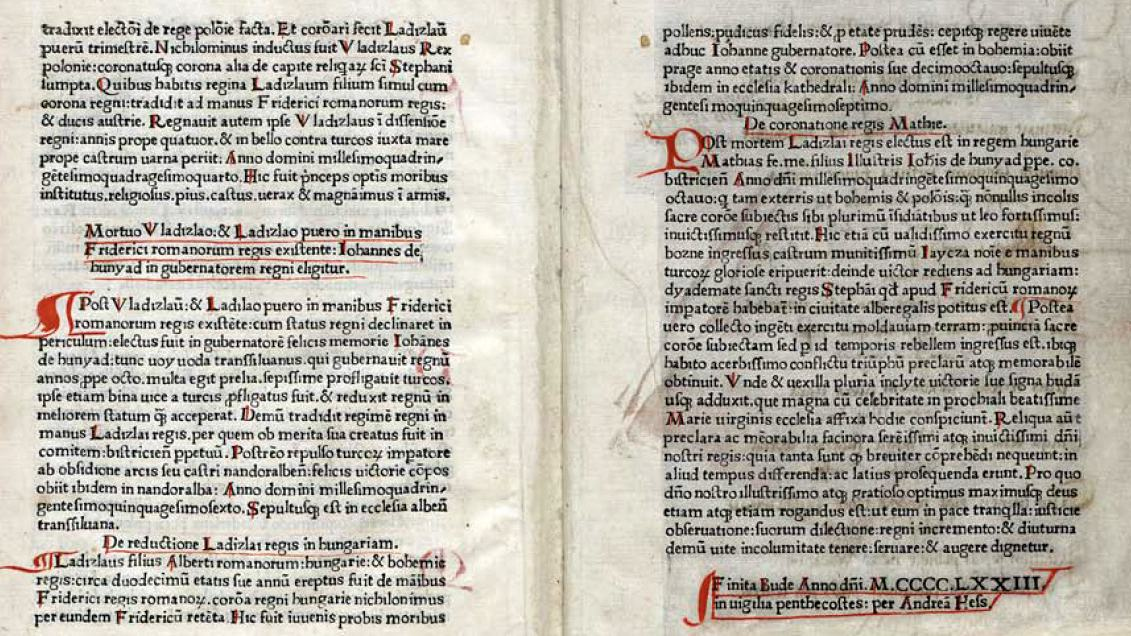

The Budai krónika was published on June 5, 1473, on the eve of Pentecost, from András Hess' printing house in Buda, as its first product - it was the first book printed in Hungary.

Historian Richárd Horváth, senior scientific associate at the Institute of History at the ELKH Humanities Research Center, explains the circumstances of its publication as follows:

“What is certain is that the date is surprisingly early. Remember, Johannes Gutenberg's first printing press began publishing books sometime between 1450 and 1455 in Mainz.”

He adds that in Italy, the cradle of humanism and the Renaissance, this technique appeared only a decade later: in Rome in 1466 and in Florence in 1471.

In many European countries, book printing started later than in our country. The specialist notes that the first known printed volume from Austria, for example, dates from 1482. He emphasizes: at the beginning of the 1470s, the "humanist wave" that had started in the previous decade was still going on in the Buda court. Despite the fact that we are after the suppression of the 1471 rebellion organized by the humanist high priest János Vitéz Zrednai, in these years many humanist scholars still moved around Mátyás, and the ruler's environment was characterized by an intellectual effervescence. It is interesting that when the volume was published, at the time of Pentecost 1473, the king was not in Buda, but in Brno, Moravia.

"Fortunately, we know a person who could have been a supporter of András Hess and the publication: this is Buda provost László Karai. However, we have no source or trace of the number of copies printed," says the researcher. Regarding the title, he notes: we usually talk about the Buda Chronicle, but this is a bit misleading.

The original title of the volume was Chronica Hungarorum, i.e. Chronicle of the Hungarians. The title Budai krónika was given to it by later researchers in the 1740s and 1750s, and since then it has been called that by the public and the narrower profession.

Richárd Horváth points out: the volume's contemporary significance was primarily due to the publication form itself, the novelty of the printed book. “We can be sure that it must have been an experience similar to when the first personal computers went to retail. The possibility that written works could now be duplicated not only by laborious manual copying, but more simply, faster, and in larger numbers appeared. For posterity, the significance of the book is even greater: we are talking about the eponymous volume of the so-called Buda chronicle family, which represents about half of the textual material of the medieval Hungarian chronicle composition. The historians of posterity can be more grateful to Hess for his work than the old residents of Buda," explains the expert.

"Based on our "preconceptions" about the Middle Ages, we would expect the Bible to be the first printed volume, but this only seems obvious from today's perspective. In that era, very few people could read - according to research estimates, no more than 20,000 out of a population of three to three and a half million in Hungary at the end of the Middle Ages - so an edition of this kind could hardly have had a large market," shares Horváth.

An even bigger obstacle is that there was no Hungarian translation of the Bible in 1473, and it was only published seven decades later. A sufficient number of copies of the Holy Scriptures were available in the form of manuscript codices to the narrow, mainly ecclesiastical stratum whose members could read Latin.

"There was, however, a curious humanist audience open to reading, primarily in the royal court, in high priest's seats, in the residences of some aristocrats, who were interested in the history of the kingdom, so this could also be a reason. And let's not forget: the Renaissance itself brought an interest in the past, similar summaries were created all over Europe during these decades," explains the historian.

Ten independent copies of the Buda Chronicle are known to the profession, two of which are in Hungarian public collections, the National Széchényi Library and the ELTE University Library. Another seven volumes are preserved in the great collections of Europe in Vienna, Leipzig, Rome, Prague, Paris, Kraków, St. Petersburg, and another one in the American Princeton. The binding of most of the books is not original, but from the 18th and 19th centuries. century cover. "According to our knowledge, the pieces from Prague and St. Petersburg may be in original binding, and their execution is also very similar, so it can be assumed that they were also made in Buda, in Hess's workshop or at the master bookbinder who worked with him," the historian shares the details.