Let's see what happened in the world of media.

As an introduction, it is worth pointing out that in the era of modern, 21st century democracies, the balance of media relations plays a particularly important role, since the majority of political actions and political competition take place within the framework of the media and the press, and voters - as spectators and supporters - pay close attention to they accompany the events and try to judge who is more authentic and convincing. The media and the press are the means through which some topics, issues, cases and scandals become real public issues, and the media are the means through which some important topics are relegated to the background, become non-existent.

A German political scientist, R. Kepplinger, wrote that whoever does not win the political competition in the media cannot win it in reality either. (Kepplinger, 2001) Well, from this point of view, it becomes crucial that the individual political power centers receive space in the media and the press according to their real social weight, because this has now become a basic condition for the substantive functioning of democracy.

It is no coincidence that in 1986 the German Constitutional Court made a decision in which the requirement of media relations being balanced according to political power relations was raised to constitutional rank. In Germany, this means that parliamentary and non-parliamentary parties must be given press and media space and opportunities to express themselves in proportion to their political weight and proportion achieved in the elections. (I wonder to what extent the left-liberal media predominance and even media dominance in today's Germany of 2021 meets the requirements of German constitutionalism?)

From this point of view, let's also look at how the ownership relations of the media have developed, to what extent has the composition and political orientation of the journalist society changed, has the appearance before the public become balanced between the political trends?

It can be said in advance that the media and press operations of the years of the regime change, and even the first two decades, would not meet the requirements of the decision and requirements of the German Constitutional Court to this day. This is indirectly proven by the fact that, according to a 2000 survey, the majority of the elite controlling the media are left-wing.

Several factors played a role in the development of this situation.

image: Media1

First of all, the process of privatization of the press, which was practically completely state-owned in the previous system, and later - during the Horn government - the appearance of privately owned, mainly commercial media, should be highlighted. It can be concluded that during the regime change, the national and county dailies were predominantly owned by a few Western European press tycoons with left-wing or liberal leanings (for example, the majority of the county papers fell into the hands of the Axel Springer group), nor after the change of ownership, the vast majority of these papers - obviously not independently from the political orientation of the owners - it adopted or pursued a left-wing, socialist or left-liberal orientation. Of course, the choice of the owner and direction was not accidental, as the "media gurus" who remained in place even after the regime change - who decided on the identity of the foreign investor - were of course left-wing. But in most cases, these decisions met the needs of the existing journalistic corps, since the waistline of the journalistic society was socialized during the Kádár era, and the impact of this does not pass without a trace. As a result of everything, after the regime change, there were no significant personnel changes in the field of dailies, the journalists who played a leading role in the state socialist system remained in their place, and even more than once they were included in the ownership management of the privatized newspapers.

On the other hand, after the lifting of the frequency moratorium, in 1995-1996, the possibility to launch commercial media also opened up. A few commercial channels were also created, among which the owners and management of the ratepayers were also left-wing or left-liberal.

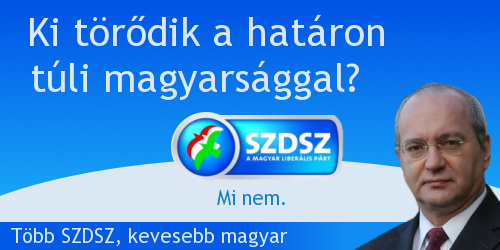

The other factor, which cannot be neglected, is related to the Free Democrats. As I mentioned earlier, the Free Democrats had very good personal relationships in the press and media editorial offices, which they used at first in order to carry out the regime change consistently. However, later, shortly after the Antall government came to power, they turned away from the right-wing government, and from then on, in opposition to the Antall government, a kind of alliance and cooperation was established between liberal and socialist journalists and editorial offices. As a consequence, this legitimized and strengthened the position of the leading editors linked to the old nomenclature, and facilitated the development of the "left-liberal" symbiosis.

image: Fortepan

Finally, the fact that persons with a history of the secret service have not been removed from public positions in Hungary cannot be neglected at all. All of this is important because it is common knowledge that a significant part of the leading journalist guard of the dictatorial regime, quite a few editors-in-chief and editors, undertook or had to undertake secret service tasks. (For foreign correspondents, reporting and cooperation with secret services was practically mandatory and self-evident.) However, during the first period of the regime change, it was often raised - even in 2002, but it died again - that a comprehensive secret service law should be needed, which would cover the also to the leading journalists of the former dictatorial regime, as those who significantly cooperated with the power and served it. However, as we have already discussed, no such comprehensive law was passed, as a result of which even the least sympathetic journalists of the previous system remained in their place, in leading positions. (I would like to note here that in 2005 the parliament once again began to create a comprehensive law on agents, but by the beginning of 2006 this attempt had also fallen to ashes - see a miracle, this time also "thanks to" the decision of the Constitutional Court.) Thus, the media network of the socialist nomenclature was not broken either . did not disintegrate, on the contrary, it grew even stronger with the appearance of foreign owners, left-left-liberal support, and the emergence of new commercial media.

As a result of all this, until the 2010s, until the establishment of the second Orbán government, the socialist power center had a very significant advantage in the world of the media and press, which enabled it to place its political intentions, goals, themes and arguments in the center of public opinion, relegated to the background the right-wing power center with a rather modest media network. And if the already quoted German analyst is right, then this gave the socialist political camp a rather big advantage in the political competition. (The situation changed considerably in the 2000s, the balance of power between the two camps is now balanced.)

Author: Tamás Fricz, political scientist