Apart from the circles of music and religious historians, perhaps few people know the name of György Náray, even though he kept the spirit of the faithful in one of the most difficult periods of Hungarian history and served in many parishes. Meanwhile, he even had time to acquire, collect and write down Christian songs.

Literary and spiritual historian Vera Szádoczki, who has been researching the life of the special polymath for years, points out: György Náray's work is not unknown in the literature, Emil Békési wrote an exhaustively thorough series of studies about him in Magyar Sion at the end of the 19th century, while Ferenc Sill appeared in the columns of Vigília articles about his life and Chronicle. We can also meet him in the music history volumes and studies of Mihály Bogisich. His melodies were recorded and examined by Géza Papp in his volume on the Old Hungarian Melodies Collection.

However, his name is not only found in these studies: anyone who opens the Hosanna, a Catholic hymnbook still in use today, can discover that Náray is the author of many Christian songs that are still sung today, for example, O blessed saint Istenem. He composed the melody for several songs, such as the song of the Way of the Cross: Our hearts, our souls are now opened... or his melody is the heart of Jesus, the purest heart...

Musical training in Rome

Vera Szádoczki's responsibilities include arranging a volume from the 17th-century series of the Old Hungarian Poets Library for publication in the Baroque Literature and Spirituality Research Group. He is therefore thoroughly familiar with the life of György Náray, who was born on April 23, 1645 in Pálóz, Zala county. He began his schooling at the Jesuits in Nagyszombat ten years later, completed the first two classes here, then finished high school in Győr, from where he returned to Nagyszombat and started university, with the intention of becoming a priest. He also studied music.

Vera Szádoczki is a historian of literature and spirituality

In May 1666, on the recommendation of the rector of the Nagyszombat college, the Archbishop of Esztergom sent him to study at the Collegium Germanicum Hungaricum in Rome, from where he returned home as an ordained priest after two and a half years. These narrow three years are decisive in the further development of his life path. Despite the fact that instead of the usual 4-5 years, Náray spent only three in the eternal city.

When the 21-year-old Náray arrived in Rome, the international colleges were under dual management. On the one hand, they functioned as papal seminaries, and on the other hand, the Pope entrusted the management of the institutions to the Jesuits. This means that the theological subjects were studied together by the alumni at the Collegio Romano according to Ratio studiorum This meant scholastic theology (dogmatics) on the one hand, and practical theology (morality, church law, polemical theology) on the other.

Náray lived in the Collegium Germanicum Hungaricum, where spiritual education played a major role. The spiritual leader of the institution is the spiritualist, who was also the confessor of the alumni. This office was held for a long time in the middle of the 17th century - even at the time when Náray was there - by János Nádasi, who was considered one of the most prolific writers of the time with his ascetic and devotional works. These works played a major role in the formation of the spiritual mentality of the alumni: instead of the military, debating spirit, they conveyed the baroque ideal of piety. This probably had a significant influence on Náray.

As well as the fact that the students received thorough musical training at the institution. The high-quality, high-level musical training is especially valid for the half century when Giacomo Charissimi held the post of organist (1629–1674), i.e. when Náray was there. The superiors sometimes had to speak out against the exaggerated singing cult, as the constant singing rehearsals interfered with learning and rest.

This musical environment and what he learned there certainly influenced Náray, who was already well versed in music, they could shape his musical taste, shape and deepen his existing knowledge, he could come across melodies and texts that he then translated or reshaped into his own singer's book. He certainly came across several lyrics there and later translated them into Hungarian.

The fact that the influence of this musical training did not remain is better proven by the fact that he was an alumnus of the Collegium Germanicum Hungaricum, and that this musical thinking was brought home by the later bishops of Eger, Benedek Kisdi and Ferenc Lénárd Szegedy. Cantus catholici of 1651 played a role in the publication of Cantus catholici of 1674

The musician priest went from parish to parish

As indicated above, Náray left the eternal city at the end of 1668 and returned home. But where? We could rightly think that he would return to his homeland, the diocese of Zagreb or Esztergom, but that was not the case. In 1669, in the shadow of the Turkish destruction, it was transferred to Mátraszőlős. According to Ferenc Sill, we might not be wrong if we look for the reason for this in Náray's missionary intentions. The Hungarian theologians studying in Rome must have been informed that the Holy See constantly urged the provision of pastors to the territories under Turkish vassalage. Many such requests came to the popes from the Catholic faithful living in the diaspora, who did not fail to draw the attention of the Hungarian bishops to send ordained priests to the subject areas.

It is not known why Náray ended up in Mátraszőlős. However, it is a fact that the diocese of Váci, which was occupied by the Turks, was in great need of priests around this time, and Mátraszőlős belonged to this county.

The Historia Domus writes that the church was renovated in 1669 during Náray's parish. He brought the altar of St. Elizabeth of the Franciscan church from Szécsény, which was ravaged by the Turks. This was revealed in the contemporaneous minutes of the Saint Nicholas and Immaculate Conception Societies, which he also founded. This protocol dates from the early 1700s, when there were still people who remembered Náray. Since then, unfortunately, the protocol has disappeared, only the Historia Domus testifies to the former existence of an entry. Náray also renovated the side altars, such as the altar of the Immaculate Conception, on which a contemporary Latin poem can be read. Maybe Náray wrote it?

The following year, in 1670, we find it in Jászó. During this period, quite chaotic conditions prevailed in the diocese of Eger. Eger was in Turkish hands, the bishopric and the chapter fled to Kassa, and from there to Jászó, and then back to Kassa, but the bishops of Eger did not completely give up Jászó either. The superior of Eger at this time was the previously mentioned Ferenc Lénárd Szegedy, who became the bishop of the dioceses in the subjugation (periphery) areas.

We need the native language songbook!

With the end of the era of religious debates, another trend gained strength: the emphasis on the close relationship between the lyrics and theological content, music and faith. Vera Szádoczki highlights: music was made a tool of re-Catholicization and Catholic renewal. Náray certainly already started collecting for his future songbook during his years in Mátraszőlős and Jászó. He had the qualifications for it and there was also a desire in the air to compile hymnals, with which they could put hymns with appropriate theological content into the hands of the people in their native language.

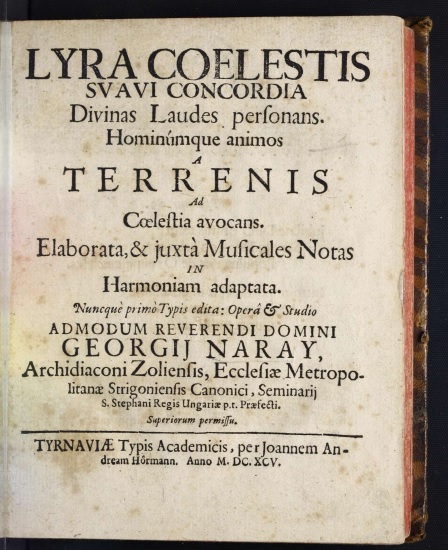

Lyra coelestis

That he could have been thinking about some kind of collection of singers even then, nothing proves it better than the Vesperas text published as an appendix to Lyra coelestis

Around 1671, he was the parish priest of Pétervásara, and two years later he served in Egyházasbást in Gömör county, which already belongs to the diocese of Esztergom, and he remained in the service of this diocese until the end of his life, rising higher and higher in the ecclesiastical ranks. In 1674, he became the parish priest of the market town of Csallóköz. Two of his manuscripts from this time have survived, one is a chronicle, in which Náray began to record the market town's customs, liturgical order, church singing and schola organization, and his successor continued this. This document has been in the Thursday parish ever since. A collection of sermon sketches by the other.

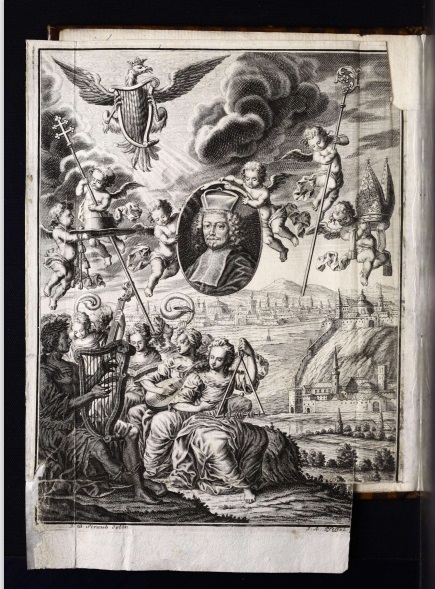

In 1679 he became an episcopal vicar, in 1684 a Bratislava canon, and two years later he also held the position of dean of the chapter. For two years, in 1685 and 1689, he was the rector of the Emericanum, and then in 1690 he was a canon of Esztergom. From the following year, he became archdeacon of Zólyom, and held these positions until his death in 1699.

In the last decade of his life, three of his works were published. His latest and best-known songbook is the already mentioned Lyra coelestis from 1695, with 167 Latin and Hungarian songs, about a hundred of which he composed himself. Two more of his booklets that help and encourage practical religious life have been published. The Bratislava University Library currently holds a single, truncated copy of the 1693 A Szentháromság olásójárul The Hungarian-language volume teaches to pray in order to give the people a spiritual weapon in the troubled times. In it, Náray explains a type of rosary. He compiled the other form for priests, in Latin. The purpose of this is to set an example for those in the service of the church, how to grow in their spiritual life and organize their parish in a more practical way.

Currently, we know of a total of 22 volumes in which Náray's name is mentioned in some form, i.e. it was his book, and these are kept in Esztergom today. "The staff of the Bibliotheca in Esztergom have not yet finished processing the entire book collection, it is conceivable that, as the work progresses, more books from Náray's library will be found," hopes Vera Szádoczki.

The mentioned 22 volumes contain a total of 26 works. Their linguistic composition is interesting: there are 8 Latin and 18 Italian forms. We could rightly think that he acquired the Italian volumes during his stay in Rome, and for some of them this is indeed true, but there are volumes that were published after Náray returned home from Rome. Five publications from Venice, one from Turin and one from Padua. Also, the volume in which he wrote in 1671 that he was a parish priest in Pétervásár was published in 1663.

To cultivate, at all costs!

In any case, the fact is that even after his return from Italy, he sought to acquire books during the turbulent Turkish subjugation - from Italy. There is no source on whether he managed this through personal connections or through official means. It is striking that there are no works in Hungarian among his books, nor by Hungarian authors.

Of course, we find some of the books that contain songs, such as Il Christo caritativo , which publishes Italian and Latin songs and litanies. The thick Rosa Boemica deals with the life and work of St. Adalbert. The book, decorated with numerous engravings, consists of two parts, between the two sections, on a fold-out sheet, the Canticum Sancti Adalberti (Song of St. Albert) is bound in Czech and Latin. Several other songs and hymns addressed to Adalbert in Latin and Czech were also included in the volume, some of which also have their sheet music.

Lyra coelestis

And finally, but not least, it is worth mentioning Joannes Bona's work published in Cologne in 1677, De divina psalmodia , highlights Vera Szádoczki. It is not a hymn book, but on its almost 800 pages it records the theoretical knowledge that can be known about singing, psalms, the place and role of music in the liturgy. And the highlights show that Náray filmed this volume.

What else did Náray use these volumes for? For example, the Della dignita , with its quarter-fold size, is considered large in the examined book material, several blank pages were bound at the beginning and end of the book, which could have been filled with great writing, and this is exactly what Náray did. Over six pages. On the front pages before the title page, he inscribes a Hungarian poem, probably his own composition:

Terrible weddings are terrible secrets

I drink sin like water after every word you say

You roar like angry lions.

Your angry hearts thirst for blood

You're just a bunch of robbers and robbers

Where did evil lead you to despair.

Annotationes with a poem - in Latin, of course . "Sometimes I got the feeling that if Náray saw a blank page, he compulsively scribbled a poem on it," says Vera Szádoczki, adding that these entries are valuable documents from the point of view of poetry technique and writer's methodology, as well as the process of the poem's birth.

In many cases, Náray composed the melody of his songs himself. To our question whether it is still expected that a volume of the early modern musician-priest's books will be found, the literary historian responds: even if it still happens, there is a chance for it in Esztergom. "But I'm not sure if it's worth searching at his former stations, since some of these settlements now belong to Slovakia, and the library system there doesn't deal with ownership entries in books at all, so it's relatively difficult to search and the result is completely contingent. Can we find any other material from him? There is hope for this, because I have not yet examined the material of the Esztergom archive. Furthermore, according to his biography and source publications written at the end of the 19th century, letters from him were kept in the Nagyszombat archives. I don't know what happened to them. Rome would definitely be worth a try, where Náray certainly sent letters, as evidenced by the draft of a letter bound in his diary," points out Vera Szádoczki.

Author: Tamás Császár

Cover image: Illustration / Pixabay