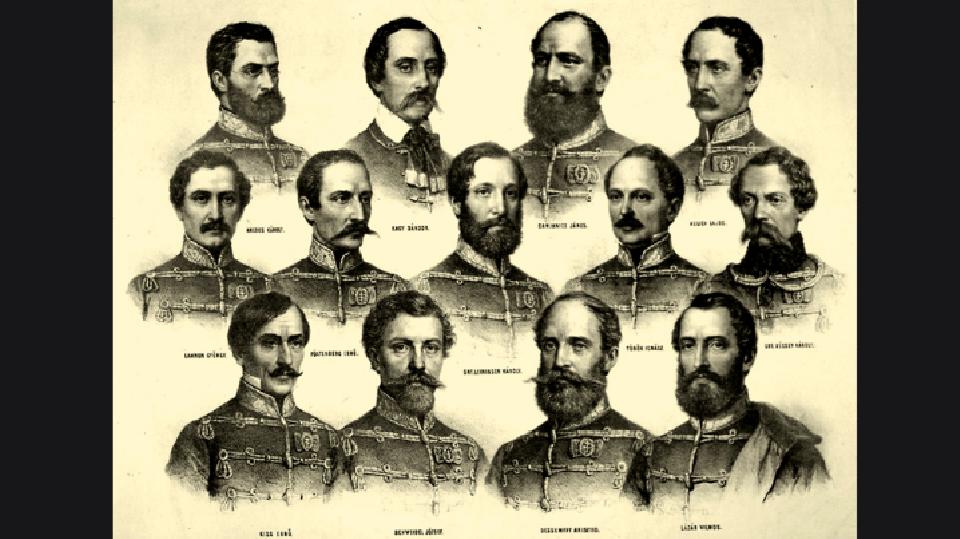

The martyrs of Arad were executed on October 6, 1849, after the fall of the War of Independence, on the first anniversary of the Vienna Revolution and the assassination of the Imperial Minister of War Theodor Baillet von Latour. Since then, we remember October 6 as a day of mourning for the bloodshed of the revolution and freedom struggle.

Although the number of military officers executed on Arad was sixteen, the national memory still primarily counts the thirteen officers executed on this day. The martyrs of Arad were active or retired imperial officers at the beginning of the War of Independence. At the end of the War of Independence, one of them held the rank of lieutenant general, eleven major generals and one colonel in the national army. The Austrians wanted to set an example by retaliating for their role in the 1848-49 War of Independence.

Laying down arms

The Hungarian army laid down its arms in front of the Russian troops on the field in Vlágos near Világos: the nation, despite its desire for freedom, could no longer fight against the armed forces of two great powers. Due to the hurt pride of the Austrians - that the surrender did not happen in front of them - instead of the death by gunpowder and bullets that were due to the generals, death by rope was prescribed for the Hungarian commanders, after the Russians - although they had promised to the contrary - handed over their prisoners. The latter punishment - which was previously only applied to common law citizens - also had a humiliating character.

Charges and convictions

15 of the 30 Hungarian generals fell into the hands of the Allies. Among them, Görgei and Pál Kiss, who was granted amnesty for the surrender of Pétervárad, avoided court-martial proceedings. Two generals, Miklós Gaál and Gusztáv Pikety, came into the hands of the imperial and royal authorities only weeks later.

The idea of retaliating against those who participated in the War of Independence had been preoccupying the Austrian authorities since November 1848. However, the proclamations and decrees issued by the monarch and Field Marshal Alfred zu Windisch-Grätz, the commander-in-chief of the imperial and royal (ch. ex.) army, mainly threatened the Hungarian political leadership, the members of the National Defense Commission and the parliament with severe retorts. Windisch-Grätz served in the Hungarian army cs. out. he regularly called on officers to return to the common flag, the last time in January 1849. However, contemporaries were surprised to find that cs. out. the commander-in-chief released the deputies after a relatively short verification procedure, but the Central Military Investigation Commission in Pest imposed heavy penalties on the soldiers.

Two deadlines were taken into account for the defendants. On the one hand, on October 3, 1848, i.e. the issuance of the royal manifesto which dissolved the Hungarian parliament, classified the actions of Kossuth and his associates as illegal, placed the country under martial law and appointed Jellasics as the all-powerful royal commissioner. The court-martial treated this cut-off date "flexibly": for the officers serving in the South Region, the date from which they were accused of participating in an armed rebellion was calculated from October 10, 1848. (The Temesvár castle guard and general command announced the manifesto of October 3rd on this day.) For those serving in the Danube army, Windisch-Grätz's summons on October 17th and the battle of Schwechat on October 30th were considered as starting dates.

The second date was April 14, 1849, the day of the declaration of Hungarian independence and the abdication of the Habsburg-Lorraine ruling house. Officers who served thereafter could be convicted of treason. The court allowed some "grace time" here as well. András Gáspár, who resigned from the corps command on April 24, 1849 and asked for sick leave, was only convicted of the crime of armed rebellion. However, the judgments were already made before the trial.

The court-martial was headed by the general military judge Karl Ernst, and the verdicts were confirmed by Julius Jacob von Haynau - whom his soldiers only called Einhau (push) - as the all-powerful governor of Hungary. All the generals were sentenced to death by hanging, even though Dessewffy, for example, was promised free retreat before laying down his arms. Based on the recommendation of the court-martial, Haynau commuted his four death sentences from special mercy to death by bullets and gunpowder worthy of officers. Lieutenant General Ernő Kiss received this "grace" because he never actually fought against the imperial forces during the War of Independence. Aristiztid Dessewffy and Vilmos Lázár laid down their arms before the imperial troops, and József Schweidel fought against the imperial forces only in the Battle of Schwechat, he later served in administrative positions, and as the city commander of Pest he had the opportunity to build a good relationship with the Austrian officers who were prisoners of war.

The execution

The pronouncement of judgments, the manner and sequence of executions were based on well-considered considerations. Damjanich caused the most annoyance to the Imperials, so he should have been the last, but Haynau's personal revenge overrode this: Count Károly Vécsey was the last to be executed.

Died by gunpowder and bullets (at half past six in the morning):

Chief Officer Vilmos Lázár

Count Dessewffy General Aristid General

Ernő Kiss General

József Schweidel

12 soldiers stood in front of them with loaded guns, their commander waved his sword and shots were fired. All three, except for Ernő Kiss, fell lifeless to the ground. The shot only hit Ernő Kiss in the shoulder, so three soldiers stood directly in front of him and all three fired again.

Died by rope (after six o'clock in the morning):

General Ernő Pöltenberg General

Ignác Török

General György Lahner General

Károly Knezich

József Nagysándor

Károly Count Leiningen-Westerburg General

Lajos Aulich General

János Damjanich General

Károly Vécsey Count

Károly Vécsey's punishment was aggravated by the fact that he had to watch the execution of his companions, because he was the last to be hanged. The martyred generals said goodbye to each other in a row, Vécsey had no one to say goodbye to, so he approached Damjanich's corpse and kissed Damjanich's hand.

After the execution, the corpses of the condemned were put on public display as a deterrent. On the evening of October 6, the shot dead generals were buried in the ramparts, and the hanged martyrs were buried in the place of loss. Since the clothes of the executed were suitable for the executioner, the bodies of the hanged were stripped and placed at the base of the gallows, and then the gallows' columns were knocked down next to them.

The Russian Czar Nicholas I tried to influence his relative Ferenc József in the direction of clemency, and expressed his displeasure at the executions through diplomacy. The onomasticon created that day in Arad Castle and summarizing the initials of the names of the martyrs: "PANNÓNIA! VERGISS DEINETODTEN NICHT, ALS KLAGER LEBEN SIE!” (Hungary! Remember Your Dead as Accusers Live!)

More Arad martyrs

Between August 1849 and February 1850, three more army officers were executed in Arad: on August 22, 1849, army colonel Norbert Ormai, the commander of the army hunting regiments - he is also called the first martyr of Arad - on October 25, 1849, army colonel Lajos Kazinczy , the son of Ferenc Kazinczy, and on February 19, 1850, Lt. Col. Ludwig Hauk, General Bem's aide-de-camp. National Guard Major General János Lenkey also died in the Arad castle prison, he was not executed because he went insane in prison.

In addition to the Arad martyrs, we have an equally important duty to remember Count Lajos Batthyány , the prime minister of the first independent responsible Hungarian government, who was executed on the same day in Pest in the courtyard of the former Neugebäude building, today's Szabadság Square.

And this fate also befell another 20 high-ranking military officers. Hundreds of military officers were also sentenced to death, but most of the sentences were commuted to twenty years in prison. Thus, the prisons of the empire - the Újépulet in Pest, Olmütz, Josefstadt, Kufstein, Theresienstadt, Munkács, Arad - were filled with Hungarian political prisoners.

Many of those who fled abroad were sentenced in absentia and put their names on the gallows for public viewing. In September 1851, Lajos Kossuth, Lázár Mészáros, Mór Perczel and Miklós, Bertalan Szemere, Gyula Andrássy and Mihály Táncsics were hanged in this way. Finally, tens of thousands of military officers were conscripted into the imperial army as privates for years.

However, the freedom struggle was not a futile struggle: the conditions before the revolution could no longer be restored and despite the fall, the idea of freedom and independence not only continued to live in the nation, but also continued to strengthen. And the country, although at the cost of huge blood sacrifices and deprived of national self-determination, started on the path of civil development.

Until 1867, commemoration of the Arad martyrs could only take place in secret, but after the agreement, October 6 became a national day of mourning. From October 6, 1890, the audience in Pest could hear Lajos Kossuth's commemorative speech about the heroes of Arad from the Edison phonograph cylinder set up in the first-floor hall of the Vigado:

"The judge of the world, history will answer this question. May the martyrs of the holy memorial be blessed in their dust and in their spirits with the best blessings of the God of freedom through eternal reality; I cannot fall down in the dust of the Hungarian Golgotha, October 6ka will see me on my knees in the hermitage of my statelessness, stretching out my arms towards the Homeland that has denied me and I bless the holy memory of the martyrs for their loyalty to the Homeland, for their lofty example, which is given to the descendants; and with fervent prayer I ask the God of the Hungarians to make triumphant the heart-felt words that ring out from the lips of Hungária to the Hungarian nation. So be it. Amen!"

Lajos Kossuth, Turin, September 20, 1890.