It's strange that nowadays it has become fashionable to "protect" children from funerals and mourning, because, so to speak, they haven't grown up enough for it yet, they don't understand, it just wears them down.

I don't remember the first funeral in my life. Maybe it was my grandfather's in 1992. He was over seventy, I was nine. Our relationship was not particularly close. Then there was always a funeral every few years. Most of the time, distant acquaintances of the family died, or relatives that our parents counted on, but we don't anymore. And as I grew up, of course, the farewells of close relatives and friends increased.

On January 1, 2010, towards the end of a meeting in Taizé, Poland, I received a text message from my mother: my grandmother had died.

We had visited him a few days before, but he had not been around for a long time. Recently, my mother and her sister, i.e. her two daughters, visited her in the home where they were taking care of her (she wanted to move in, as the residents were given a suite and all her girlfriends lived there). I haven't seen it in a while. On the way home, there was an oppressive silence in the car.

It was shocking for us, the grandchildren, to see the crumpled body, as it sometimes mutters unconsciously, its hands sometimes move back and forth.

It didn't come as a shock to my mother, as she was a regular visitor to the whole process. I didn't even think that was the last time I saw him alive. When I received the text message, I thanked the heavens that I was with the family for the last visit (and firmly asked the home and my mother to give her the anointing of the sick).

Then we found ourselves in the village cemetery, bone-deep in the cold at the ceremony.

I learned of the death of my grandfather's sister, who lived with us for twenty years or so, in the hospital. He was already over eighty, but he looked old even when we were little. It represented permanence for us. I went to visit on a quiet Tuesday afternoon - it was my turn. I arrived too late to meet him - but the doctor told me: he was dead. I was shocked, I suddenly wanted to call the relative who took care of him the most, I pressed the number, someone picked up, I told the phone that he died, then it turned out to be a wrong call - I apologized, hung up the phone, dialed again, now it's the right one number.

Our relationship was not without friction, but it was still loving. I felt his presence for years after that.

At five o'clock in the morning, I woke up to receive a text message. It was sent by my former classmate, who apologized for not being able to pay his long-standing debt of ten thousand forints - I barely remembered it. When I woke up and opened Facebook, I was faced with the fact that he had died - more precisely, he had committed suicide. Second attempt, this time successful. He jumped off his grandmother's balcony. He had a lot of debt. And we liked it. And then I realized: a few hours earlier, at five in the morning, I actually received a goodbye text message.

The last high school reunion in Kecskemét started with meeting in the cemetery - three of our classmates are buried here.

There is someone who was taken by cancer and left behind three children in addition to his wife, who was left alone. Some were hit by a truck, became mentally disturbed, then became homeless, and finally died. Several of the university acquaintances have already left, even though they have barely experienced half of what is usual today.

And there is Bandi, my old good friend, who is buried in the cemetery of his own town. It was very depressing to read on his coffin at the age of 35: "he lived 36 years". It's very strange that when I think of calling him, I can't call him.

Or there is my father and grandmother - my father's mother - who said goodbye for good just a month or two apart. My father had been ill for a few years. When my grandmother was told, she said she didn't want to bury any of her children. He solved it. A little earlier, but he left. My father still presided over his funeral, although he could barely speak. We knew what was in store for our father, but it was like he would still be with us for a while. So I went to Transylvania. And then suddenly my mother called me - when I saw her looking, I already knew why. I went to the village cemetery, called my godmother (who was next to my mother). Then I went home. My grandmother was 85. My father is 58.

And as time goes by, you get more and more news of death. Aunts and uncles who we barely remember die. Then close acquaintances, friends, relatives and family members also die.

As a child, I stumbled a lot in cemeteries, I especially liked the old, abandoned cemeteries, it was exciting to dig out what was written on the headstones. As an adult, I wandered in the national cemetery on Kerepesi út, or in an abandoned cemetery in Rákosszentmihály.

The cemetery is a place of rest. A bit melancholic. Kinda weird. it's a bit creepy. It is hard to imagine what it must have been like to go from here to there, what the last moments must have been like, what it must have been like to be dead. Of course, according to atheists: if any at all.

They took us to the funerals. Not all of them, but they took me. There was no mention of "kid, he won't get it yet" or "let's spare him". We had to be told that if we would never see someone again, and why. Of course, as a believer, it might be easier. But not much.

It's strange that nowadays it has become fashionable to "protect" children from funerals and mourning, because, so to speak, they haven't grown up enough for it yet, they don't understand, it just wears them down.

I think this fashion is one of the contemporary psychological fashions, all of which aim to save us as much as possible from unpleasant things, conflicts, challenges, and difficulties. What remains is, in the words of Pink Floyd, a "pleasant relaxation".

In order to protect our mental health, we don't want to face disturbing things. Indeed, our mental health would be protected if we faced reality, because then we would be able to develop resilience.

If they talk to the child after the funeral they took him to, he won't break down because of the loss. He will process it. And when, years later, a close family member, relative, or friend suddenly leaves, for example, you have to go to grandma and grandpa's funeral, you won't be faced with the thing we call grief, not then and there. Of course, you can "spare" the child and not let him near funerals or cemeteries until he turns 18, only after that he will bear it much better when the ground knocks on the top of the coffin than if he had experienced it before and could have expected it.

This knocking, the sound of the earth falling on the coffin, is the most shocking. The low point. But you have to live through it.

Of course, all of this is part of a wider problem in this world: it is unpleasant to go to the cemetery - especially if we live far from the resting place of our loved ones. But really, we just want to save ourselves. We have nothing to do with death. But the cemetery is continuity with the past. With our own past. You can go out and talk to the dead. It is also recommended by psychologists. To talk to ourselves. With God. To face.

Below us are the dead, above us is God - we are surrounded by our own, we are not alone.

Folk tradition followed mourning well. And he didn't run away from the dead. According to the ethnographic lexicon, All Saints Day (November 1) and Day of the Dead (November 2) were days rich in customs:

"On this day, it is still customary to clean and decorate graves and light candles in memory of the dead. According to folklore, the dead visit their homes at this time, so it is customary in many places to set the table for them as well, putting bread, salt, and water on the table. Hungarians from Bukovina bake, cook and take the food to the cemetery and distribute it. They light as many candles at home as there are dead people in the family. In the villages along the Ipoly, those who cannot go to the cemetery light candles at home on All Saints' Day. In the past, they watched whose candle was lit first, because according to the belief, it was the person who died first in the family. In the area of Szeged, they baked an empty cake called all saints' cake or kodus cake, which they gave to beggars waiting at the cemetery gate so that they too could remember the family's dead. Even during the feast, the cakes baked on this day were distributed among beggars standing and praying at the gate of the cemetery, so that the dead would not visit their homes. In Jászdózsa, while they were burning a candle in the cemetery, they left the lamp burning at home, 208so that the dead could look with their eyes on it. They believed: 'While the bell is ringing, the dead are at home.' In the villages along the Tápió they put a bowl of food on the table for the dead."

"On the night between All Saints' Day and the Day of the Dead, according to popular belief, the dead say mass in the church. On the Day of the Dead, they entertain the poor and beggars. In the Gyimes Valley, they used to say: 'We cook for the Day of the Dead, bake loaves and give them to the snowmen.'

There are places where they put food on the graves, for example in Topolya, but they also give it to beggars. On the Day of the Dead in Ipolyhídvég, close relatives ate lunch together, then went to the cemetery and lit candles in honor of the deceased. There was a ban on washing on the day of the dead, and even during the week, for fear that the dead person returning home would end up in water. It was also forbidden to wash during Csallóköz, because the clothes would turn yellow. They didn't whitewash because the worms would infest the house. No earthwork was done in Slavonia on the Day of the Dead either, because anyone who violates this would be punished. In Csantavér, many adults were predicted to die from the rain on the Day of the Dead in the following year. Today, All Saints' Day and the Day of the Dead are a celebration of remembering the dead in both cities and villages: going to the cemetery, cleaning the graves, and lighting candles are mandatory for almost everyone. The celebration of the Day of the Dead with lighting spread in some places only as a new custom, after the Second World War, for example in the villages of Kalotaszeg."

This year, the volume The Meaning of Mourning was published in the United Kingdom, in which fifteen philosophers, including Balázs Mezei, wrote one chapter each on death, loss, and grief. The philosopher of religion puts it this way:

"There is an anti-mourning tendency in today's culture, which is related to digital culture, it wants to set aside passing away, to ensure human immortality, to save human identity. Body parts that no longer fulfill their function can be replaced, people wear glasses, dentures, there are organ transplants, why couldn't something be implanted in the brain? This transhumanism actually makes people manipulable. In my opinion, however, Trauerarbeit (mourning work) cannot be spared, classical death processing cannot and must not be forgotten. Consider, for example, that soldiers report that those who have been killed face-to-face will not forget their faces for the rest of their lives."

It is better to face death and the cemetery at an early age, so that we can properly face our fate, rather than run away from it. So that life can be peaceful and we can say goodbye with dignity - and one day we can leave ourselves.

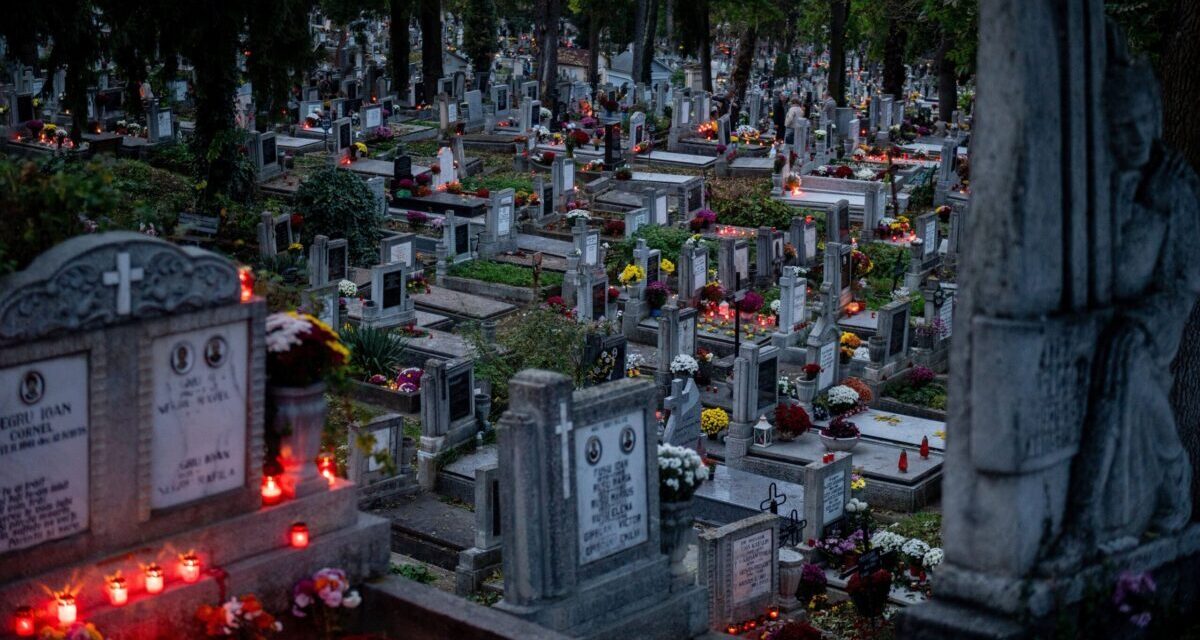

On the day of the dead, in better weather, the cemeteries of the well-kept villages are all softly lit by candlelight.

In some places in Transylvania, the day of the dead is called: lighting.

Cover image: Graves in the Házsongárdi cemetery in Cluj

Source: MTI/Gábor Kiss