I watched the documentary entitled Áldozatok 2006, about what happened in the days and weeks after the Öszöd speech was made public, and then on the 50th anniversary of the 1956 revolution and freedom struggle.

With this, as with Elk*rtukk, after the news about the beginning of the film's work appeared, the oppressed, but very extensive part of the Hungarian public, which has been dancing continuously on the border of existence and non-existence for ten years, was permeated by the emphatic opinion that a propaganda film is being made.

This lasted until at one point Fruzsina Skrabski, the film's director and producer, announced that the former journalist of Index, founder-editor-in-chief of Átlátszó, Tamás Bodoky, who wrote a book entitled Túlkapásoks about the police measures of 2006, was also participating in the production, and who got involved in the project with the idea that he would quit if there was propaganda. This put a stick between the spokes of the oiled rolling wheel. Suddenly, the potentiometer of the choir, which in every case advocated propaganda without thinking or considering, when any embarrassing, perverse, intolerable aspect of the functioning of the Hungarian left over the past thirty years was discussed.

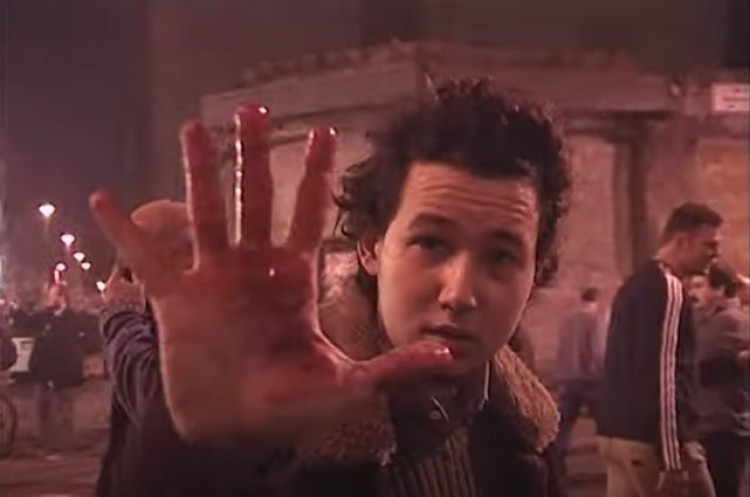

People are horrified to look at the pictures from fifteen years ago, the beatings and kicks of defenseless people lying on the ground, the torture of the policeman in the wrong equipment for the TV headquarters, ordered to be the victim, listening to the accounts of the tortures, and thinking about how they can sink into the public knowledge. below the surface, how the veil of oblivion can fall on them. How can they become a negligible moment of the battle of narratives, can they be classified euphemistically as "controversies of the past"? And of course, it also raises the question of where we will end up, what we can become in the end, if we are unable to talk clearly about similar events, to draw a line between what is still tolerable and what is unacceptable for any reason?

It has been discussed many times that there is a need for a national minimum, some kind of set of values that everyone can agree on, that everyone accepts. The events of 2006 could even have been the basis for this to happen, since it can hardly be disputed that the group abuse of defenseless people lying on the ground is outside the range that a state can afford against its citizens, and who instigated it does, whoever allows this, whoever lets the perpetrators run, must be held accountable.

Not only did it not become a norm, but it did not even become an exhaustive, meaningful discussion that held the promise of clarification. What happened with the unprocessed and buried past happened: it started to emerge. The one who started the whole series of events was the fact finder from Ószöd, who was able to respond to the president's statement that his actions had caused a moral crisis by saying that he was a "Lárifarian", so Ferenc Gyurcsány is here, and besides the fact that he consciously worked to grind the parties of the left, including those who once formulated their identity precisely against his politics, is preparing to return to power at the head of the largest party in the opposition coalition.

And if 2006 didn't become a national minimum, it did become a left-wing minimum, but not because of its rejection, but because of its defense, since Péter Márki-Zay also started to defend the Ószöd speech, and unfortunately, that brings with it the disguise of everything that follows. But this is not really new either, for fifteen years left-wing politicians and intellectuals have been trying to clean up the unwashable. Let's remember the cynicism of Gábor Kuncze when he called Márius Révész, who suffered a head injury, Martírius.

Some with rubber sticks, sword blades, rifles, some with words.