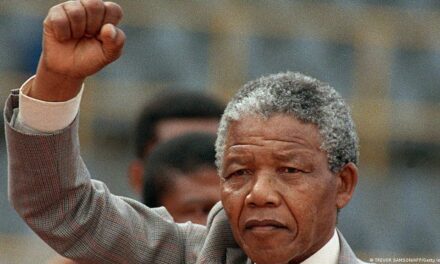

This year, Szent István Társulat, Hungary's oldest book publisher, celebrates its 175th birthday. In connection with the jubilee - approaching Saint Stephen's holiday - we talked with Olivér Farkas, the director of the publishing house, about past, present, trends and tasks.

What historical antecedents helped to found the Szent István Társulat (SZIT)?

The 1825 Bratislava Parliament marked the beginning of the Hungarian reform era, perhaps the most dynamic period of Hungarian cultural history, which lasted for nearly thirty years. Almost in parallel, following the national council of 1822, a process also started in the church, the focus of which was how to renew the Catholic Church in accordance with the new pastoral needs. At the synod convened by Sándor Rudnay, Archbishop of Esztergom, three topics were focused on: the resettlement of the Jesuits, the publication of a new translated Bible, and the publication of new theological books. The council's provisions were absorbed by the bureaucracy, few decisions were implemented, but Baron Ignác Szepessy, bishop of Pécs, and his biblical staff tried to publish a new edition of the Bible, as a revision of György Káldi's translation of the scriptures. Its significance lay in the fact that Káldi's translation of 1626 had been used by the church for two hundred years by then, and had undergone three new editions, in contrast to the Protestants' Károli Bible, the 31st edition of which was published at the time. The Szepessy's translation was not very successful, the explanatory texts in the five-volume Bible were longer than the Holy Scripture itself. After that, Archbishop Béla Bartakovics of Eger commissioned Béla Tárkányi (who as a scientist was a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, later became the vice-president of the Szent István Társulat, as a friend of Petőfi, Kölcsey as a poet - ed.) to re-edit the text of the Bible used by Catholics. In 1865, Bartakovics handed over the right to publish the Bible to the Szent István Társulat. From then on, the volume of the publication of the Catholic Scriptures rose sharply, since before that there was no institution that dealt with this with sufficient intensity.

How is this possible?

At that time, there were no publishing houses in Hungary that dealt with book publishing and distribution in a systematic way. Until then, this task was performed by printers. This lack was recognized by Mihály Fogarasy, canon of Nagyvárad, later bishop, who wrote that in 1842, while singing Christmas carols, he got the inspiration: such a publishing house should be founded. He formulated his idea in 1844 and published it in the newspaper Religio és Nevelés, thus laying down the initial statutes of the Szent István Társulat. After he moved from Nagyvárad to Pest, in 1847 he convened a group of prominent church and secular men and founded the Szent István Society. They were so sure of the favorable judgment of the Viennese court that they designed the Catholic calendar for the following year, which later became one of our most popular publications. However, the permission from the Council of Governors was never received.

All this happened in the spring of 1848. The Szent István Társulat, even as the Good and Cheap Book Publishing Company, was officially born in the revolution, it is the same age. Looking through the history of the Society, it is perhaps not an exaggeration to say that the publishing house became one of the symbols of the Hungarian people's independence, desire for freedom and knowledge.

After the establishment of the new responsible Hungarian government, one of its first actions was to obtain the operating license for the Company. We still keep the entry of Fogarasy, who wrote: they started operating on the first of May. The Hungarian Catholic bishops also assessed that the revolutionary changes had created a new situation, so in the summer of 1848 they sent a questionnaire to the clergy in the country, curiously waiting for their opinion on the changes, including the founding of the Good and Cheap Book Publishing Company. The clergy welcomed the publisher with joy and supported it in everything, with Primate János Hám at the head. At the same time as the social changes, the church was looking for new communication and pastoral opportunities, and book publishing was the most suitable for this purpose. The faithful and the clergy particularly liked the fact that the Society wanted to publish books in Hungarian.

Photo: Tamás Császár / civilek.info

Who would you like to address in the first place?

The greatest thing about the story is that the Society wanted to speak to the whole society. Small pamphlets were published for the lower classes, in which the authors tried to provide support in political, historical, public life and pastoral issues. It is also characteristic that when a president had to be elected, Count István Károlyi, the chief lord of the Pest county, was placed in the chair, and Count János Cziráki became the second president. This is important because the former drew ideas from the French and the latter from German-speaking areas, which publications should be published. Károlyi initiated the publication of a literary magazine, which he also financed. And the launch of Katolikus Néplap, the country's first Catholic weekly newspaper, which was later published as Katolikus Hetilap, is proof of how well the Society responded to new social needs. At the request of the prince-primate, the paper was also published in the Czech language; the Szent István Társulat soon took over the already existing German-language Katolicus Néplapot, so the newspaper was published in three languages. This was a revolutionary change in church communication at the time!

The period leading up to the settlement, the First World War, the Soviet Republic, the Horthy era, communism sometimes elevated and suppressed the Association, there were quite a few challenges in the publishing house's life. What was the decisive idea that kept the fire alive in the founders and their successors all along?

In the history of the Society, the period after the defeat of the 1848/49 revolution and freedom struggle was special: despite the difficulties, we witnessed great spiritual support, since József Eötvös, Ferenc Deák and Ferenc Liszt joined the Society around this time. And the management had the courage to stand up for issues in Vienna, approaching each issue from a cultural, rather than a political, point of view with a smart diplomatic sense. In my opinion, the fact that the Habsburgs were Catholics also mattered, and although they initially did not like the fact that the Society was publishing books in Hungarian, they later turned a blind eye to it due to their shared religious identity. This era was obviously less problematic than that of the Council Republic, when the people's commissars for public education showed up at our headquarters in Szentkirályi utca in the days following the proclamation of the communist form of government and seized the Stephaneum Press. They smashed all the books they found there. The comrades were effective.

They could start all over again.

With the defeat of the Soviet Republic, the Society quickly got back on its feet, because there was a great unity around us. In the twenties and thirties, however, another challenge had to be dealt with: the spread of mass communication. Abbot Ákos Mihályfi of Zirci, the vice-president of the Society at the time, directly believed that the motion picture theater and the radio would destroy us.

Fortunately, this did not happen.

No, in fact, from the twenties onwards, the Society experienced a boom, because in 1922 the management decided to merge the publishing house, the distribution network and the printing house, which had been operating separately until then. This is how the Szent István Társulat Egyesitett Üzemei Rt. was established. A year later, SZIT already celebrated its 75th birthday, during which large celebrations were organized; Cardinal János Csernoch was the keynote speaker at the celebratory assembly, while Minister of Culture Kunó Klebelsberg praised the operation of the Society in front of Miklós Horthy and his wife, as well as the entire episcopal faculty. The management of which, even before the jubilee celebration, requested the cardinal to ask XI. Pope Pius's blessing for the Society, but the prince-primate brought home even more from the Vatican: the Society of St. Stephen received the title of Book Publisher of the Holy See, which gives it the title of the most prestigious book publishers in Europe - such as the Italian Antonetti, the Swiss Herder, the German Pustet, the Spanish Rialp - joined.

In the storms of history, the publishing house has made a lasting impact in many important areas, one of the most important of which is textbook publishing. Why did the Szent István Society start dealing with this area?

As early as 1850, the leadership lobbied for the publication of textbooks, more intensively, of course, after the settlement, at the Ministry of Culture in Vienna. The reason for this is that the schools were largely maintained by the churches. We simply needed our own textbooks. At that time and in this way, for example, the first Hungarian literature textbook was born.

How many different languages have textbooks been published in?

In twelve languages, the languages of all the peoples and nationalities of the Habsburg Empire.

This was then - indeed, even today! - was quite extraordinary.

We continued this activity even after the collapse of the empire. During the Second World War, in 1940, after the decisions in Vienna, we also delivered new textbooks to the schools of the regained territories. The Company also opened two new stores, one in Galántá and the other in Kassa. At that time, our books were published in the largest volume: the number of copies approached three million in 1942!

Such antecedents were followed by one of the darkest periods in the history of the Szent István Society during the four decades of communism. How was the publisher able to survive this period and what losses did it suffer?

The Society's warehouses were full of theology and textbooks, which the communists decided were out of date, even though Margit Slachta spoke out in parliament against the destruction of books, and the bishops protested in vain. Enormous calamities befell us in 1948, instead of celebrating the centenary, we shared the fate of our main patron, Cardinal József Mindszenty, who was imprisoned in December of that year. Our headquarters in Szentkirályi Street, built by count Nándor Zichy, was nationalized, although the comrades "graciously" allowed the CEO of the Society and the president of the Szent István Academy, which had been established in the meantime, to live in the building. This was also the reason that all costs had to be borne by the Society, even though the building and the printing house were no longer owned by it. By 1951, the publishing house was completely bled to death, with not a penny left in its account. Although the communists drove CEO Ernő Takács to commit suicide, the Society did not cease: Archbishop Gyula Czapik mediated between the Rákosi and his creation; he also appointed the lay papal chamberlain Miklós Esthy as "delegated administrator", whose written legacy sheds light on many things about the era.

This could certainly have been the subject of the bargain: SZIT can remain if it is led by a person loyal to the new state power.

That's more than likely. During these years, the Association published very few publications, which had to be presented to the State Church Office in advance. Not to mention the fact that since the establishment of the Ecclesia Cooperative, which is connected to the peace priest movement, the book distribution rights of the Szent István Society have also been taken away, handing it over to Ecclesia.

Do you think it is conceivable that the Communists did not abolish the Association because then - since SZIT was called the Book Publisher of the Holy See - they would have been in trouble with the Vatican?

It is possible that this also played a role in their decision! According to a legend, Archbishop Czapik spoke to Rákosi and asked him: "Comrade Rákosi, is there freedom of religion in Hungary?" "Of course it is," replied Rákosi. "Then who will publish the Catholic textbooks?" asked the archbishop. "You have that publishing house, publish it!", the communist leader closed the debate. Can we believe the legend, did the discussion have any consequences? It is true that some books were published in the years after '56. This strictness lasted until the 1970s, when we were first allowed to receive paper from abroad as a gift, until then the state provided our publisher with a certain amount of paper each year. From that time, the number of copies began to increase, and from the eighties we were able to distribute our books again, and we were even able to open a small shop in Kossuth Lajos Street, District V.

Who wrote works at that time?

In the 1950s and 1960s, the more well-known secular authors were advised against the Association, and of course self-censorship was already in place. Fortunately, however, even then there were people with straight spines who defied authority, such as teacher Zoltán Kodály, who gave his last work, the Hungarian Mass, to the Society and waived his fee. This is how Sándor Sík's Te Deum was published, which was also set to music by Kodály. We are very proud of that.

What path has the Szent István Society followed since the system change?

From 1948 to 1989, there was also a one-party system in Catholic book publishing. Although the State Office of Church Affairs checked the content of the manuscripts, the current state bodies determined the scope, number of copies, and even the selling price of the books to be published, yet people stood in line to buy almost all of our publications. This is how we achieved the system change, when about seven thousand book publishers were registered in Hungary over the course of a few years. A great chaos arose because, despite the book dumping, the secular distribution networks were collapsing, and it was difficult to start again. The monopoly of the Szent István Társulat in its territory also ceased, and several Catholic publishing houses began to operate. However, thanks to our own distribution network that had already been established, we survived this period as well, because people knew us and knew that SZIT was authentic. Still, we felt the competition due to pirated editions.

Didn't they try to legalize these bad cases?

Of course, in several cases, but in the end we realized that it is better to leave this to the market: we significantly increased the number of copies, reduced the sales prices, so the "pirates" bled to death in the price war in a few years.

What happened to the Company's former properties?

XXXII of 1991. the law required the settlement of the ownership situation of former church properties. With reference to this, we tried to get our building on Szentkirályi Street back, the lawyers cost us a lot of money. However, at the last hearing, we were informed: the legislation says that only the church can get property back, and the Society cannot. We agreed that the Catholic Church would get the building back, trusting that we would get it for use. However, the law faculty of Pázmány Péter Catholic University also announced its claim to the building complex, so the church, after receiving the building, gave one part of it to the university and the other half to the Szent István Társulat. Then, as fate would have it, the university began to expand and asked for our areas as well: they got it, with the exception of a part the size of a bookstore and storage space.

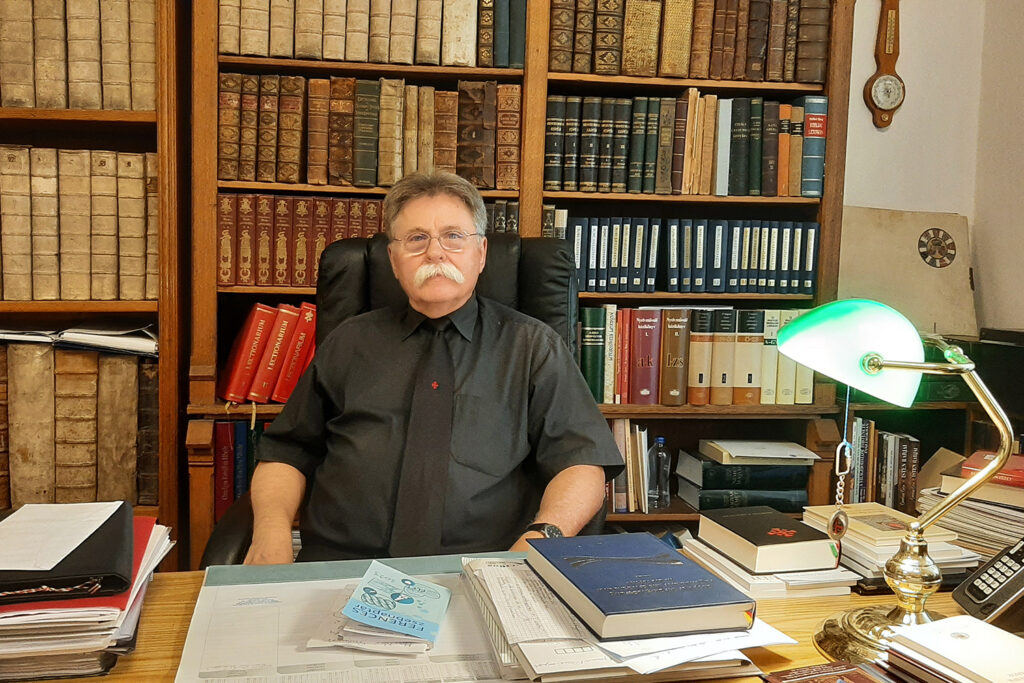

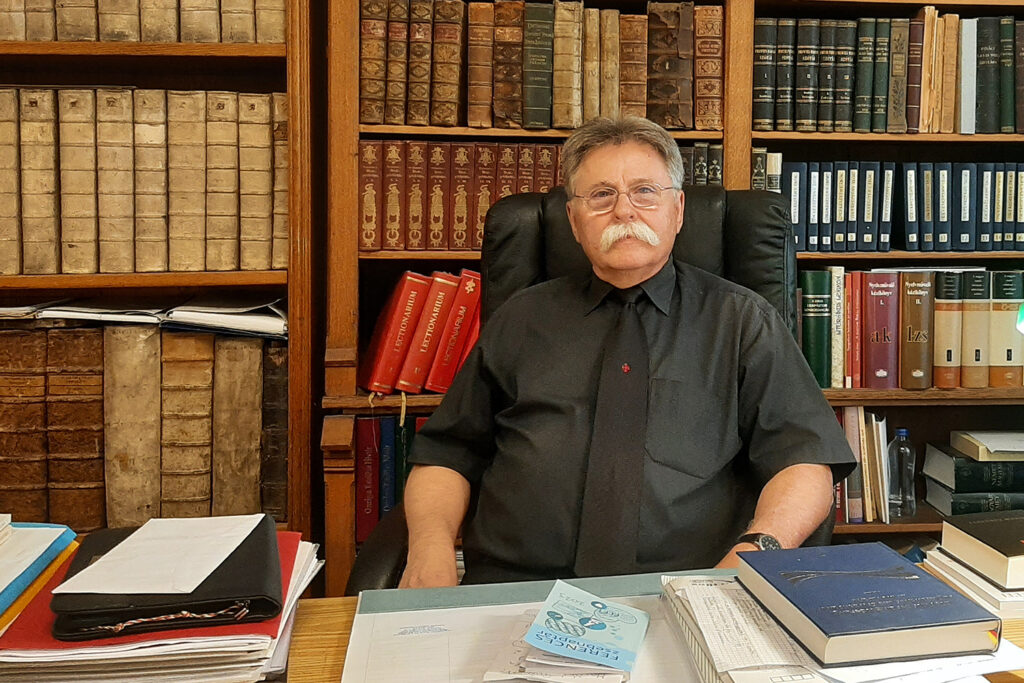

Olivér Farkas, Szent István Society, Photo: Tamás Császár / civilek.info

What was the main focus after the system change?

As in the heroic times, this time too we saw an opportunity in textbook publishing, preferably in higher education. We also managed to obtain full publishing and distribution rights for the publications of the Pázmány Faculty of Religious Studies and Law - the latter in exchange for the ceded property parts. In addition, since 1992, we have organized and coordinated the Szent István Book Week every year, modeled after the Holiday Book Week, which has been our most successful form of book distribution ever since. The quarterly Szent István Book Club newspaper, which we recently published in twenty-five thousand copies, became a version of this extended to the level of the Carpathian Basin.

This is a huge number in today's conditions.

Indeed, and looking back at the old total copies, the difference is not big anyway, the difference lies in the number of published books. While previously we achieved 3-400 thousand copies a year by publishing fifteen works, today this requires one hundred, one hundred and twenty publications. However, this is not a unique phenomenon, it is a general trend. In order to stay afloat, we have to work much harder. After the change in the system, we tried to highlight those authors who had a different image in education during the decades of socialism. This was the case, for example, with Attila József, who was known as a proletarian poet, but we published his godly poems, and so did Árpád Tóth, Mihály Babits and Bálint Balassi. We brought out the French and German classics and we have a world literature series. Literature can also be put at the service of faith.

This is perhaps related to the fact that in 1992 the Szent István Society and the Stephanus Foundation established a special prize to reward authors with a Christian spirit.

Indeed, the Stephanus Prize, in the theological and literary categories, is awarded annually to authors who represent the values of universal Christian culture in their works published in Hungarian. To date, a total of 62 people have received this award, such as Cardinal Ratzinger, the later XVI. Pope Benedict, Zsuzsanna Erdélyi, Éva Fésős, István Nemeskürty, Katalin Dávid, Sándor Kányádi, or Cardinals Péter Erdő and Robert Sarah. I don't think any of them need an introduction.

How did the Society respond to the challenges of the digital age?

A few years ago, we decided to make our old and new books available in digitized form. We try to make the Society's publications and our archive as widely known as possible, if only because we had to move several times during our history, which resulted in serious data loss. Half of our library and documents are currently gathering dust in Szentkirályi Street, because for the time being we cannot place them elsewhere. We digitized a significant part of our documents in connection with the 175th anniversary, and we asked the cardinal and Archbishop Ternyák for permission to carry out research in the Esztergom and Eger Archbishop's Archives. In the process, many valuable documents from the Society's past were found, which are published on the Arcanum database's sazkatars.hu page, together with about four thousand society publications, as well as the previously mentioned Miklós Esthy legacy.

Can they fight, and if so, with what means, against the effects of secularization and consumer culture? Is it their job at all?

What we can do is to monitor Catholic book publishing in the world, primarily the activities of the Vatican Publishing House. Two of our series are based on this: the Papal pronouncements and the Roman documents. More recently, we have also drawn a lot from overseas examples, because American book publishers are ahead in this fight, since the phenomenon started with them earlier. In their publications, they give answers to these processes in a light style, yet serious, not infrequently neo-Thomist arguments. We have already published several, mainly apologetic, publications from them.

What are your plans for the next century?

I would not go that far in time: we are already working on the new liturgical books according to the guidelines of the bishop's faculty and its liturgical institute - it is a huge work that will last several years. Its first fruit, the new missal, has already been published. Thanks to the bishop's faculty and pedagogic institute, it became complete this year, so the 9th-12th grades will be in the schools by September. our grade humanities public education textbook series. Furthermore, we are taking care of two major works: János Kodolányi and György Rónay - we want to continue both series. And all this, as in the past, in the future: in the service of Hungarian culture and the Hungarian Catholic Church.

Author: Tamás Császár

Cover image and photos: Tamás Császár