This is how the reign of Mercy was born, says Father Luc de Bellescize, pointing out that Mercy is stronger than Evil.

"What's your name?" asks the emperor of Rome Ridley Scott Gladiator c. in his movie - "Do you have a name?"

"My name is Gladiator," says the "Spanish", turning around.

"How dare you turn your back on me, slave!" You take off your helmet and tell me your name!”

Then the former military officer faces his enemy:

- My name is Maximus Desimus Meridius, commander and leader of the Northern army, general of the legions of Felix, faithful servant of the true ruler Marcus Aurelius. Father of a slain son, husband of a slain wife, But I'll take revenge in this life or the next!

A true man's triumph

The good must always win in the final duel against the rough and tumble man. At the end of the film, Maximus, the general-turned-slave who challenged the Empire to a duel, kills the man who murdered his wife and son in the arena. The dagger slowly penetrates the throat of Emperor Commodus. He that prevailed by the sword, and was full of anger, violence, and hatred, perished by the sword. An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, blood for blood. The slaves are freed, the gladiator's soul ascends to the Elysian fields to find his wife and child. His hand runs through the fields of wheat ripe for harvest. We can be part of the triumph of a righteous man who was reduced to the fate of slavery. Spectators are relieved to see the emperor's blood drain into the sand.

This is Greek catharsis. In Aristotle's poetry, it is expressed as the purification of the viewer's soul by bringing the suffering of the sinner to the fore. Evil is destroyed, good wins in the end. We are relieved.

It was a nice movie that overcomes violence and we can leave with the satisfaction of having found harmony again. We leave the room with a reconciled heart. The truth has prevailed.

But it's just a movie

This is not always the case in life, because injustice, mediocrity and hatred often prevail. How many times do you have to watch helplessly the humiliation of the good and the success of the violent. However, the feeling that evil cannot have the final say in history is engraved in the human heart. Humans have an instinctive aversion to injustice. Think back to our indignation when class inspectors or helpless teachers meted out collective punishment to us for the misdeeds of someone who was too shabby to ever be caught.

It can be clearly stated that man has an ineradicable desire for justice and peace, as an ineradicable memory of being created in the image and likeness of God, which sin was unable to completely destroy.

It is right for evil to be punished and good to be rewarded. A man should get what he deserves. The role of the state is to ensure the conditions of justice and to watch over its enforcement. This is fundamentally necessary for peace, which, according to Ágoston, is based on the tranquility of order. "Justice and peace exchange kisses," says the psalmist (Psalm 85).

Redemption is stronger than evil

Mercy is not of this world. It is infinitely superior to the justice of men. It consists in dealing with the sinner not on the basis of his sins. I imagine the apostle Peter's shock in the Garden of Olives, when he acts as his master's defender: "Put your sword back in its sheath! He who takes the sword will perish by the sword.” (Matthew 26:52).

Let's imagine for a moment that Maximus spares the emperor, forgiving him in the arena and hugging him to his bosom before inviting him to a cup of drink for refreshment. Wouldn't that cause intense frustration in the viewer?

The film would end on a dissonant note - in human terms, but only in human terms. Because we want to see evil blood flow. Because the blood of the innocent must be avenged.

This is the question from Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov. in the grandiose scene of his novel, which is about the suffering of children. Ivan Karamazov does not want the mother to forgive the gentleman who tore her child apart with dogs. He does not ask for general, free harmony, for the great eschatological feast where everyone is saved, without discrimination. He does not ask for a too easy forgiveness, a debt that God destroys with a wave of the hand, saying that "it is not so serious" and that everything ends with hymns of praise.

"If, according to the will of heaven, it can happen that an innocent child can be torn to death by a wild animal, then I will return my ticket"

says Ivan Karamazov. Malraux lent Dostoyevsky's book to a beggar in Vercors, a member of the Resistance, who replied:

This is a terrible problem because it is the problem of the Evil One. … But Evil is not stronger than Redemption, Redemption is stronger than Evil.

Malraux in the Anti-Memorials. he quotes this conversation with his father in his work. He writes:

"Only the victim can face the torment, and the God of Christ would not be God without the crucifixion".

The turn of history

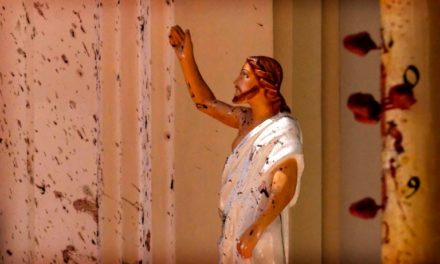

God's humility when he takes our sins upon himself is unfathomable and unfathomable. “Yea, he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; for our peace the punishment overtakes him, his wounds procured us healing." (Is. 53,5). "Is there anyone on earth who has the right to forgive?" asks Ivan Karamazov. His brother Aljosa answers him: "Yes, this Someone exists. He can forgive everything, everyone, because he is the one who shed his innocent blood for everyone and everything."

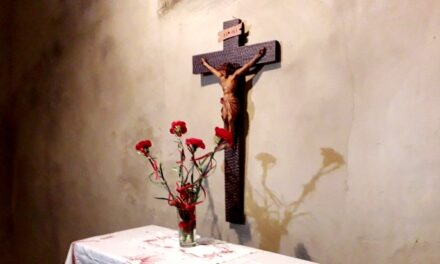

The crucified Christ is the great mystery of the turn of history, ending the hellish period of revenge and the constant repetition of hatred. One day a man did not take revenge. One day a man resigned to send more than 12 legions of angels to destroy sinners. And this man was God. "I am my Lord and my God," says the apostle Thomas, feeling Christ's wounds (Jn 20:28).

Caravaggio depicts Christ as he takes Thomas's hand to plunge it into the wound in his side. The Lord's body is bathed in light, as if he himself were the source of all light. In the background, the apostles are suffering from sins, they are crumbling under the weight of sins, some of them are crying. They seem to emerge from the depths of the night. Thomas is completely shocked by the physical presence of Jesus, he is forced to put his finger into the gaping wound in his side. Tamás' unbelief is often brought up. Tamás does not doubt: he does not believe. This is completely different. He refuses to be told anything. He refuses to win too easily. Common hallucinations are suspicious to him. He won't settle for a cheap apology. He wants to see the wounds, touch them with his hands. Blessed Thomas, who based our faith on experiencing Christ's truly resurrected body, which bore the wounds of suffering!

"Blessed are those who do not see and yet believe." (John 20:29). But through Thomas we also saw Christ. We were also touched by him.

Through him we plunged our hands into his spear-pierced side, as we sink into his heart, with a love stronger than death.

God's Revenge

Such is God's mysterious "revenge", which is quoted by the prophet Isaiah, God who did not destroy his enemy, but paid for it with the price of blood. "Peace be with you," says the Lord. And he showed them his hands and his side. The real peace that the world can never rob us of is the peace earned by wounds. "The apostles were filled with joy."

Real joy is that which has waded through death, injustice and hatred.

Then we can say with St. Ignatius of Loyola in the Anima Christi prayer:

"Hide me in your holy wounds!

Don't let me get away from you!

Protect me from the evil enemy!

At the hour of my death, call me to you!

Grant that I may come to you

and praise you with your saints,

forever and ever.

Amen."

Translated by: Dr. Seidl Ambrusné

Source: Aleteia / katolikus.ma

Featured image: YouTube screenshot