Saturated churches and endless processions - Gyula Hámori's former photos contradict our opinion of Hungarian churches from the last century. They clearly show: despite all prohibitions and repression, the faithful persisted even in communism.

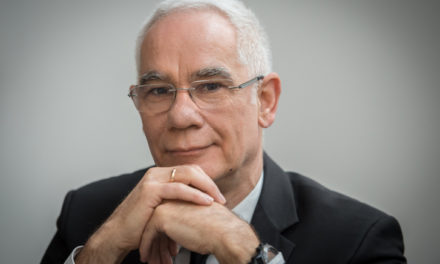

How can this be? Church historian Viktor Attila Soós talks about this in the interview.

There are currently 2,450 photos of Gyula Hámori on the Fortepan website, and we can safely say that any museum or historian would be happy if the negatives had landed with him. The photographer, who lived between 1913 and 1977, worked in Budapest, his workshop was at Lázár utca 13, then at Király utca. After the Second World War, he was also employed as a wedding photographer: from 1946 to 1950, he captured three hundred lagzis, leaving for posterity very exciting shots of young people smiling in the courtyards of ruined synagogues, who have been through who knows what, couples getting married at the age of seventy, restrained or fancy ceremonies. Although we do not deal with this topic in our article, let us show you some pictures - it would be a sin not to publish them when we talk about Hámori.

The photographer's industrial license was revoked in the fifties, so he became a company photographer at the United Bulb. From 1955, he worked in the Catholic press, for the newspapers Kereszt and Katolikus Szó, capturing the biggest religious holidays, processions and priest ordinations of the 1950s and 1960s. The photos - most of which have never been published - strongly contradict the stereotypes we have about the practice of religion under socialism. We don't see empty churches, especially not terrified people looking at us from the pictures. What is the truth, what was the life of believers like before the regime change in Hungary? We sought the answer to this question from Dr. With church historian Viktor Attila Soós, member of the National Remembrance Committee.

"First of all, it is important to point out that throughout the socialist era, persecution of the church took place in Hungary. The proletarian dictatorship tried to liquidate the churches with varying intensity and selected methods, because it saw in them an opponent. However, regardless of the measures taken,

the faithful practiced their religion, terror here or there, they went to church"

- interrupts the specialist.

In 1946, many religious communities were abolished, restrictive provisions were made against the church press, and efforts were made to push religious people out of society. In 1948, the church schools were nationalized, and in 1950, the operating license of the monastic orders was revoked. "At first, the Communist Party's idea was to abolish the churches, as they did in the Soviet Union, for example. When it was realized that this was not possible here, surveillance came to the fore, and they wanted to control and use the churches," says Viktor Attila Soós.

In 1951, the State Church Office was established, which supervised and controlled the operation of churches and the activities of priests and pastors. An important part of the exercise of control was that only members loyal to the party were allowed to take leading roles in the churches, thus the peace priests movement was created, which created tension within the denominations between the cooperating and oppositional priests. The latter were prominent enemies of the system, and the government made an example of them more than once, because they believed that if they beat the shepherd, the flock would disperse.

"The hardest persecution of the church took place in the fifties. Concept trials and proceedings against the church mostly affected the upper clergy, but the faithful were also observed. They tracked who goes to church" -

explains Attila Viktor Soós.

Going to church was therefore a disadvantage - but a disadvantage that most people accepted despite the consequences.

If someone went to church ceremonies or enrolled their child in religious education, they could be told about it at work, or maybe because of this they were denied promotions. Other times, he failed university studies if the admissions officer's faith came to light.

In those years, of course, if someone worked as a teacher, was employed in a senior position, or was a party member, church attendance was not allowed, and it was also questionable whether a party member could attend a church wedding or funeral. On occasions related to religious events, the man of the state was usually there, who wrote formal and informal reports on, for example, how many people were in the church, what they were talking about, and what the public mood was like.

At the same time, the government also tried to secularize occasions and holidays connected to the church at the national level, so Santa Claus replaced Saint Nicholas and thus Christmas became a pine festival. Important events belonging to personal life would also have been separated from the church, the celebration giving the place of baptism its name, and church weddings and funerals were replaced by state ceremonies. Since the complete ban could not succeed, they tried to make the new alternative desirable, for example

couples who tied the knot only in front of a registrar and not in church could receive extra financial support.

The removal from religion was also helped by the fact that far fewer people could get by in the countryside than before, so hundreds of thousands of young people were forced to start a new life in the cities. There, separated from their (and) habits, they could easily find new types of programs and entertainment opportunities in the communities supported by the state, many of them replaced the occupations related to religious practice with these.

After the tragic series of events in the fall of 1956, retaliation did not escape the churches either, although 1956 is not a boundary from the point of view of church history, the same processes took place before and after it. After the movements, the party mainly focused on young people, it wanted to keep them away from belief in God.

"In 1958, the foundations of the system of religious persecution were summarized in two decisions. They separated the ideological struggle against religion and the ecclesiastical reaction, that is, the struggle against hostile churchmen. The former was supervised by social organizations, the latter by the political police"

- shares the church historian.

The largest – and also the last large-scale – series of anti-church lawsuits, the Black Ravens case, ended in 1961. One hundred and seventeen house searches were conducted in twenty-seven settlements, as a result of which eighty-six defendants were sentenced to a total of three hundred and thirty-eight years in prison. Roughly half of those involved were civil servants, and half were church workers.

In the mid-1960s, the socialist regime was already fully working to win over the leaders of the churches and get them to support the party-state, and to keep the faithful away from their religious communities through blackmail and manipulation. Although the surveillance of churches was common until the regime change, drastic steps did not take place until the 1970s.

So what do we see in the Hámori pictures? Well, the church historian has already partially answered the question: people persisted in their faith despite oppression, fear and reprisals. If they only went to church once or twice a year, there is a good chance that they were there at Easter or Christmas - when Gyula Hámori was also present with his camera. The pictures therefore do not show the gray everyday life, but rather that there was a critical mass in Hungary, whose members did not give up their faith despite the numerous attempts of the party leadership.

Featured image: Fortepan / Gyula Hámori