That's how it goes with identity.

Nagyvezekeny is located in the late Bars County, in the valley of the Zsitva River, north of today's Hungarian-Slovak language border. According to Hungarian local history literature, the name of the village refers to the Vezekeny family, and it is already mentioned in writing from the beginning of the 13th century. It is not far from today's Hungarian border, Esztergom and Komárom are both about 80 kilometers away from Vezekeny, i.e. good riding ground. However, do not look for this name on the map!

Veľké Vozokany is the honest Slovak name of the village, and according to the 2001 census data, one, that is, only one brave Hungarian still lived in the then pure Slovak settlement of 556 people. None today. This is not only why the village does not have a Hungarian name, but also because historical Hungarian place names cannot be used officially in Slovakia. Sometimes exceptions are made only when, for example, the Venice Commission comes to the country for an inspection visit. However, it would also be good for Slovak national self-awareness that the name of such a small Slovak village appears in a source written (in Latin) eight hundred years ago.

The general use of the Latin language in Hungary simplifies the Slovak inferiority problem, there is no need to prove anything that the Hungarians deliberately misspelled Štěpán to István. Stephanus Rex can be their king in Latin. Actually, it could be true, since the Hungarian kings were always the kings of the Carpathian basin and the peoples living here.

Nagyvezekény's former Hungarian life is not confirmed by anything other than its name and its owners. During the century and a half of Turkish subjugation, the region was continuously considered a conflict zone, its population was destroyed, Slovaks living in worse living conditions moved down from the mountains to the empty houses and villages. Elek Fényes called Vezekény a lake village two hundred years ago, and since regular censuses have been taking place, it has been datable as well.

We could forget Nagyvezekény if there was not a monument with a lion on the border of the village, similar to the lions guarding the Parliament. It is not by chance that the artist's personality connects the two works, the bronze lion of Nagyvezékény was also made by Béla Markup. This is the lion

"proclaims peace and security in a protective stance while smashing the Turkish battle flag with his paw".

The triumph is a thing of the past, the Turkish symbols were stolen, even the bronze statue was liked by metal collectors, and in 2013 they tried to dismember it and steal it. Later, motivated by those who wanted to erase the past, the Hungarian inscription was sprayed with paint.

In short, the monument stands there, proclaiming the glory of the 1652 victory over the Turks. Who knows how many Turkish raids this was in the first hundred years, when the central half of the country was divided into vilayets and sandjaks and conquered by the Turks. Nagyvezekeny, located in the conflict zone, belonged to the Sandzák of Esztergom, and the villages of the Sandzák with a dwindling population were regularly looted by the Turks. Not only the crops and farm animals, but also the people living there fell victim to this. The villages were set on fire, the animals were driven away, the serfs were captured and dragged into serfdom. The soldiers of the end castles tried to act as forcefully as possible against the Turks, they also did this on August 26, 1652 in the Nagyvezekeny border with the army of Mustafa Bey of Esztergom, who was called a robber.

The Turks numbered about four thousand, and the army of the chief captain of Banyaváros, Ádám Forgách, assembled from the surrounding outlying castles, may have been a third of that number. "I set out with 600 Hungarian and German horsemen, 150 musketeers and the same number of hajdús," wrote the captain in his report. The Hungarian lords of the area, the Esterházys, the Pálffys, and the serfs who could wield weapons joined him with their soldiers. The Hungarian cavalry routed the Turkish army, and some of the prisoners were freed. About 800 Turks remained on the battlefield, the loss of the Hungarians was only a fraction of that. Still, it was considered powerful, because four lords, four Esterházys remained on the battlefield, Ferenc, Tamás, Gáspár and the son of the illustrious Miklós Esterházy, nominated as palatine successor, László. They formed the two flanks with a few dozen soldiers, and although they heroically withstood the pressure on them, in the end they had no chance against the overwhelmingly superior Turks. The desecrated bodies were buried with great pomp in the crypt of the Jesuit church in Nagyszombat. Balassagyalmati captain Ferenc Esterházy, for example, without his head, because the Turk took the head of the fallen lord and took it with him as a trophy.

That's how Hungarian was spoken at that time.

According to the current Slovak understanding of history, Hungarians and Slovaks fought heroically and side by side in this battle. This cooperation would be necessary even today, which is why a joint statement on Hungarian-Slovak unity and reconciliation was issued. In the spirit of the declaration, a Hungarian from Hungary and from the Highlands came to Nagyvezekeny on this year's anniversary of the battle to place a commemorative wreath at the foot of the lion.

Fortunately, the commemorators who believe in reconciliation are late for the wreath-laying ceremony of those who do not believe in reconciliation.

The latter covered the pedestal of the statue with a giant Slovak flag, and planted two more Slovak national flags in the ground to the right and left, as if appropriating the Hungarian triumph for themselves. There was no room left for the Hungarian flag, not even for the wreath. In any case, it would have been removed from there right away - was the local explanation based on experience - just as it does not make much sense to place an information board in Hungarian at the monument. On the one hand, because the local mayor would not agree, and on the other hand, because the Slovak nationalists would immediately blow it down, tear it down or remove it from there. (I quietly note that the Hungarian sign may not even be displayed if the memorial site is considered an official memorial site.)

We talk little about the fate of Hungarians in the highlands. And yet this area is where the Hungarian statehood, the Kingdom of Hungary, continued to live.

The institutions fled here from the territories occupied by the Turks, the Parliament from Pest to Bratislava, the Palatine from Buda to the same place, the head of the Catholic Church, the Archbishop of Esztergom, to Nagyszombat. They took refuge in the Highlands with church treasures, nobles with their valuables and themselves, they fought and shed their blood waiting for better times. Uncountable values of Hungarian culture went to the Highlands, and most of them remained there. In the 20th century, the Slovaks did not need the Highlands, but the Czechs, and they hoped for a larger Czech country from the acquisition of the Hungarian territories. The plan met the ideas of the great powers, they received 61 thousand square kilometers from the Kingdom of Hungary and more than one million Hungarian people. 900 thousand from the Highlands, 180 thousand from Subcarpathia. Because in Trianon, Transcarpathia was also awarded to the Czechs. This is how (great) Czechoslovakia was created.

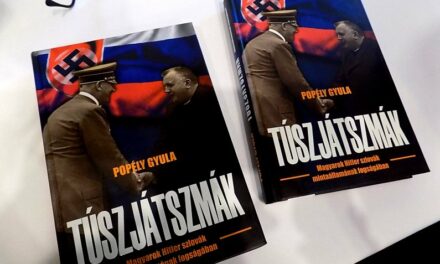

President Masaryk's best student, Eduárd Beneš, then did everything to get rid of the Hungarians.

We can thank him for the anti-Hungarian kisantant, the vertical constituencies that changed the predominance of Hungarians. We can thank him for the anti-Hungarian and anti-German pogroms after the Second World War, displacement, exile, demotion, second-class citizenship, and collective guilt. The Czech communists tried to continue the Beneš traditions. The fear of assuming the Hungarian identity that continues to this day, the Hungarian name emerging behind the Slavic writing style, the opportunism of "we are Slovaks" can be traced back to Beneš. The world of "Bélas".

Half a million Hungarians disappeared from the Highlands in a hundred years, and today they make up only eight percent of the Slovak population.

Hungarians disappeared from the big cities, Bratislava and Kassa grew into socialist and Slovak nationalist cities. Can this still change? The need to stay in one's homeland is a need that is looked down upon in a globalist world. Everyone wants to be happy, no matter where and how. A Hungarian from Slovakia told me recently:

if Hungary becomes rich, suddenly a lot of Slovaks will become Hungarian again. That's how it goes with identity.

I believe in community building. A community survives if it sticks together, and of course if it has representation. It would be nice if Hungarians in Slovakia believed in the power of unity!

Featured image: MH/Róbert Hegedüs