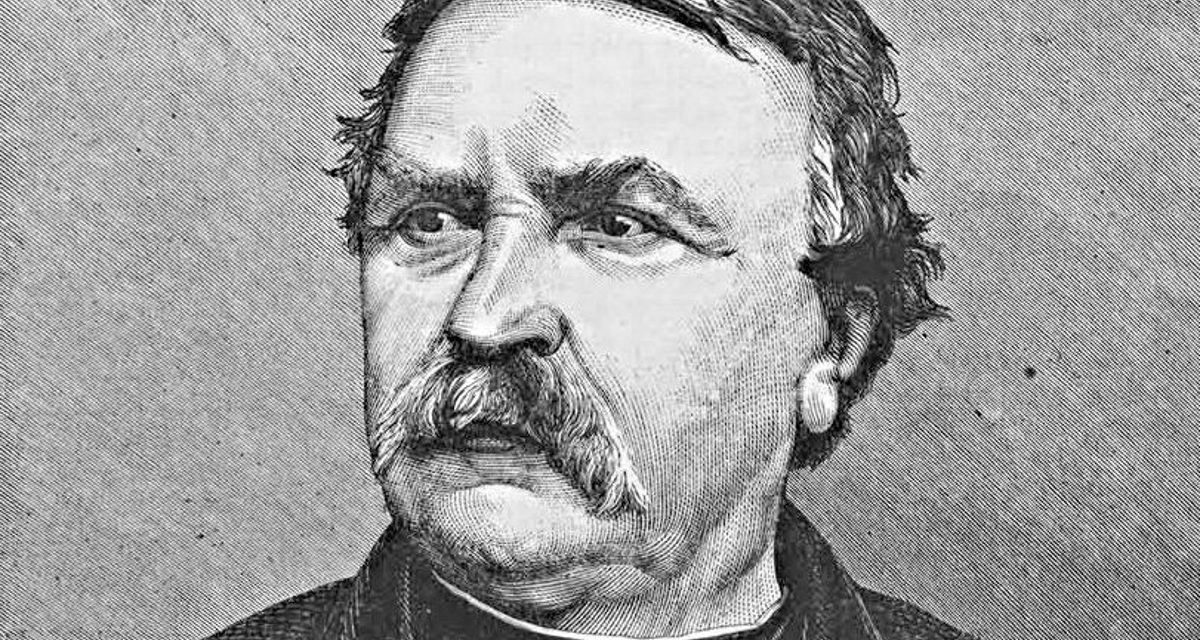

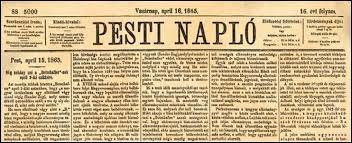

Ferenc Deák's political career is still an unavoidable point of reference for the Hungarian political and scientific elite. Through compromise, his life's work has become a symbol of reasonable compromises, especially during the last quarter of a century. On April 16, 1865, one of the most important symbolic milestones of Ferenc Deák's political career and the political path to reconciliation, the Easter article, was published in Pesti Naplo.

After the defeat of the war of independence in 1848-49, a period of bloody retaliation followed , which ended only in 1850, with the dismissal of Field Marshal Julius von Haynau. The young emperor, Ferenc József I, then wanted to merge the defeated Hungary into the unified Habsburg Empire using absolutist methods.

In the years known as the Bach era after the Minister of the Interior, Alexander Bach, the old constitution of Hungary, which "played its rights with an armed uprising", was repealed, its traditional administrative system was abolished, and the country was divided into five districts. Although Bach dressed his officials in Hungarian regalia in order to gain the trust of the Hungarians, the people only mocked them as Bach hussars, and the country responded with passive resistance. The emperor also felt the unsustainability of the system, and in 1859, on the pretext of the military defeat suffered in Italy, he replaced Bach.

The monarch signaled his intention to change with the October diploma issued in 1860 and the February 1861 patent, and also offered a more liberal imperial constitution. In 1861, he convened the parliament so that Hungarian representatives could also take a seat in the planned imperial assembly, the Reichsrat. Unwilling to give up the country's independence, the Hungarian political elite - after a long political struggle - rejected the emperor's draft constitution in a letter (the more radical wanted to do this in a resolution), stating:

they do not budge from the principles of 1848.

József Ferenc responded by dissolving the parliament on August 22, 1861, and installed Minister of State Anton Schmerling in power. Schmerling would have been willing to make reforms, but not to recognize Hungary's special position in the empire.

During the transitional period known as the Schmerling Provisional, behind the scenes - mainly with the participation of Hungarian conservatives - negotiations with the Vienna court were already underway: the 1867 solution, which included a separate parliament, joint military affairs, foreign affairs and finance, had already been proposed years earlier by the former chancellor, Count György Apponyi and Count Emil Dessewffy, president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Deák returned to politics at the beginning of 1865. "Procator of the Nation" essentially revived Dessewffy's previous ideas, "Additions to Hungarian Public Law " he indicated that the Hungarian liberals were ready for negotiations. József Ferenc was also inclined to compromise, and he sent Baron Anton von Augusz to Pest several times in the spring of the year, and Deák then explained his position in detail in the famous "Easter article".

Deák penned an unsigned article on the front page of the April 16, 1865 issue of Pesti Napló to journalist Ferenc Salamon in the Angol Királynő Szálló the day before. The purpose of the dictation was that even his handwriting could not be recognized in the editorial office.

Deák wanted to respond to what was written in the April 9th issue of the Vienna newspaper Botschafter, which is the mouthpiece of the Minister of State Anton von Schmerling, which, reviving the theory of "abuse of the law", accused the Hungarians of having separatism as their essence, and a completely senseless "separation desire" in their history ( Sonder- Zug) marches along", passing down from generation to generation.

The main thread of Deák's Easter article and also his reply was the examination of the causes and goals of the "separating desire". In Deák's interpretation, there was also a desire to separate, which was aimed at protecting the Hungarian constitution and against attempts at assimilation:

"If under this distinguishing desire the "B." it means that the Hungarian nation has always faithfully adhered to its own constitutional independence, and has always shown a strong antipathy to the authorities, and even more so to the efforts of some of the administrators of the authorities, which were aimed at ignoring or even destroying Hungary's constitution, and to some extent at merging the country, there is no reason to contradict "B." quoted lines."

Deák stated that Hungary has always resisted and will continue to resist assimilation attempts, but this centuries-old peculiarity should not be equated with efforts for ultimate secession. He called the claim that the Hungarian political elite did not want to cooperate with the Habsburg dynasty and that it was incapable of compromises untrue.

As he wrote:

"So one goal is the solid existence of the empire, which we do not wish to subordinate to any other considerations. Another goal is the maintenance of Hungary's constitutional existence, rights, and laws, which are also solemnly guaranteed by the sanctio pragmatica, and from which to take more than what is required to ensure the firm existence of the empire would be neither right nor expedient."

He felt that the Hungarian nobility was also willing to revise the laws of 1848 in order to reach an agreement:

"We will be ready at all times to bring our own laws into harmony with the certainty of the firm existence of the empire by means of legislation."

The "Easter article" indicated that Deák and his circle were willing to establish a real union relationship with the empire. Francis József soon dismissed Schmerling and the now open negotiations began, which accelerated after the Prussian-Austrian War of 1866, which ended in Austrian defeat, and the loss of Venice. These discussions led to the settlement, the creation of the Austro-Hungarian dualist state, the XII of 1867. for the creation of a legal article.

The afterlife of the Easter article is no less interesting than its content and the circumstances of its birth. Over the past hundred and fifty years, it has been recalled many times and by many people, placing it in the context of their own age.

The person of Ferenc Deák is a recognized part of Hungarian political culture , all political groupings relate to him in some form. His thoughts extracted from his various works echo in his speeches and publicisms of the last twenty-five years at least as often as thoughts from István Széchenyi or István Bibó.

The Easter article is moderate, but also imposing, and its guidelines are unmistakable.

Featured image: Wikiédia