"I WANTED TO GO HOME, FINALLY GET HOME"

"I wanted to go home, get home finally,

as he also came in the Bible.

A terrifying shadow in the yard.

Worried silence, old parents in the house.

And they are already coming, they are already calling, poor people

they are already crying, stumbling and hugging each other.

The ancient order welcomes you back.

I reach out to the windy stars…”

(János Pilinszky: Apocrypha)

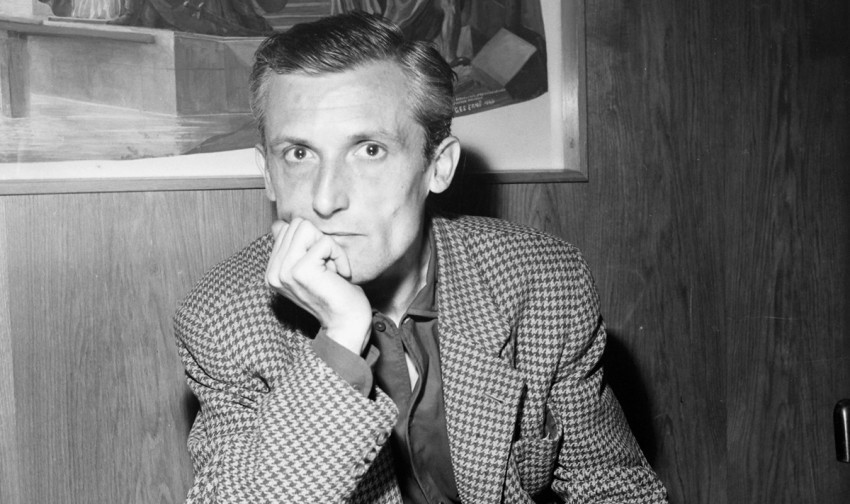

One hundred years ago, on November 27, 1921, in Budapest, János Pilinszky was born, one of the most significant poets of the 20th century, who has not been with us for forty years now, but whose life work gained more and more universal validity over the past decades, has become closer and closer to us: it is hard to find today a more current poet and thinker than him. The picture he draws of human existence in his writings is more and more similar to our current situation, his desires, emotions, and experiences are more and more similar to our emotions, desires, and experiences today. János Pilinszky belonged to the generation of the 20th century who was born directly after the First World War and had to grow up in the great catastrophe of the Second World War.

In an interview in London in 1967, the scholarly essayist and public writer László Cs. Szabó asked him:

"- What kind of memories do you live with?" "With the memory of all of us, the memory of the last war. came the answer. "I think something extremely important happened here." At the same time, we felt, we could feel, that we left an irreparable scandal behind us, which, even if the most beautiful future was ahead of us, even the most beautiful future would become a moral desert if we did not feel responsible for what had already happened."

This personal responsibility makes Pilinszky's poetry more modern and indispensable. His worldview was often called gloomy, even pessimistic, because he did not see the worldwide crimes, wars, occupations, mass murders, genocides that occurred in the 20th century, which was said to be modern, scientific, and enlightened, as a forgettable, accidental derailment, to which the advanced technology of the modern age, its unprecedented achievements, with its mobility, vigorous mass production and trade, and overwhelming consciousness industry, it is not necessary to pay too much attention.

In the last year of the war, he himself gained his defining experiences of human existence and vulnerability as a conscript. The horror of the war was the decisive experience of his youth, he had to experience the immeasurable suffering caused by the lack of peace, greed, irresponsibility and the madness of power, which led to the death of millions of our anonymous comrades. These experiences shaped his emerging image of human existence, his concept of existence. When László Cs. Szabó asks whether the weight of collective guilt still oppresses him decades after the end of the war, his answer is clear: "even today and for two thousand years, Christian art has not taken its eyes off the suffering of Christ..."

When asked if he considers himself a Christian poet, he answers with a thoughtful statement: "I would say that I am not a Christian poet, but I would like to be a Christian poet. This is one of the most difficult things in the world..." János Pilinszky admits this in August 1967, at a time when the ruling, self-proclaimed progressive intelligentsia considered Christianity a harmful ideology, a relic of the ignorant and backward past. This gentle but brave voice, free from the clichés and modern prejudices of the era, and a confessional stance, defines the perspective of János Pilinszky's poetry. In his poems, prose, and essays, almost all of our present-day questions, doubts and concerns about the present and future are heard. But, as we read in his cited poem Apocrypha, he also paints the picture of a man who finds his way back to universality, who is "Received by the ancient order", who sees everything around him, "stretches his elbows to the windy stars."

KATALIN MEZEY