Characteristic (from the point of view of accountability) is the fate of the agents involved in the work of the secret services, the so-called Division III, and their removal from public life.

What happened here, compared to the Czech and German examples? Already in the fall of 1990, the largest opposition party, the SZDSZ, suggested that everyone who worked in any department of the III department should leave public life, and a law should be passed for this. The Demszky-Hack bill became a law only in 1994, long after the system-changing mood had passed, and so it is not at all a coincidence that the adopted law essentially did not mean much anymore, and became a bit of a laughing stock. This law only covered class III/III, i.e. internal countermeasures , it did not affect intelligence, counterintelligence and military countermeasures.

In addition, and especially in the case of this strange involvement, the law did not have any legal consequences, unlike, for example, the Czech lustration law. This meant the following: so-called vetting courts examine certain persons holding public positions, and if they find involvement, without the public's knowledge (!) they call on the person to resign. If you don't do this online, the data related to you will be made public as a kind of punishment. That's it. The ineffectiveness of the law led to quite comical things, since when Gyula Horn became prime minister in 1994 - Horn was one of the important leaders of the previous system - and the court called on him to resign, he just waved his hand and responded with a then-famous slang: so what? Ironically, he was right...

screenshot: YouTube

József Antall and his government therefore did not want to act meaningfully in the matter of elite exchange and accountability as a result of a kind of peculiar, in my opinion, misinterpreted "law-respecting" behavior. However, they also had another consideration that should be mentioned. And this is a kind of political situation assessment, which started from the fact that the regime change, democratization is actually still in danger, we still have to be very careful with the communist elite. (What József Antall himself told about an experience is typical: in 1991, they went to Moscow for a series of meetings of the member states of the Warsaw Pact with the plan that they would propose the dissolution of the organization. Antall said that after the announcement, they were not sure , that they can return home to Hungary alive... This tells a lot about their mental state at that time.)

They believed that achieving the results achieved up to that point is a big enough thing, and whoever wants to go beyond that is playing with fire. László Kövér , as an active contemporary actor, evaluated this in a 2004 presentation as follows: "The new, democratic elite, with József Antall at the head, perhaps even in view of the Russian troops staying here, sees the main threat to democracy as a possible orthodox-communist restoration he saw in an experiment, to avoid which the so-called he looked for a potential ally in the reform communists already in the transition process. Kádár system was well underway with the participation of the free democrats ."

An aspect, at least as important, that was already mentioned in the previous quote should be mentioned here. And this is the turn of the Association of Free Democrats. The initially regime-changing and anti-communist party gradually began to approach the Socialist Party after the Antall government came to power and finally entered into a government coalition with it in 1994 despite the fact that the Socialists alone had a calm government majority.

This turn of the Free Democrats actually became completely clear in 1992, but already in the autumn of 1990 they turned against their former opposition partner, the MDF, and the government. This was explained to the public by the fact that the Antall government, mainly István Csurka - who was already kicked out of the MDF in 1993 and then formed the radical Hungarian Justice and Life Party - increasingly moved towards the extreme right, "became fascist ”, endangering the young Hungarian democracy. In fact, this justification was not entirely, or at least not in all its elements, tenable, since after the removal of István Csurka and the radical right-wingers, and despite the clear moderation of József Antall, the rapprochement did not happen again.

They knew, yet they dared to do it - they entered the post-communist government

In this regard, it is more about the fact that the sovereignist, conservative politics based on strong national foundations was much more distant from the free democrats than the post-communist, but still internationalist, cosmopolitan leftism of the socialists , with which they had more to do as left-liberals than national conservatism. Thus, they "changed" the fault line, instead of the anti-communist-successor party (post-communist) opposition, from then on they positioned themselves on the national versus cosmopolitan-globalist fault line.

It followed from all of this that the SZDSZ was very sharply opposed to the efforts of the Antall government from the autumn of 1990, including its very rare and exceptional intentions of accountability towards some members of the nomenclature. And since the SZDSZ had a very good intellectual-social scientist and media background then and later, with the understandable support of the socialist party in the background, they created a strongly opposing public atmosphere around these very isolated experiments.

Mária Schmidt gave a highly critical interpretation of this phenomenon "The left-wing liberal intellectual elite and their political representation, the SZDSZ, are largely responsible for the fact that we missed the historic chance for the country's moral renewal. Using their moral capital acquired in the democratic opposition, they released the successor party of the MSZMP from quarantine after barely two years, and after their overwhelming election victory, they undertook co-governance.

Author: Tamás Fricz, political scientist

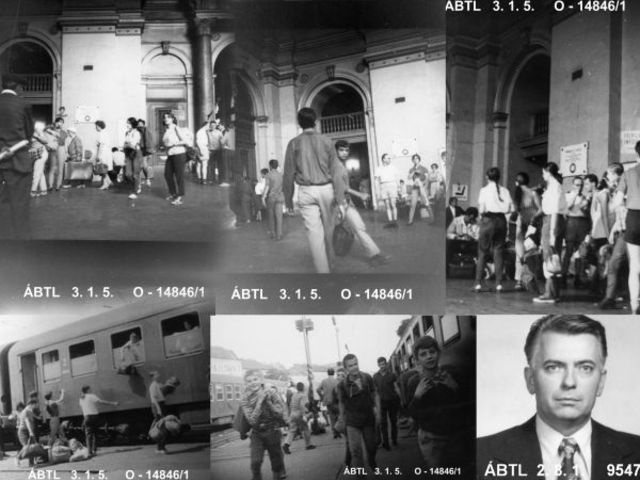

(Cover image source: III/III chronicle blog)

To be continued