77 years ago, on December 22, 1944, the Red Army issued the order on the basis of which men and women were transported from Hungary to the Soviet Union on Malenkoj robots. "Little work" is forced labor for years - clearing rubble, construction, mining, etc. - was in the Soviet Union.

Already during the Second World War, the leadership in Moscow developed plans for how the countries that attacked the Soviet Union could compensate for the damage they caused. Among the ideas was that the vanquished would not only pay with material goods, but also participate directly in the reconstruction of the Soviet Union with their labor.

The Red Army, which entered the territory of Trianon Hungary in September 1944, issued its order number 0060 on December 22, with which it ordered the mobilization of able-bodied German men aged 17-45 and able-bodied German women aged 18-30.

According to this, those who opt out of the mobilization will be brought before a court-martial, and their family members, as well as their "accomplices", will be severely retaliated against. The Soviet internal affairs soldiers who carried out the order - although they were supposed to fill the workforce exclusively with Germans - took everyone indiscriminately, for them it was only important to herd the number of people determined by their commanders for forced labor.

When describing the events, historians can often only rely on the recollections of the dwindling number of survivors, woven into legends. According to oral tradition, the "Russian" soldiers used to reassure themselves: "malenkaja rabota", meaning "small job".

The people involved who did not know Russian understood this as "malenkij robot", and this is how the term took root. More than once, the soldiers stopped passers-by for identification, who were then put on trucks and taken away, without their relatives knowing anything about their fate.

Source: multkor.hu

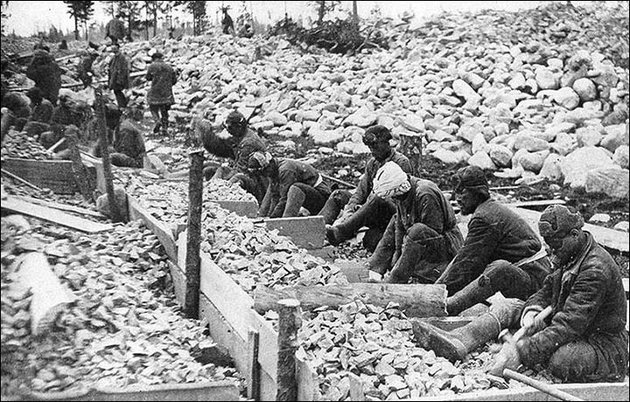

"Little work" is forced labor for years and years - clearing rubble, construction, mining, etc. - was in the Soviet Union. At least one-third of those who were deported perished there, the majority were able to return home by 1949, several thousand were no longer in the territory of Hungary, as their homes were transferred to one of the neighboring countries. They received no help from the communist Hungarian, Czechoslovak, Romanian and Soviet governments, the Hungarian official bodies treated the forced labor as a "prisoner of war case".

Although at that time no one could feel safe even on the streets of Budapest, the Swabians and Transcarpathian Hungarians were the worst. Around 32,000 Germans from Hungary were already deported in a few weeks at the turn of 1944-45, and from November 1944, more than ten thousand Hungarian and German men were called up for reparation work in Transcarpathia. They were sent from the Solyva concentration camp to the infamous Gulag labor camps, the few survivors were considered war criminals in the Soviet Union.

The summary report of the Directorate of Prisoners of War and Internal Affairs of the Soviet People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs on December 20, 1949 stated the number of Hungarian prisoners at 534,539, one-third of whom were civilians. Since they were registered in the Soviet camps, this does not include those who died in concentration and transit camps, as well as during transportation, as well as tens of thousands of Hungarian soldiers who were captured and died along the Don in January 1943. The number of prisoners could thus have been 600-700 thousand, according to other estimates it could have reached up to 900 thousand; the number of those executed and those who died due to the circumstances can be estimated at around 200,000.

Most of the survivors returned home sick, many became unable to work, and until the end of the 1980s they could not speak of their ordeals. A particularly tragic fate befell the political convicts, who from 1949 were sent to the concentration camps for political convicts established at the time within the Gulag. Of the approximately 85,000 Hungarians who were imprisoned in them, only five or six thousand were released, most of them returned home in 1953, but they were treated as political enemies at home until the Soviet rehabilitation.

On May 21, 2012, the Parliament decided that November 25 would be the day of remembrance for Hungarian political prisoners and forced laborers brought to the Soviet Union. The choice of the date was linked to the fact that on this day in 1953, 1,500 political convicts came home from the Soviet Union.

Málenkij robot memorial site next to Ferencvárosi Railway Station/Source/Wikiwand

In Hungary, memorials to the sad historical event were erected in many places (Berkenye, Kazincbarcika, Pécs Szerencs, Taksony, Vállaj, Vásárosnamény, Záhony, etc.). Memorial sites were created in several places beyond the border: the Szolyvai Memorial Park was built near the mass grave of the former concentration camp in Transcarpathia, and a memorial plaque was inaugurated in the Házsongárd cemetery in Cluj.

Source, image and full article: multkor.hu