In recent days, several unreasonably irritated, sometimes rude, young colleagues objected to the fact that I do not analyze, but "only make predictions", writes Robert C. Castel, senior employee of Neokohn, on his Facebook page.

I think there is a reasonable suspicion of a text comprehension deficit here. Sometimes it's good old-fashioned bad faith.

Like all analysts, I had my quibbles. I see further learning opportunities in these mistakes, and it is a fact that my article admitting one of these mistakes and correcting it became one of the most popular.

As for the charge of "prediction", I usually get this from historians who, as gold-crowned researchers of Old Slavic sniping, feel competent to analyze Russian nuclear doctrine.

My response to these charges is not to predict, but to object.

I usually don't try to figure out what will happen, but instead I say what is missing from the picture. What do I base these claims on? On military theory, lessons from case studies, and my own experience.

Interestingly, in many cases the things I missed were realized with some delay. This does not prove my secret qualities, but that the art of war is based on objective principles.

What were the things I missed?

• The Ukrainian recapture of Snake Island as a symbolic victory, without which the reconquest of the lost territories in the east is hopeless.

• The futility of the two-dimensional nature of war and the importance of depth strikes.

• Lack of operational and strategic creativity and innovation.

• Lack of surprise, both operational and technological.

And other.

I have also stated on several occasions that the only hope for victory for the Ukrainians is to master these force-multiplying methods.

The success of the Harkiv counterattack, but also of the depth strikes in Crimea, prove that I was not the only one who perceived these shortcomings.

The Ukrainians and their Anglo-Saxon advisors also dusted off the technical books we grew up on and successfully applied the principles laid down in them.

As far as the Russians are concerned, the Kharkiv lesson contains a series of very important lessons, even if the tuition proved to be very painful.

The recurring lesson of the Arab-Israeli and the two Gulf wars is that the Western operational doctrine is more powerful than the rigid and conservative Soviet-Russian doctrine.

If the Russians want to win, they must learn to fight in the Western way.

And of course risk-taking, flexibility, creativity, innovation, the role of surprise and deception.

The things I've missed since the first day of the war on both sides of the firing line.

These are the ingredients that I diligently miss when I'm not wasting my time debating the professional issues of a 21st century war with researchers of Old Slavic woodcuts.

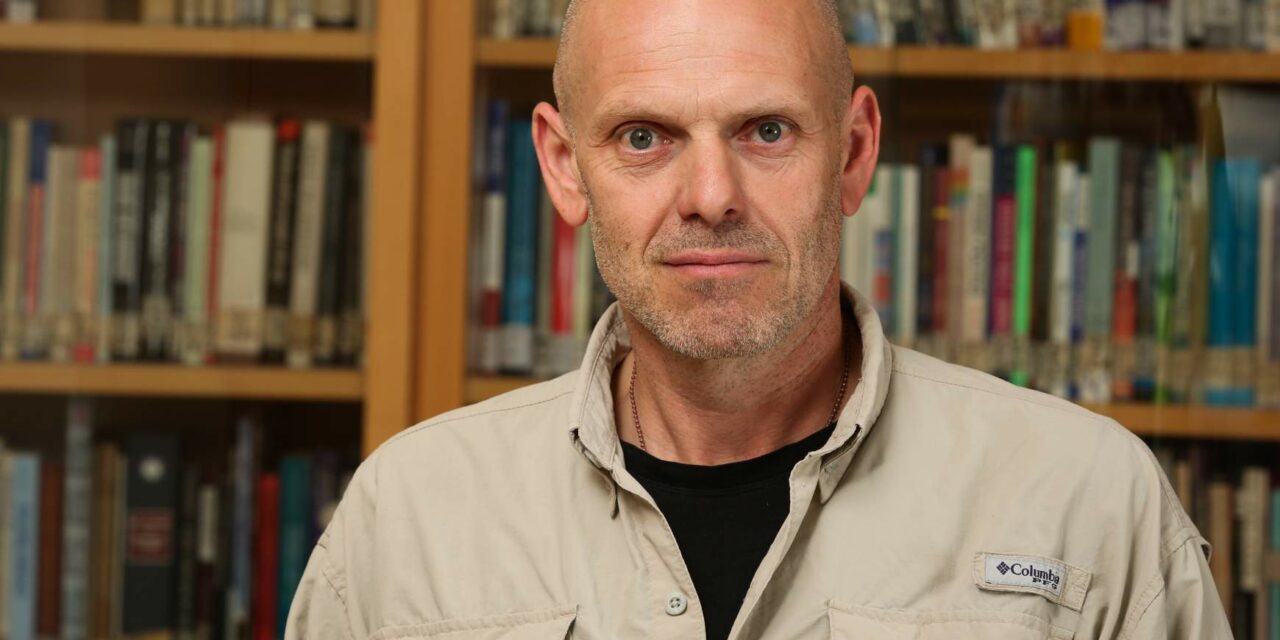

Featured image: Israel Democracy Institute