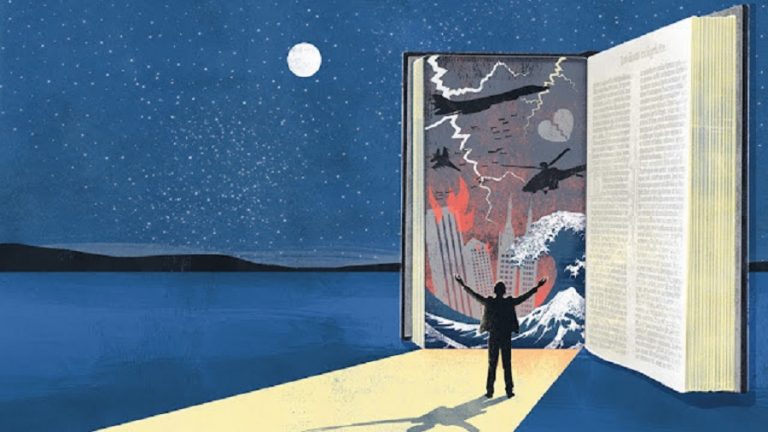

Disaster philosophy in the wake of the two most destructive earthquakes in the history of European thought.

In Lisbon, the capital of the Portuguese empire, on November 1, 1755, on All Saints' Day, the earthquake disaster that shook the whole of Europe at the time and forced the European thinking to stop and respond occurred, in which more than 100 thousand people lost their lives.

Debris and ash covered the city with its beautiful palaces, built from the (robbed) wealth of the colonists. The towers of 30 Catholic churches, which were filled to overflowing, collapsed on the faithful gathered for the festive mass. The horrific, previously unimaginable devastation of the event shook the whole of Europe, not only spiritually, but also European thinking. How could God allow this? millions asked. The analogy is obvious.

How many of the 121,000 people affected by family loss and injuries in the Turkish and Syrian territories, who now claim nearly 30,000 dead, and who knows how many more thousands of corpses lie in the rubble cemetery, and out of the billions of people watching the images of horror, ask a similar question. Where was Allah, where was God?

How is it that decades before the Lisbon earthquake drama, GW Leibniz (1646-1716), who thought through the question of divine justice on a philosophical level, published in 1710 about the goodness of God, human freedom and the origin of evil, rated this world as the best of all existing worlds? Would you have kept your opinion if you lived through the tragedy of Lisbon?

Because Leibniz gave a theoretical answer to the French philosopher, Pierre Bayle, who claimed that the evil experienced and triumphant in the world precludes the existence of an all-powerful and benevolent God. In the theoretical discussion, Leibniz referred to Job and also quoted Pascal, who said that the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is not the God of philosophers and intellectuals.

It is present when and where existential tragedies occur as a result of nature's internal laws and catastrophic potential, as well as dramatic, poignant events of human freedom given to man by God in creation.

Not as a heavenly disaster averter, but as a compassionate Father, the earthly reality of mercy. To notice and take to heart the battered lives lying on the side of the road like a good Samaritan. Even in disasters as God, in the processing of horror as a real disaster as God who shows himself as a spiritual healer. The French Voltaire himself, a contemporary of the time and struggling with the depressing experience of the Lisbon disaster, wrote a philosophical poem a year after the events, in which the question "how could this have happened?" with his thoughts, and writes: Are mortals able to penetrate deep enough into the thoughts of God? In fact, the French skeptic of reason cannot give an affirmative or negative answer.

German, French answer seekers, biblical surpluses

At the same time, the German theological work of FCLesser, who acts with a somewhat fanatical view of creation, which he published in 1738, even before the great drama of Europe in Lisbon, was published with this title: Insecto-Theologia, i.e. Insect-Theology. In this order that can be observed in the lives of insects, our smallest fellow creatures, God contemplates the wisdom, goodness and justice of the almighty. Voltaire also intended Desaster as a response to him. his poem, and later Kant, the pinnacle of Protestant philosophy, formulated his criticism in 1791 in the thought-regulating, cool silence of the clean air on the Baltic coast: all philosophical attempts are doomed to failure in the matter of theodizea, divine justice.

As the only essential question of human existence burdened with the risk of freedom, it posits a meaningful, meaningful, viable alternative to moral action with a chance of survival.

God's divinity cannot be proven or disproved with any kind of disaster theology, disaster philosophy or earthquakes. The question of questions: how do we, humans, behave in such situations, according to common sense and the inner moral command? After all, Kant, Leibniz, Pascal, and even Lesser see the two Old Testament examples as a common denominator. He faced the fiery furnace of human judgment for the joint testimony of Shadrak, Mésak and Abéd-Nego: We have our God, whom we respect, he can deliver us from the burning fiery furnace... but even if he does not, know, O king, what we do not respect your gods (Daniel 3:17-18).

The wisdom of biblical faith - disaster-resolving faith potential

Added to this is the highlighting of the Yobi pattern in Kant, who, after going through an existential earthquake and losing almost everything and everyone, was able to say: I came naked from my mother's womb, naked I will leave. The Lord gave, the Lord took away, blessed be the name of the Lord. Even in this situation, Job did not sin and did not do anything offensive against God (Job 1,21-22). Even in the midst of existential and real earthquakes, devastating and soul-crushing losses, he did not deny God.

Out of gratitude and the memory of his previous grace experienced over many years, he did not become a rebellious atheist. This is not the morality of resignation, but the morality of faith. Not the all-important cynicism of losers, but the greatest treasure even in the midst of losses, the Kohinoor diamond of existence, the unbreakable hope and attitude of gratitude of a person living in the awareness of God's presence.

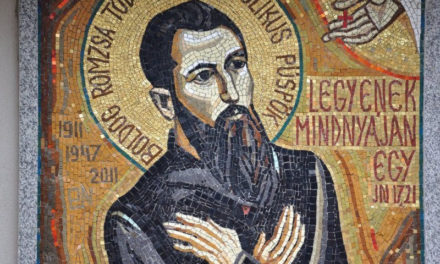

This is the catastrophe interpretation, theological earthquake and destruction theology, the Christian view of faith that our 17th-century religious leaders sang about. Valid to this day: Even if mountains and hills were to tremble/Which were raised by a heavenly hand,/And a departure for the great sky/Would give a sign of destruction:/Even when you see this, do not believe/That this minute will lose you./Zion, until then you cannot fall,/Until God will protect you! (Reformed Hymnal 394.3).

Has humanity reached the final phase of the end times?

The end of the end times? German sociodemographer and theologian Heinzpeter Hempelmann wrote an extremely thought-provoking study recently, even before the Turkish-Syrian disaster, entitled Earthquakes - and what the Bible says about it. He did not publish a catastrophe-theological essay, nor a catastrophe-theological thought-brainstorm. Over thirty pages, he analyzes in detail the natural science and seismological characteristics of earthquakes.

Then how thinkers and philosophers from ancient times to the present have placed this phenomenon among the phenomena of human existence. Then he goes on to say that earthquakes have great religious and existential significance for all of humanity.

Then he turns to biblical findings, and then directs attention to the role of biblical prophecies in world history. Finally, he summarizes the lessons learned in 14 points. It went all the way back to perhaps the most powerful earthquake of mankind, the 1556 Chinese disaster that claimed around 830,000 victims. Some important findings from this exciting and study-worthy essay.

God's presence cannot be excluded from the greatest catastrophe, it is not his preemptive warning that is important. The earthquake is a natural tool that leads to God. It also indicates that a part of humanity, the population of a given area, is in a moral crisis. But there can be a catastrophe with which God erases something from the old, lifestyle, thinking, in order to make room for the new.

It is also a warning, namely that the end of the world will be a truly shocking final earthquake. The omega point of history will not be some rosy or artificial intelligence wonderland, but a cosmic and planetary future earthquake in the full and unsuspected sense of the word. Every generation must prepare for this in spirit, because not even Jesus knows the hour and the day, only the Father.

We don't have time, but we do have the ability to be ready. Earthquakes are "apocalyptic codes" that once upon a time in the Bible, and today in reality, God reminds us that one day everything will end. Permanently and irrevocably. Until then, watchful waiting, preparation before God, positive action, nurturing the hope of survival, and taking seriously the existential alarm and alarm of intervening disasters are all our innovative options.

Earthquakes once and today are not a concrete judgment of God, but a sign of grace that evil has prevailed on a global scale and therefore the entire human well-being and condition has faltered. The biblical apocalyptic, end-time perspective sees a connection between natural disasters and spiritual events, between visible and invisible reality.

According to a prophetic approach, the increasingly frequent and powerful disasters may point to the collapse of the world order.

The visible form of the world passes away - according to the Greek text: the scheme of this world passes away (1 Cor 7:31). The schemes, templates, are for the time, the fashions. Biblical hope does not use, or does not in the least use, the worry, fear, and anxiety caused by the drama of events. He does not consider the events as a means of the mission, rather he is at the service of comfort when they occur. Never forgetting for a single moment that the conviction of common faith is that we await a new heaven and a new earth. Therefore, on behalf of and on behalf of the tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands affected by the disaster, it is our Christian freedom, even our duty, to say: Come, Lord, Jesus! So that nothing is under a curse anymore and the night passes forever (Revelation 22,20; 22,3.5.).

(Dr. Lajos Békefy/ Felvidék.ma )