Was Count István Széchenyi of Sárvárfelsővidéki, whom even his political opponent, Lajos Kossuth, called the greatest Hungarian, a victim of murder or suicide?

According to the officially accepted position, he committed suicide, but due to the suspicious circumstances and the danger he posed to the Viennese court, many still believe with conviction: Széchenyi was executed by the emperor. The conspiracy theory behind the exciting story was revealed by historian László Csorba, doctor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and director general of the Budapest History Museum at the event of the Academy of Our Age on April 19.

Count István Széchenyi of Sárvárfelsővidéki was born in 1791 in Vienna. The statesman was a privy councillor, imperial and royal chamberlain, writer, polymath and economist. Through his ideas and political activity, he significantly contributes to the creation of "modern Hungary". He introduced reforms in the fields of sports, transport, the economy and foreign policy, and created a forum for intellectual men who wanted to do something. The foundation of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the Hungarian Society of Scientists, is also attributed to him. Although he was an active player in political life, he held completely opposite ideas to another influential public figure of the time, Lajos Kossuth. When the revolution broke out, everyone sided with the latter, and Széchenyi was unable to cope with the difference between what he considered to be correct and the real political arrangements. He was tormented by the vision of the death of the nation, oppressive self-blame and remorse that he could not save his people.

Széchenyi withdrew from social life, developed strange behavior patterns, did not go out the door, did not talk to anyone, and stopped writing. In September 1848, everyone knew that he was sick, so he was taken to Görgen Hospital in Döbling.

He spent many years here, and his condition suddenly began to improve. Around 1850, he slowly picked up a pen again and began to correspond with his friends. During these years, he also received visitors, so he started to live a social life again. Although he did not leave the building, he became interested again in his old favorite activities, games, the world and people. His acquaintances, seeing him for the first time in a long time, seriously questioned his alleged illness. Ferenc Deák wrote about him: "his mind is just as it was before, his performance is just as interesting". Whatever was tormenting him on the inside, he was able to present himself perfectly on the outside, and aside from the abnormal behavior patterns, it was hard to believe that this man had ever been seriously ill.

In 1856, he started to write voluminous texts again, at first only thoughts about self-knowledge, but in 1857 he got his hands on an article about the exaltation of the Bach system, the key idea of which was that the Austrians are the ones thanks to whom the barbaric Hungarians will become civilized.

This offended him so much that the subject of his own texts changed radically. He has now written long, voluminous letters and essays about how disgusting the new Austria is. These works were characterized by strong satire and obscenity, and fundamentally mocked the emperor's system. He sent his son Béla Széchenyi to England, where through their connections they arranged the secret printing of these texts, and his writings even appeared in the columns of The Times, which was openly pro-Austrian. Thanks to this, even the Western press urged reconciliation with the Hungarians. Béla Széchenyi's lover, Lady Anne, was still with her III. He also conveyed old Széchenyi's ideas to Napoleon.

When he already had a great reputation in England, new writings began to be published at the Döbling institute. Széchenyi was visited by many of his friends, and together with them he started a "secret activity", i.e. they wrote anonymous pamphlets mocking the system and began to distribute them in the domestic and foreign press. After a while, the Viennese court became suspicious of the secret "press center" and on March 6, 1860, they attacked the Széchenyis. They confiscated his writings and announced that he could no longer stay at the institute.

On April 1, he wrote his last diary entry: "kann mich nicht retten", meaning "I cannot save myself". In the early hours of April 8, a serious head shot took his life.

The whole country mourned. In his poem, János Arany called Széchenyi's death "the moments of deification", which clearly shows how much of a cult has built up around him over the years. The people received a new impetus, since the death of the hero always gives strength to continue the fight. In the official reports, suicide was established as the cause of death, but the rumor quickly began to spread among the mourning people. Everyone knew what a critic of the system Széchenyi was, and that he voiced his opinion, thereby endangering the emperor's authority. In any case, the basis of the thinking of the time was that the worst possible thing could be imagined about Vienna, so the people's opinion was no other than that the Austrians had killed the Hungarian messiah.

However, is there a basis for these assumptions?

Source: Rubicon

Historian László Csorba drew the attention of the audience so that we don't forget: the logic of the conteo is exactly the same as that of the criminal investigation. The first question that is asked in this case is whose interest was in the person's death. After that, it is necessary to establish whether an accident, murder or suicide occurred. The first possibility quickly becomes clear, but if it is ruled out, the production of conspiracy theories can "start".

Széchenyi's death was indeed in the interest of the Viennese court. Conteo believers have come up with countless arguments to the effect that suicide is completely out of the question.

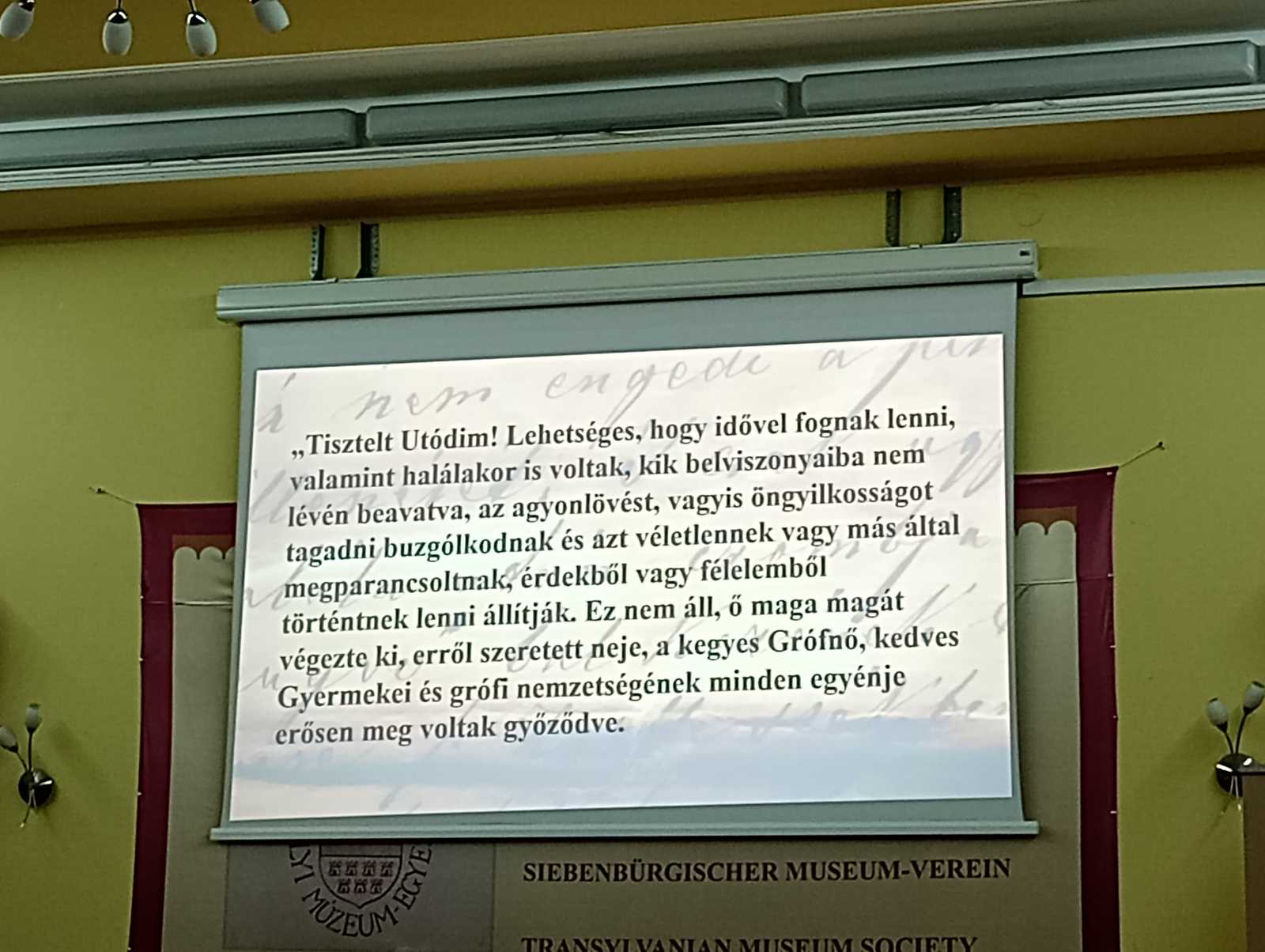

First of all, they believe that Széchenyi was not mentally ill, he just had a nervous breakdown. Furthermore, he was a committed Catholic man who would never have done such a thing, if only because the church would not have buried him. Many people also think the position of the body, as they found it at that tragic dawn, is suspicious. In the report of the crime scene investigation committee of the criminal court, it can be read that "his two hands rested on his thighs, his elbows on the arm of the chair. The murderous tool lay askew on the thigh and left hand. The left side of his head was completely destroyed, the wall of the skull lay four or five feet on the ground, and the splattered brain was on the walls and ceiling.

They found cotton strangulation as ammunition, and several birdshot scattered in the brain." Some believe that the body was set up, as it seemed too "organized".

"It is clear from the Fennebis that the murderous shot hit the skull from the left side, according to which Széchenyi, who was not left-handed (left-handed - ed.), would have used his left hand to commit suicide. However, this can be considered out of the question for a person who does not want to be tortured. The left hand is an unreliable and clumsy servant for this purpose, and if the count wanted to kill himself, he would definitely choose the well-practiced right hand"

- can be read in György Kacziány's analysis, which he prepared based on the on-site description. For many, it was therefore suspicious that Széchenyi, who once really fell into severe depression, but recently showed himself to be enthusiastic again, would have ended his life with his unpracticed left hand.

Source: Maszol/Dóra Forró-Erős

So what is the truth? Did Széchenyi really take his own life, or did the Viennese court, which he criticized so badly, order his death? Not only were there doubters in his time, many still believe that he was the victim of the biggest Hungarian murder. According to historian László Csorba, the evidence shows otherwise. The analysts of the on-site report successively omit the fact that traces of black gunpowder were found on Széchenyi's left hand, which could hardly have gotten there otherwise if he had not fired a weapon with that hand. In addition, his acquaintance, Antal Tolnay, wrote in his notebook unearthed in 1958 that the count had previously told him about what he considered to be the purest form of suicide, and that what he said was exactly the same as what was carried out. Even then, many people believed in the conspiracy theory, only the family did not. Even today, many people believe it, except the experts on the subject, the historians. The beauty of the past is that you can never say anything with complete certainty, but knowing the facts, the experts are convinced: despite all the suspicious connections, Széchenyi really killed himself. This is also proven by the complete indignation of the Viennese court at the time: they wanted to condemn the count in court in order to set an example, they were not in the least happy about his death.

The modern age also provided an explanation for his suspicious illness. István Gróf Széchenyi probably suffered from bipolar disorder, the symptoms of which were already evident among his ancestors. This explains the alternation of manic and depressive periods, the "inexplicable recovery" and then relapse. The most serious consequence of the latter is suicide even today.

Featured image source: pestbuda.hu