We have already reported . The Great Delusion – Liberal Dreams and International Realities, published by Yale University Press, has been scrutinized by Krisztina Koenen . His review in German was translated by Gábor Sebes.

A summary of Mearsheimer's views on the principles of - as he uses the word - realist foreign policy, and a theoretically grounded and in-depth analysis of the flaws of liberal interventionism. No matter how much we dislike the realist theory of foreign policy, the book is well worth reading. Because it provides a logical explanation for how the internal liberal democracy of the USA (and Western European countries) is connected with their interventionist foreign policy in the decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Mearsheimer also makes some observations about how the liberal, activist foreign policy has a negative effect on the internal organization of Western liberal democracies. What we are experiencing in Germany today supports them in many ways.

The goal is liberal hegemony

Mearsheimer's thesis is that after the fall of communism, the United States, as the only surviving world power, followed a liberal foreign policy, regardless of the party affiliation of the current president, with the aim of creating a "liberal hegemony" throughout the world. The foreign policy elite, with an instinctive hostility to both nationalism and realism, wants to turn as many countries as possible into liberal democracies.

(It should be noted here that Mearsheimer does not mean the evil, murderous version of nationalism to which the meaning of the word has been reduced in Germany. It is more about the emotional and cultural identification of the individual with the nation of the time and the willingness to stand up for it.)

"Basically, the United States sought to remake the world in its own image," Mearsheimer summarizes. This policy did not fail due to clumsiness or unfortunate coincidences.

It is doomed to failure for principled reasons, says the author, because it contradicts nationalism and realism, whose influence on international politics is legally greater than that of liberalism.

Why is this so? Mearsheimer believes—and the facts support him—that there will never be universal agreement on what the "good life" looks like. Humans are social beings who are shaped by communities from the beginning of their lives. Therefore, apart from the unique personality structure, the individuals' perception of the good life depends above all on the "cultural software" that society has given them during their formative period during daily interactions. Ultimately, reason is the factor that determines what inner convictions a person will follow, but their instincts come from cultural imprinting. This does not mean that man is a prisoner of his emotions and socialization, but "unlimited reason cannot lead to universal agreement about the good life."

Countries, nations and communities are fundamentally different. The geographical location, the climate, the topography, the coincidences of the common history, the peculiarities of the language contribute to the creation of countless customs, traditions and perceptions regarding the "good life".

However, "the greatest differences arise as people exercise their capacity for critical thinking and come to different conclusions about the good life."

Responsibility for the rights of all citizens of the Earth

Yet many people, above all liberals, are convinced that what the good life is based on general principles and objective reality. This idea culminates in the assumption that there are universal human rights that do not even need to be enforced, but are given to everyone simply by virtue of existing as human beings. Mearsheimer rejects the existence of "universal and inalienable" human rights, and not just because their counterpart, world government, does not exist, which he says will never exist. More importantly, "when liberals talk about inalienable rights, they de facto define what the good life is." However, this has dangerous consequences:

"The fact that many people believe in the existence of a universally valid truth, which they supposedly recognize, makes the situation worse, because thinking in absolute categories makes it difficult to compromise and exercise tolerance".

Armed with universal human rights, liberalism is prone to intolerance, even though liberals, as fighters for individual freedom, stand up for everyone's pursuit of happiness according to their own ideas.

Despite this, most liberals believe that liberal democracy is superior to all other political orders, and that this order alone has the right to exist in the entire world.

If we look at the countries of the Earth, it is noticeable that the national conviction is present everywhere, as opposed to liberalism. According to Mearsheimer, liberals exaggerate the importance of individual rights because they have less influence on everyday life than liberals believe.

"In fact, liberalism not only lacks the ability to hold society together, but it has the ability to erode this cohesion and ultimately damage the foundations of society."

While for liberalism, man is the representative of his own interests; he is actually a social being who feels strong loyalty to his own group, family, region, nation and faith community. National commitment is therefore more consistent with human nature and more widespread than interest in liberal democracy.

Liberalism's central assumption that there are human rights leads liberals to feel a responsibility for the rights of all the inhabitants of the Earth and to be ready to intervene anywhere in their interest - even with the means of war.

"Liberal foreign policy is very ambitious and decidedly interventionist." Often, as in the case of the United States, their own nationalism reinforces the feeling that they are above others as liberals, which further strengthens the sense of mission. "There is an explosive mixture of national chauvinism and liberal idealism," writes Mearsheimer.

And so it is possible - in addition to emphasizing the love of peace of liberal democracies - to consider war as an acceptable tool for the protection of human rights and the spread of liberal democracy around the world.

Dividing the world into good and evil

Above all, cosmopolitan elites advance the cause of liberal hegemony. The morally sound slogans of rights and peace, and the well-paying job opportunities in the foreign policy clique explain why the liberal elite is such a devoted supporter of interventionist foreign policy, even if the disaster they cause is foreseeable. And the disaster happens in every case: because people living in nation-states want to define their own politics and reject external intervention. Experience shows that the target country will show fierce resistance, including terrorism.

Liberal foreign policy also makes it difficult to find diplomatic solutions, as liberal states do not consider authoritarian states worthy of diplomatic efforts.

The world is divided into good and evil, between which there is no possibility of compromise, so only unconditional surrender is acceptable.

Only perceived or real great powers can afford a mission-conscious foreign policy. Due to the expected costs, their target area is usually weak countries. After the end of the Cold War, the USA was at the forefront of attacks on the sovereignty of other countries (the Germans also intervened wherever and however they could, let's add). Great powers are capable of military intervention, but the means of intervention are also available to weaker ones: supporting civil organizations financed and organized by them, certain parties and politicians, or even publicly shaming the country.

Hungary and Poland can tell you how this works.

While the interventionist foreign policy has a destabilizing effect on entire regions or even the entire world, it also causes great damage internally, within the liberal state. The fact that governments have carefully guarded secrets in the US did not start with the war in Ukraine.

During the Vietnam War and the wars in the Middle East, individual rights were violated countless times and the rule of law was disregarded.

Mearsheimer cites the Guantanamo prison as an example, the deportation of suspected terrorists to lawless states, but also the eavesdropping of millions of their own citizens. Enemies are suspected everywhere, citizens who are disloyal or even hostile to the war are searched for, critical views are persecuted, the media is targeted, citizens are illegally monitored, whistleblowers are persecuted and silenced.

Yet "it is vital for liberal democracies to minimize secrecy and maximize transparency - but the pursuit of liberal hegemony leads to the exact opposite".

The opposition between realist and liberal foreign policy

Criticism of the liberal sense of mission already draws the contours of a realist foreign policy, as it floats before Mearsheimer's eyes. The odium of cold power politics clings to realpolitik, and its adherents can certainly only lose if compared to the seemingly lofty war aims of the liberal democrats (or our greens). This weakness cannot be changed, since real politicians are neither able nor willing to paint a romantically colored, harmonious picture of the world.

They see the world much more as an anarchic place where there is a ceaseless power struggle. In an age like the present, when there is more than one superpower—as usual—the superpowers aim to maintain the balance of power and improve their own position. Since the non-ideologically driven great powers represent the same interests in their own countries, the anarchic world becomes more predictable and therefore more peaceful, at least as far as the great powers are concerned.

For Mearsheimer, the balance of power is a much more reliable guarantee of peace than international institutions, which he considers ineffective at best, and at worst - and realistic - a tool of a group of great powers or states.

While liberal foreign policy looks optimistically into the future, realists start from the assumption that regime changes attempted to be forced from the outside are without exception doomed to failure due to the ubiquitous nationalism and tribal cohesion. For Mearsheimer, the lack of stability and order are the greatest causes of human suffering, and therefore the steps leading to them must be avoided. Real politicians always count on the fact that wars can have unpredictable consequences and can destabilize countries that are not even part of the conflict. An example of this can be the wave of migration to Europe started by the American wars in the Middle East (to which, of course, the special domestic policies of Western European countries also contributed).

Since real politicians prefer to reckon with the unpredictable, they must be more reluctant to start wars.

Gone is the brief era when America was the sole superpower after the collapse of the Soviet Union. We live in a multipolar world with at least three major powers: America, China and Russia. It is absolutely necessary to refrain from starting wars that aim at regime or regime change or nation-building. Before any war, the crucial question must be asked: "What is best for the American people?"

The full article HERE .

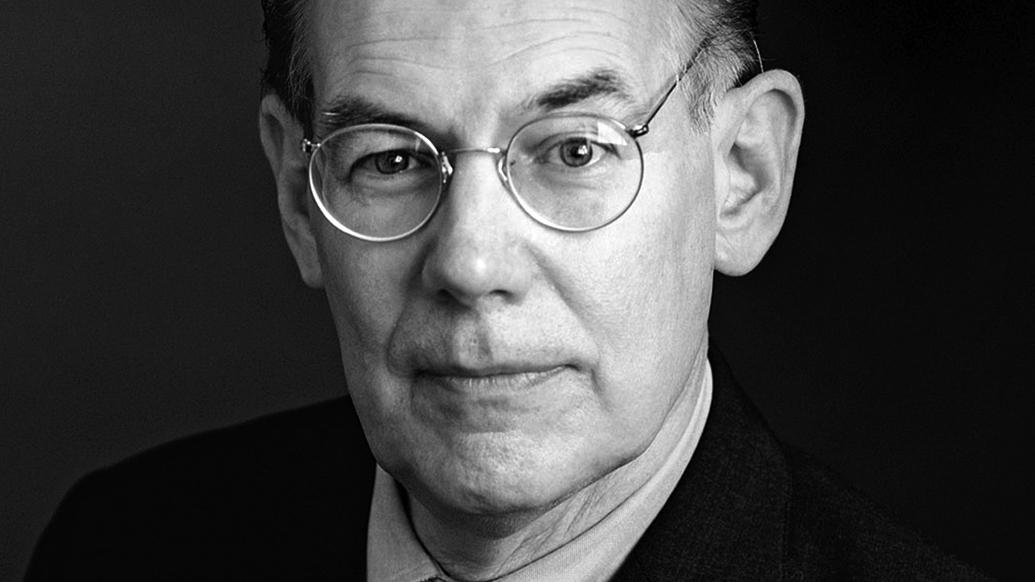

Featured image: John Mearsheimer / University of Chicago News