilsonian principles of self-determination as an actual, pragmatic political program. We now know that they set excessive expectations, but at the time these principles seemed like a real stumbling block to a lot of people.

And let me mention another contradiction: while as a simple Transylvanian Hungarian I hope for the reality of the Transsylvanian idea, as a historian I have to question its success, from the perspective of a hundred years. After all, to what extent could the Transylvanian Hungarians have an actual negotiating position vis-à-vis the Transylvanian Romanians, who were the absolute winners of the Trianon decision, even with all their resentment towards Bucharest? Or with the Saxons, who, starting from the experience of Hungarian centralism that eliminated their autonomy, initially considered the Greater Romania project promising? Under such circumstances, how much chance did joint action, the program of Transsylvanian unity have? - concluded the historian.

Source and full article and photo: foter.ro