Klaudia Brassai wanted to save her father's farm, the work of a lifetime, which she did for 27 years, but when she and her husband jointly took it over and thought about it further, something was created from their boldness that is admired in Székelyföld.

150 cattle, cows, heifers and calves live together in a spacious barn. None of them know the chain, and when they feel like it - and their udders are sufficiently tense - they line up to be milked by their robot owner. In the meantime, they receive a tasty "reward snack" from the device, robot food, which is a ready-made supplementary feed, so they wouldn't even think of missing the highlight of the day.

It could be a few lines of a utopian fairy tale, but it is more real and closer than we think: in Miklósvár, Kovászna county, the smart stable was formed based on the ideas of a young couple, which saved a family farm focused on manual labor and made it operational in two years with the push of a button.

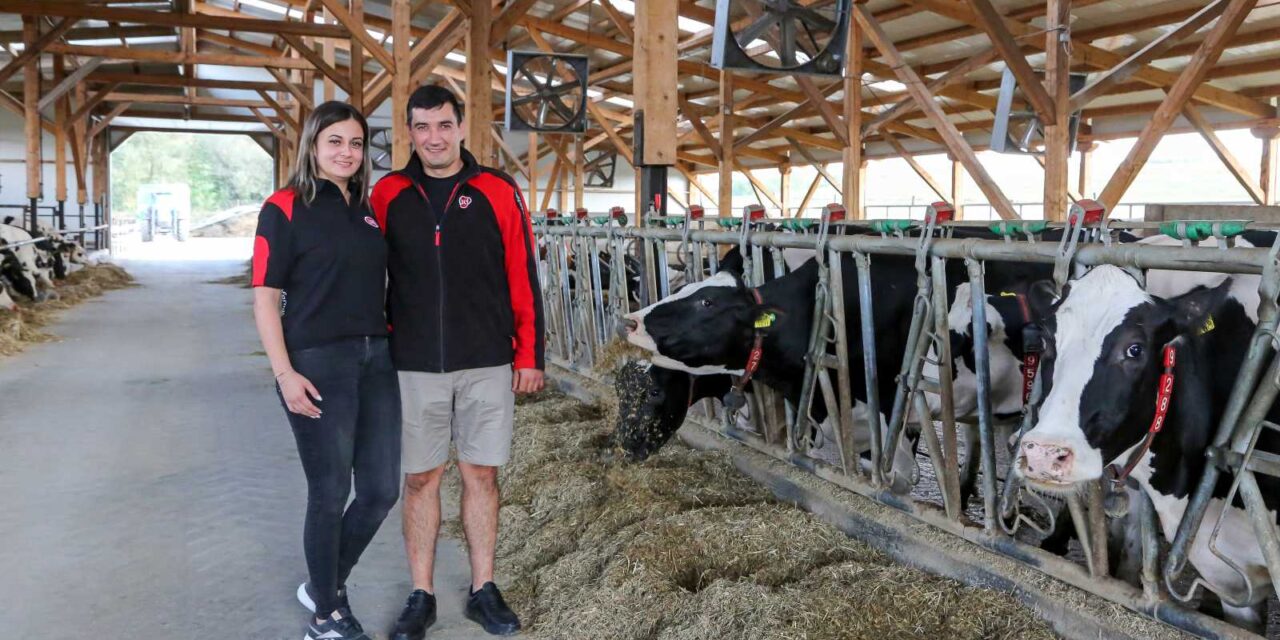

Klaudia Brassai wanted to save her father's farm, "the work of a lifetime, which he did for 27 years". But when she and her husband took it over and thought about it further, their daring created something that is almost unique in Székelyföld, and there are only 92 of them in operation in the country. A robotic farm that increased the amount of milk delivered per day by 33 liters per person.

The story of Klaudia Brassai and her husband Attila Brassai went viral on social media. The Romanian press was the first to write about their robotic farm, which is where we learned about their unusual activity.

The landlady gladly agreed to tell us the story as well, explaining over the phone that their main intention as a young couple was to lighten the burdens of the previous generation. However, none of them had farmed before, even though both families kept animals, they were not forced to work. Her husband even tried his luck abroad, but he soon came to the realization that they should settle down and stay at home, because they have a job at home.

"After 27 years of farming, my father admitted that he was tired of the constant physical work and the constant search for workers. He was prepared to liquidate the economy, no matter how painful it was for him. It was a lifetime's work, I couldn't let it go"

- recalls Klaudia Brassai about the life situation two years ago, who until that point did not take part in work around animals. For him, studying was important, and his parents encouraged him to concentrate on that instead of farming.

After high school, he completed his university studies in Brasov and Bucharest - studying to be a food engineer and inspector - and never thought that the family farm might need him someday. The desire suddenly awoke in her, and her husband supported her in her decision, who delved into the operation of robotic farms, participated in forums, trainings, courses, visited farmers who operate robotic farms, agents who sell this technology, and thus became familiar with the innovative solutions.

The greatest help was provided by Lely's employees, who willingly contributed to the arrangement of the barn so that it perfectly met the needs of the animals and the operation of the robotic technology.

Because in addition to wanting to help, they also sought independence from work - it was important to them that the preservation and expansion of the farm did not mean that a lot of work would suddenly fall on them - this is how the idea of the smart farm was outlined, which is really less it involves physical work, however, it requires full and all-day presence. The robot sends notifications, numerically indicating how much a cow has eaten, how much it has drunk, whether it has chewed enough, and what health indicators it has. For example, it has a high body temperature, is sexually mature or ready to mate. The owner must respond to this, even if most of his activities are limited to working in front of a computer.

150 of 70 cattle; 2,200 out of 500 liters - where did the young people start?

He also reports that they had a regrettable experience with the labor shortage, which justified, among other things, the shift towards new technologies. Although it may seem like an easier way, it was much more difficult, as it required a complete change: they had to move out of the village and build the stable from scratch in the right place. One million euros were spent on it, including the equipment and the purchase of the machines. The investment was realized with own funds and bank loans.

"When we took it over, there were 70 animals, my father kept them in the barn of the family porta in the village, in confined conditions. Our first task was to build a new barn. Which corresponds to animal welfare aspects. We built a 120-seat room, switched to free-range housing, and acquired the milking robot"

- Klaudia shares with us, emphasizing that when the cows were kept in the pasture or in the old barn, the amount of milk delivered did not exceed 500 liters, which sometimes dropped to 300 liters after the onset of drought. However, with the transition to robotic milking, the average daily production also increased significantly, rising to 2,200 liters. And in addition to milk production, the quality has also improved.

As he says, the animals had to get used to the strange "master", but they adapted to the milking robot in two or three weeks. The feed mixture, which was put together by a nutritionist, helped them in this. This is a treat made from our own meadow hay, alfalfa hay, barley hay, Sudanese grass, beer sorghum, sunflower, soybean meal, corn silage and cracked corn, which is fed to the animals in a different way for each group. Because they know that there is a treat waiting for them in the milking room, they don't really miss the daily milking. We also learn from Klaudia that they are currently working on installing another robot, because their goal is to grow from 150 to 250 cattle.

The countryside, where the farmers are each other's support: they are characterized by kaláka and joint burden-bearing

Klaudia Brassai also enthusiastically tells us that farmers are not alone in their work in Miklósvár and its surroundings. They joined an association, bought machines from tender sources, and not only use them together, but also work together during larger works, i.e. they go out to the field with the existing tractors and help their partner who needs them. It is like a cooperative, a kaláka, where, in addition to own property, the progress of others is also important.

The entire article can be read on the Maszol.ro portal!

Featured image: Revista Ferma