"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated.

The assessment of Louis the Great

Louis I of Anjou is an outstanding figure in Hungarian history, whose era-defining actions elevated him to the ranks of our great rulers.

According to the general consensus of historians and researchers and readers who want to know and understand the 14th century, Lajos Anjou was an excellent politician, general, lawmaker, a lover of and understanding the arts, and a brave person in terms of personality. However, there are those who want to gain professional recognition and fame for themselves - and this does not only apply to Louis I and his time - by painting a negative image of the person in question, or of an outstanding era of Hungarian history, in the name of historical loyalty. (It should be noted that many of them do this in the name of science in order to tarnish the history of Hungary, which is full of internal and external attacks and tragic events that cause a lot of damage, even in the decades considered positive .)

One of these serious, if not the most serious, charges against King Louis is the execution of Charles of Anjou of Durazzo and the circumstances surrounding it.

During the first Neapolitan campaign already mentioned in the previous section, Louis summoned his Italian opponents who had given up further fighting to Aversa, in fact for a peace negotiation. Louis of Taranto, Johanna's new husband, did not take part in this, he fled to Avignon after Johanna, under the protective wings of the Pope. However, Róbert and Fülöp of Tarantó, as well as Károly of Durazzó and his brothers Lajos and Róbert went to the meeting. King Louis invited them to a feast and treated the five princes with respect and treatment befitting their rank. However, during the cheerful dice game that followed the feast, Lajos suddenly changed his voice. He accused them of the murder of his younger brother, Prince Endre, in 1345 and of supporting Johanna. The list of Károly's crimes did not end there. The conflict between the two Anjou families - the Neapolitan and the Hungarian - began with the death of the Neapolitan King Robert the Wise in 1343. Róbert left in his will - thus breaking the agreement made with the Hungarian Róbert Károly - that the throne of Naples could only be inherited by his daughter Johanna, and after her death by his younger daughter Mária, by no means by the Hungarian prince Endre. The history of Johanna and Endre's marriage is well known. However, it is less well known that the then 14-year-old Mária was kidnapped and married by Károly Durazzói. With this step, he definitively ruled out the possibility of inheriting the Hungarian Anjou branch. (The fact that he previously supported Louis's campaign in Naples did not change his crime either, because he hoped that with the fall of Johanna and Mary's rise to power, he would be able to ascend to the throne.)

Károly could not avoid his fate. King Louis had already planned to ensnare the princes. Károly Durazzói was executed in Aversa at the place where Endré was murdered three years earlier. The other princes were taken to Hungary as prisoners and later released. However, neither the Pope nor the rulers of Italy accepted the Aversa murder as legal, which damaged Louis' popularity there. To this day, this act provided the reason for the negative assessment that Lajos was a volatile, unpredictable ruler who made many wrong decisions.

Louis of Anjou earned the epithet Great already at the end of the 14th century, when we can read the Latin word Grandis in front of his name in the chronicle of the Venetian embassy secretary Lorenzo de Monachis.

However, the adjective was only confirmed in the Hungarian public consciousness by the poems, prose, and essays of 19th-century romantic literature and history. After all, Dániel Berzsenyi, then János Arany, Sándor Petőfi, as well as the painters, sculptors and writers of the time raised King Louis to the high level of historical memory. This was not only due to his campaigns, which consumed a lot of money, his incomparably multifaceted foreign policy, his activities to expand the country, and his economic measures. His legislative work, his lasting works of ecclesiastical and secular architecture and sculpture, and his creative activity resulting in a cultural effervescence dwarf those negative traits that "investigative historians" so gladly bring to the surface.

The laws of 1351

The country-building decisions of Saint István and King Saint László, II. In addition to the Aranybulla constitution of European importance published by András, the laws of Lajos Nagy published in 1351 defined the Hungarian Middle Ages. Moreover, they had a decisive influence on the Hungarian legal system for five centuries until 1848.

The first and most important part of the legislation is the Ancestry Law issued in Buda on December 11, 1351.

Due to its title, it confirmed the legislation of the Árpáds, especially the Golden Bull, but amended its 4th article. This article originally stipulated that the nobleman had the right to sell his possessions and other possessions or transfer them to anyone. Louis put it into law 129 years later, so that the noble could not freely dispose of his chattels, it belonged only to his descendants by blood, including side relatives. In the absence of descendants, or if the entire clan gave its consent, the property became the property of the Holy Crown. It is not difficult to see that this system of inheritance arose from the ancient tribal-national legal system, before the adoption of Christianity, i.e. it can be traced back to the time of national ownership. This is nice from a Hungarian king born of an Italian father and a Polish mother, who supported the undivided form of family estates. The wise ruler knew well that this would increase the country's military power and the nobility's commitment to the king. (However, it should be known that this resulted in many, many lawsuits and often unfair decisions. But it is no different today.)

However, it must be realized that this law strongly hindered development in the 18th and then the first half of the 19th century. It is no coincidence that one of the most controversial elements of the work of count István Széchenyi /Hitel-1830/ and then of Ferenc Deák, as well as of the reform-era parliaments, was the law of primogeniture.

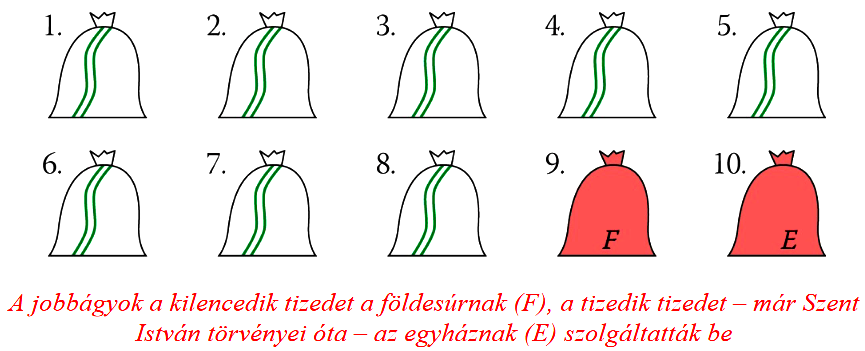

Among the economic measures, the Ninth Law stands out, which reformed taxation. This, like the other laws, served the interests of the commoners. Contrary to the custom of the previous centuries, the new rule prescribed the taking of the ninth, i.e. the ninth tenth. The payment of the tenth tithe, the tithe, has been prescribed by law since Saint Stephen, which included the tax due to the church. Of course, the landowner also had to pay a tax, which, however, was not regulated. The tax to be paid to nobles was originally prescribed by customary law. Over time, it followed that the large landowner was able to collect the tax due to his power, but the commoner and the small landowner could no longer. The latter were often left without serfs, because they settled on the land of the large landowner who provided them with an easier livelihood. Louis ordered uniform tax collection, which meant that all nobles had to collect taxes. Those who were unable to do so, or who did not want to collect the tithe in order to attract the serfs, the king collected the tax instead. The serf thus had no interest in moving to the landowner's land, because he did not receive tax exemption there either.

The institution of the court of lords played a significant role in Louis' legislation.

This judicial ruling, like most laws, arose from the system of Hungarian customary law. Over the centuries, the social coexistence of the Hungarian people was initially unwritten, and then many of them regulated the lives of the king, nobles, merchants, artisans and peasants in written form. The court of lords, i.e. the nobleman could judge his serf, was in practice before. The law of 1351 confirmed this and, unlike before, extended it to more serious crimes. This increased the power of the nobility and strengthened their loyalty to the king.

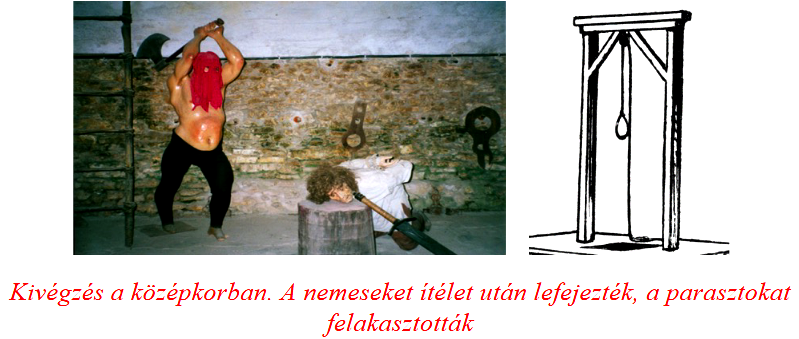

Legislation of 1351 includes pallos law.

Commoners could also judge minor crimes. Criminals caught within the boundaries of the estate Except for the death penalty. It could only be exercised by the king and the barons. Only nobles could be executed with pallos, non-nobles were executed on the gallows. (The gallows set up at the border of the estate indicated the nobility's pallos rights. It should be noted that the first such provisions appeared already during the time of Róbert Károly.)

Among the legislations of Louis the Great is the system of re-donation practiced from 1343. The point is that the property can be inherited not only by the descendants indicated on the donation letter, but by all persons who are members of the family (ethnicity). This law meant that, either without a lawsuit or with a lawsuit, a significant part of the estates could be redistributed.

Hungarian settlements in the 14th century

There were approximately 14-15,000 villages and presumably 500-550 village-like market towns in 14th-century Hungary.

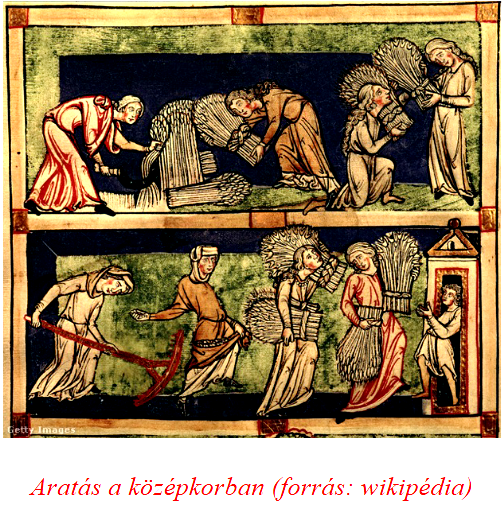

According to calculations, an average of 25 families lived in each village, and each family had 5-6 members. In addition to the villages with approximately 150 inhabitants, the population of market towns and cities did not show outstanding population numbers either. The number of "united nobility" formed by the 14th century can be estimated at around 45-50,000 people. The leading stratum was made up of 35-40 families, and among them came the paladins, the bans, the voivodes, and the high-ranking royal officials. They, the barons, were at the head of the familial system. This familial system - in terms of its structure, services, and interdependence - was closer to "family" relations than the Western European feudal system. But the uniform serf system was established in the time of King Louis, which could have been formed as a result of the services. The basis for paying the tax, the robot, the ninth, the tenth, and the gift was the serf lot. However, the peasants were also landowners, and were taxed based on the size of their small or large holdings.

Citizens of today live in misconceptions about both taxation and the amount of work. They mistakenly know that the medieval peasant living in the villages lived in unbearable conditions compared to today's people and at a level close to starvation. It is surprising that in the 14th century the number of working days did not even reach two hundred. How could this be? In addition to the 52 Sundays - when there was a strict work ban - the Easter, Pentecost, and Christmas holidays, which covered many more days, and the celebration of nearly forty saints, already amounted to more than a hundred days. This was accompanied by important family days - births, weddings, funerals - which often lasted for a week. And the tax rate was smaller than during the crippling exploitation of people by later "advanced" capitalism. Of course, this serf lifestyle changed from country to country, from estate to estate, from period to period.

Due to their legal status, population, and economic power, the cities could be free royal cities, council cities, personal cities, mining cities, and Saxon cities. The free royal cities were already in the 11-12th century. were formed in the century. The first such settlement was Fehérvár, which after Esztergom also played the role of the royal seat. Seven settlements could boast the title of royal city, which were strengthened during Sigismund's reign. As their name suggests, these cities depended solely on the favor of the king. The nobleman, on whose property the settlement was located, did not exercise any rights over it.

Among other things, market towns differed from royal towns in that they could not be surrounded by walls.

This meant that the city did not enjoy as much protection as the royal city, and it also did not have the right to hold fairs and stop selling goods. They had to pay taxes, but in contrast to the villages of Jobbágy, they could pay taxes once a year. The cities of Tárnok were a group of royal cities. They had privileges, among other things, they had an independent judiciary, and instead of Fehérvár law, they used Buda law, which was practiced by the tárnokmeister. Another group of free royal cities was made up of personal cities. Its citizens could appeal to the royal personal representative in legal cases. The personal representative was the court representative of the king's person. These cities include the settlements of Esztergom, Székesfehérvár, Kisszeben, Lőcse and Szakolca.

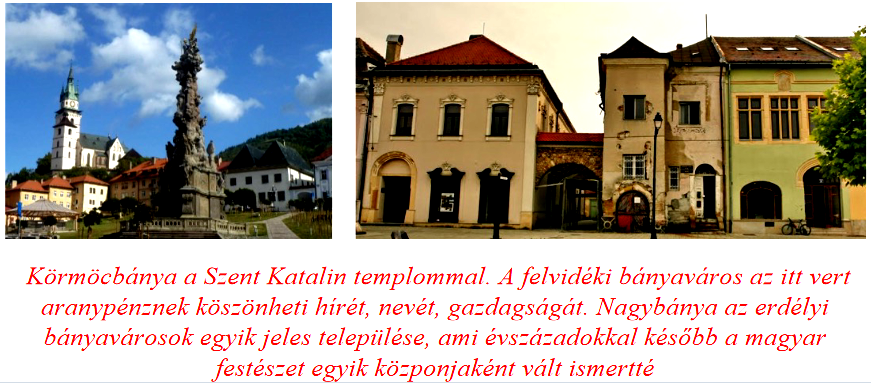

Special mention should be made of the mining towns that developed in the Felvidék, where rich silver and gold mines were located. The well-to-do Saxon towns in Transylvania, which often also developed from mining and handicrafts, had a similar legal status. It should be noted that the ancestors of the Saxons of Transylvania, the boots of the Highlands and the miners of Garamvölgy did not have the same historical background, but they came from German soil. The best-known such settlements are Körmöcbánya, Selmecbánya, Besztercebánya, Breznóbánya and nearly a dozen similar towns with special rights. In Transylvania, Nagybánya, Aranyosbánya and Zalatna developed the best, led by Szeben, where the royal judge ruled.

Körmöcbánya with St. Catherine's Church. The mining town in the highlands owes its fame, name and wealth to the gold coins minted here. Nagybánya is one of the famous mining towns in Transylvania, which centuries later became known as one of the centers of Hungarian painting.

Author: Ferenc Bánhegyi

The parts of the series published so far can be read here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28.