We leave the myth of the invincible guerrilla to the agitators and comic writers! - Robert C. Castel's answer to Ferenc Kaiser.

Kaiser Ferenc's article published in Mandiner - Expert: Israel has already partially lost this war - is a very remarkable read, mainly because the article is an interesting mixture of correct insights and surprising mistakes. Since the author does not have a subject-specific background in relation to the conflicts in the Middle East, it makes no sense to hold him accountable for his findings.

Regarding wars against non-state actors as a general phenomenon, the article contains some statements that are worth debating, considering that we hear them very often from security policy experts, politicians and media personalities. The problem with these commenters isn't that they don't know anything about the subject,

but the fact that they know a lot about it, they just don't know it well.

Kaiser's article joins the chorus of doomsayers mentioned above with the following statement:

"A guerrilla war is very difficult, if not impossible, to win. A guerrilla army cannot be destroyed, because in many cases the guerrilla army is the people themselves".

The first problem with this statement is that being a people does not exempt you from losing wars. Ever since war became the passion of peoples and nations from the sport of kings, wars have been won by peoples and lost by peoples. This is a very banal statement, which is why it is easy to lose sight of it.

A second intuitive note is that if a guerrilla army or a terrorist organization cannot be destroyed,

then why do the states that make up the international system take the trouble to build armies at huge cost?

This is especially true for those states that prefer to employ guerrilla and terrorist organizations and thereby take on the moral and legal burdens that come with it. Why the hell does Iran maintain an army of hundreds of thousands and, in parallel, a Revolutionary Guard of hundreds of thousands, if it could solve everything more easily and cheaply with the help of guerrilla and terrorist proxies at its disposal?

The answer to this security policy paradox is that those who do not analyze guerrilla warfare and terrorism, but practice it as a profession, are fully aware that it is a weapon of the weak.

Fighting methods that are dictated by desperation have low military efficiency and a very high price must be paid for them.

The experiential wisdom of the practitioners is clearly supported by the literature dealing with the topic. Since the line of demarcation between guerrilla warfare and terrorism cannot always be defined with great precision, it is worth examining the success rate of both categories.

In the field of guerilla warfare, 442 case studies examined by Max Boot on behalf of the Council for Foreign Relations reveal the following: 304 wars (68%) were won by the incumbent state power, 96 wars (21%) were won by the guerrillas, and the rest ended in a draw.

The length of the conflicts did not significantly change the basic pattern either. The only positive thing that can be written in favor of the guerrillas is that during the decolonization process after the Second World War, their success rate almost doubled from 20% to 39%.

Terrorism, as a means of achieving political goals, is far behind in effectiveness even behind guerrilla warfare. the 450 case studies analyzed by Professor Audrey Kurth Cronin, only 20 cases (4.4%) ended with the victory of the terrorist organization. Another 38 cases (8.4%) ended with partial success. The remaining 392 cases (87.1%) ended with the victory of the incumbent state power.

The inherently low military effectiveness of guerrilla warfare and terrorism

it is supported not only by hundreds of years of historical experience recorded in the data series, not only by peasant common sense, but also by military theory.

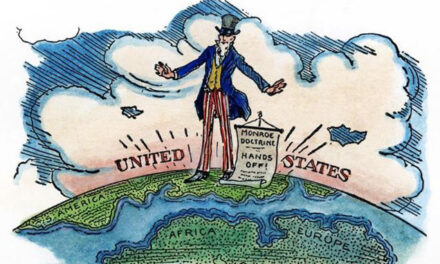

According to Clausewitz's well-known dictum, defense is considered the stronger form of combat, since the compulsion to act falls primarily on the attacker seeking to change the status quo. Since the political goals of guerilla and terrorist organizations in the vast majority of cases are aimed at changing an existing status quo, the course is also strongly tilted to their disadvantage at the level of the theory of war.

One can argue about the long-term political effects of the current Hamas-Israel war, but the military balance of the war fits perfectly into the historical pattern I have outlined.

We will leave the myth of the invincible terrorist or guerrilla to the agitators and comic book authors.

Featured Image: Yoav Nir