The world today has two capitals, Washington and Beijing; and Viktor Orbán is the first Hungarian prime minister whose name is known in both. Written by Mátyás Kohán.

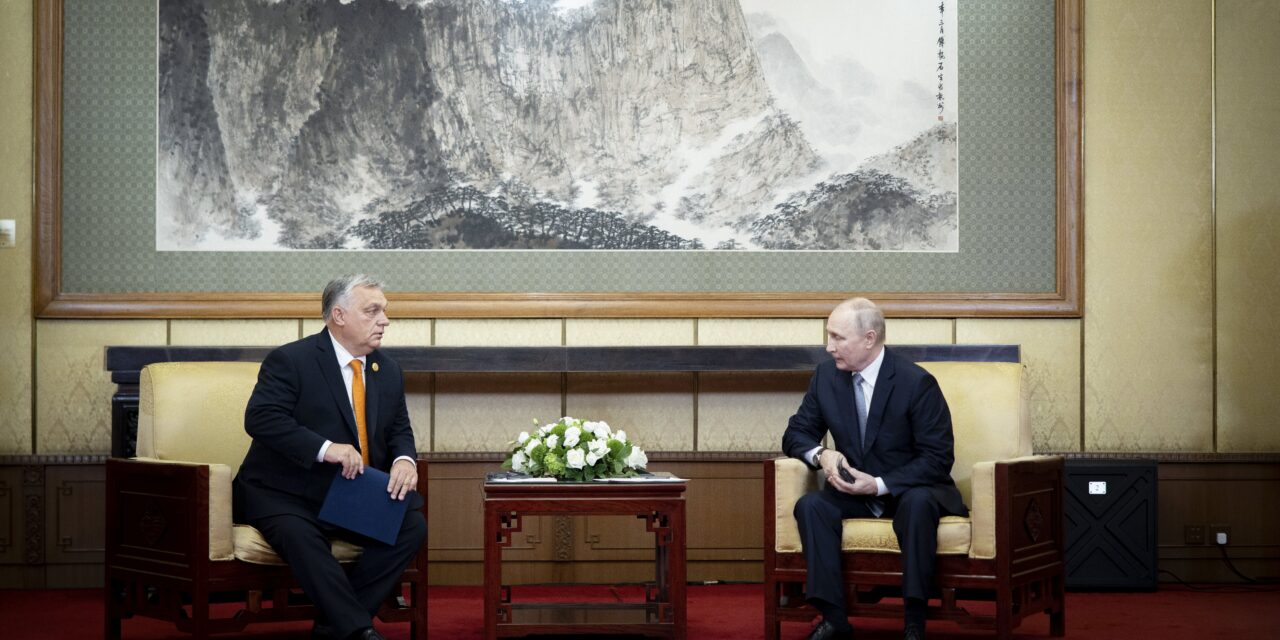

"Hungary's strategy clearly shows how the world should be." The words of star economist Jeffrey Sachs from June are ringing in my ears as I watch with bated breath as the Hungarian Prime Minister does the two things in quick succession that are anathema in the cultured West today: he goes to Beijing and shakes hands with Vladimir Putin there. From the point of view of should, these are the most natural things in the world.

However, the should is in the conditional mode, and we live the world in the statement mode. And this is where the problems begin.

Because from an American point of view, Viktor Orbán went to the capital of the world's dictatorships. (Remember: although the world missed this as much as the glass Palestine missed the Abraham Accords, since 2021 the United States has lived under the spell of the struggle between democracies and dictatorships.) On the other hand, it shakes hands with those with whom one should not shake hands. (Remember: from the Bucsa massacre in March 2022, for some reason it was concluded that the best way to avoid massacres is to stop the peace talks and let the massacre continue.)

If you look at the globe as a whole, Hungary does not have any isolation problems. On the contrary: a few years ago, we broke down the firewall of indifference around us, which separated Hungarian capital from the West and non-Western capital from Hungary, or Hungarian products and technologies from the Eastern market.

For now, we are only loosening our global isolation to the extent that, say, the Czech Republic, Germany or Italy have managed to do so for a good two decades.

The world today has two capitals, Washington and Beijing; and Viktor Orbán is the first Hungarian prime minister whose name is known in both. The former president of the United States, who is likely to be re-elected, only speaks of him in superlative terms, while the Chinese president calls him his friend. He's a big hitter.

This is not the way to isolate yourself.

The negotiation with Vladimir Putin is a completely different genre in comparison: after the critics of the Hungarian government's pro-peace stance are keen day and night that Viktor Orbán always only calls on the Western partners for a ceasefire and the end of arms deliveries, now he has also called on the Russian president to be peace. You can tell that this happened from miles away: in diplomacy, it is not customary to say things like "our positions are far from always the same" (a direct quote from Putin) in front of rolling cameras, and that "the answer I received from the Russian president was not the least bit reassuring". (direct quote from Orbán).

This mutual, open discourtesy clearly indicates that there was definitely a clash here in connection with the war.

Something like this used to happen to Péter Szijjártó, too, not infrequently. (Incidentally, the official was recently asked whether Orbán is pro-Russian. In Putin's answer, he indicated that "this is stupid, he has no pro-Russian feelings". It is worth listening to him, he does not usually deny his friends.)

Even the dog in the West doesn't want to hear this. There are many people who do not understand. There are far fewer who get it, but it just doesn't fit their narrative. Unfortunately, the latter have the microphone.

Hungary does not have a problem of isolation, but a problem of understanding.

Our allies don't understand how we operate—and we understand our allies' political systems about as much as a chicken understands a multiplication table. We do not speak their language properly, neither concretely nor figuratively, and they are not very interested in ours. It is due to this and nothing else that they do not understand: the pro-peace position is, in the noblest sense, a pro-Ukraine and pro-European position. Ukraine would gain blood and territory, Europe would gain competitiveness if it represented this; we'll bear with you to argue about the details, but that's clearly the intention. Being angry with you is noble, not treason.

But it is also due to the lack of understanding that we are not able to understand even God: Western electoral systems are not conducive to a political force that thinks like us being able to form a stable government.

Just as we are not able to understand that the European parties that sympathize with Fidesz do not necessarily have the political knowledge of Fidesz - this is how it happened that the closest ally of the Hungarian government in Poland was able to fail to win the most important campaign issue of the Polish voters, the issue of the economy (in the same way, just as the Hungarian opposition could not find its place in the war issue last year), and then, a few weeks before the election, with a major change of direction on the Ukraine issue, it is good to salami its only coalition partner that can be taken into account.

You cannot build a policy on the fact that the local Fidesz will take over power in the countries of the West one fine day. Foreign policy must be designed for the existing world, not the way the world should be.

It is unacceptable that our relationship with a country alternates between mutual respect and arch-enemy depending on election cycles, and that we fall out of the window in the absence of a sufficient amount of mutual respect. This is our half of the understanding problem.

In short and concisely: in the Budapest-Brussels conflict, we have to swallow a frog like the Ukrainians in the Ukrainian-Russian war.

There is no suitable military solution to this conflict for us. No matter what brainless things the European mainstream thinks about the world, we will not win against them. That is why we need an immediate ceasefire and peace talks instead of further escalation. Not because the opponent - in the case of the Ukrainians, the Russians; in our case, Brussels - he would be right about anything. But because it is unwinnable, it is unnecessary to wage a self-absorbing war even for the best cause.

The West will behave tolerably towards us only if we are tolerable to them; a balance of mutual tolerance must be found. Giorgia Meloni, Robert Fico, and even the Maltese party-state succeeded, and Hungary, which is much smarter than these, will also succeed.

We must learn to be tolerable allies or we will get nowhere.

A good solution also requires good problem recognition. There is no question of isolation; if Viktor Orbán's trip to Beijing conveys anything, it is that there are more open doors for Hungary today than ever before.

But in order to enter them, we must honestly understand the world, the driving forces of its actors and our own room for maneuver. Through understanding and knowledge, we will be successful in our natural associations and in the world outside them, simultaneously.

A little Czech, Romanian and Italian never hurt anyone.