There are a lot of Russians compared to Ukrainian human resources, and no amount of lust-driven navel-gazing can change that fact . Note by Robert C. Castel.

A few days ago, Világgazdaság, quoting the Institute for the Study of War, reported that "The theory that "there are as many as the Russians", Moscow can hardly find men for the war, seems to be overturned".

the publications of the above-mentioned well-known think tank that , in addition to the announced three hundred thousand reservists, the Russians called up another two hundred thousand people through silent mobilization. The source was the Ukrainian Minister of War, the official for whom there is little more important data in this white world than the manpower available to the adversary.

Of course, it is also possible that, like all other components of the war, data related to Russian manpower will be covered by the fog of the battlefield, condemning us to a state of eternal uncertainty. Furthermore, it is also possible that these statements can be considered more like estimates, perhaps chess moves of information warfare, than empirically proven data.

Be that as it may or not, until the ISW analysts decide in-house that there are too many or too few Russians, it is worthwhile to look at the known and indisputable data and draw conclusions from them.There are very close connections between demography and warfare. These relationships work both ways. Throughout history, larger populations have generally meant greater military power, and the use of military power has on many occasions dramatically affected the demographics of warring parties. At the same time, it would be a mistake to assume simple, linear relationships between the two variables. Certain forms of warfare, such as conventional warfare and counterinsurgency, are traditionally human-intensive enterprises. At the same time, other forms of combat, e.g. thermonuclear war or cyberwarfare, they turn on the quality of manpower rather than the quantity.

In the context of the Ukrainian war, most analyzes look at the demographics of the two opposing countries as a whole. Some of these analyzes are content to point to a static Russian demographic advantage of one in three before the war. Much more useful are the analyzes that take into account the demographic changes caused by the war, the population of the annexed territories, the refugees of the war and the economic emigrants who left before the war. These analyzes speak of numbers that are even more unfavorable than the previous one, approaching a ratio of one to four.

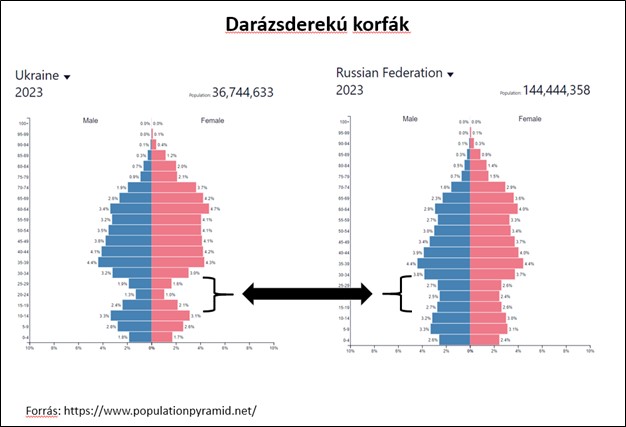

The biggest weakness of these analyzes is that the subject of the investigation is treated as a unified whole, even though from a military point of view it does not matter whether there are many grandmothers or young men, whether the crown of a state is a cypress tree or an umbrella acacia.Those who are less familiar with these graphs should take a look at the illustration of the Russian and Ukrainian Korfa.

To interpret the graphs, it is enough to be aware that the "year rings" of the age groups represent age groups in five-year bands. The blue color shows the percentage of the male population in a given age group, and the pink shows the percentage of the female population. For this choice of color that perpetuates patriarchal oppression, demographers will one day get theirs, but every profession has its own dangers.

To put it seriously, it is obvious at first sight that both korfas have a bit of a wasp waist, and that the Ukrainian "umbrella acacia" is much slimmer in waist than the Russian "cypress tree".

And this is where things get interesting.

Because, due to history's peculiar quirk, the hornet's waist includes precisely those age groups in the case of both states that bear the burden of this war. That is, the male population from the age of 15 to 44, divided into six age groups. As for the percentages listed next to the age groups, it would be a mistake to hastily compare them, since the percentages were not created equal. 2.4% of Ukraine's nominally 36 million population is a completely different category than 2.7% of Russia's 144 million population. We can only really understand the degree of asymmetry if we compare absolute figures instead of percentages.

The male population of the first age group, between the ages of 15 and 19, is 0.8 million in the case of Ukraine, but 3.9 million in the case of Russia.

In the case of the second age group, between 20 and 24, this ratio is 0.4 million, compared to 3.6 million. In this most critical age group, this means a nine-fold Russian overpower.

The third age group, the band between 25 and 29 years old, lists 0.6 million Ukrainians compared to 3.8 million Russians.

In the case of the fourth age group, the "year ring" between 30 and 34, this ratio is 1.1 million compared to 5.5 million.

For the fifth age group, 35 to 39 years old, this ratio is 1.3 million compared to 6.3 million.

And the sixth "year ring", in the age range from 40 to 44, lists 1.5 million Ukrainians against 5.5 million Russians.

Regarding the manpower reserve, the real ratio is not 1 to 3, or perhaps 1 to 4, as other analysts claim, but rather 1 to 6 for the two youngest age groups that are really relevant, the 20 and And for the age group between 24 years, the ratio is 1 to 9.

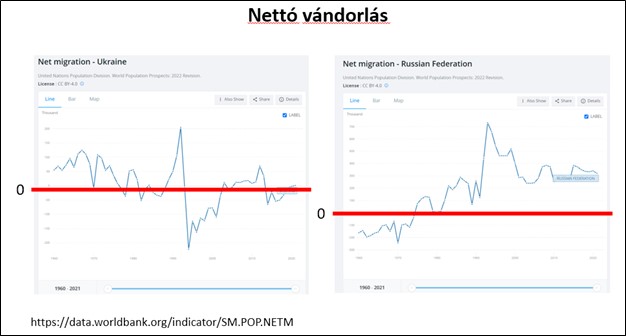

However, that is not all. Another very important aspect of military demography is the question of immigration. Many wars in history, including the American Civil War and Israel's War of Independence, were decisively influenced by so-called "net migration" indicators.

What is "net migration"? The number we get when we subtract the number of emigrants from the number of immigrants.

If we compare the two states at the level of long-term trends, we see to our considerable surprise that Ukraine is an emigrant state, while Russia is clearly an immigrant state.

Of course, all this is not a coincidence, but the result of consistent Russian immigration policy. I can almost hear the clinking of broken hearts on both sides of the ideological fire line when I describe that Russia's immigration policies are among the most liberal in the world. To obtain citizenship, it is enough to stay in Russia for five years and cough up a Russian language test. You can obtain an almost immediate and unlimited residence permit through employment. Under certain conditions, these processes can be shortened to three years. In addition to all of this, the Russian state acted in a draconian manner against anti-immigration political organizations, such as the DPNI movement, which broke away from the ultra-nationalist Pamyat and was organized by Aleksandr Potkin.

One can like or dislike Russia's immigration policy, but one thing is undeniable. The fact that it is based on a well-thought-out and implemented national strategy.

As for the pots, the bin is next to the exit door.

Of course, all this does not mean that victory is guaranteed for Russia.Military history knows countless examples in which, contrary to the well-known cliché, God was on the side of the smaller battalions. It is also necessary to be aware that, in accordance with the Napoleonic dictum repeated to the point of boredom, the moral in war is related to the physical as three to one. A war of national defense undoubtedly has a stronger motivating force than one whose real goals are not fully understood by the soldiers.

These are compelling arguments, but not bulletproof.

In order for God to actually side with the smaller battalions, some kind of quality multiplier is needed to offset the quantity superiority.My view is that as the war in Ukraine drags on, it is precisely this superiority in quality that wears out more and more, since those formations that were the most experienced and best trained and carried the first year of the war on their shoulders were the most depreciated. The fate of the very significant fighting value but relatively small British army with which Albion entered the war in 1914 was similar. The British contingent, described by the Kaiser as a "despicable army", fought heroically to give the island nation time to switch to mass warfare. However, the price paid by the "old bastards" was hellish. By the end of the war, statistically speaking, the entire British Expeditionary Force of 1914 was lost.

As for the moral factor, those who felt this war was a matter of their heart and volunteered to go to war, probably did not wait a whole year for the adventure of their lives and have been fighting on the front for a long time, or else they became victims of the war. Seeing the Russian and Ukrainian conscription difficulties, it can be said with great certainty that the time for enthusiasm is over, and very few soldiers would go to the front of their own accord. What remains is the coercive power of the Hobbesian Leviathan, which is rushing towards total war.

So how many Russians are there in the end?

Compared to the human resources of Ukraine, they are depressingly many, and no desire-driven navel-gazing can change this fact.It is also important to realize that this problem is not only a problem for Ukraine, but for the whole of Europe. And in the long war that awaits us in the 20s and 30s of this century, demographics will be at least as decisive as technology.

It is not too late to start thinking about our demography in a geopolitical context, if we do not want to repeat the big strategic mistake we made in the energy policy of the last decades.Featured image: EPA/YURI KOCHETKOV