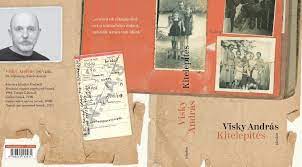

András Visky presented one of the most important works of recent years.

The experience of displacement does not refer to the past, but to the present - this was said by the writer and dramatist András Visky at the Cluj-Napoca presentation of his novel entitled Displacement, published by Jelenkor publishing house (the entire conversation, in which Visky's interlocutors were Dóra Mărcuțiu-Rácz and Gábor Tompa, can be viewed at this link ). The statement may seem surprising at first, but it becomes understandable as soon as it becomes clear what he means: the sight of Ukrainian refugees forced to leave their country because of the war, whom he met in several places, for example in the congregation of his brother, a reformed minister:

"I saw these young mothers with children running around them, but they were happy."

It is precisely this, the child's point of view, that connects the current displacement experience with the past. András Visky was barely two years old when his father, the reformed pastor Ferenc Visky, a highly respected figure in the "revival movement" within the church, Bethania, was sentenced to 22 years in prison by the Romanian communist government as part of the wave of reprisals after 1956. He himself, along with his six siblings, their mother, and their governess, who voluntarily undertook the exile

he was placed in a forced residence ("déó", i.e. domicilia obligatorio) in the Bărăgani lager world,

where they were able to take a Károli Bible with them as their only "possession", thanks to a coincidence (or rather, Accident?).

The years they spent there - they were released after more than four years, but because they had nowhere to go, they stayed for a while - proved to be decisive in terms of Visky's creative career, and looking back, it may seem as if the magnum opus, which has just been published, is almost all of his writing and theater work to date. it would gravitate towards Displacement.

The Lătești camp, where he spent a significant part of his childhood, was living history itself:

The extremely colorful panopticon of the barrack world from the point of view of ideology and worldview was populated by characters from the anti-communist intellectual milieu of the era, such as the widows of Marshal Antonescu and Iron Guard leader Zelea Codreanu, humanities scholar Nicolae Balotă, literary scholar Adrian Marino, Paul Goma, the later dissident writer, Nadia Russo, the Russian a female pilot, priests, scribes, Jews, Romanians, Hungarians and, of course, the ubiquitous informers - little András Visky, the youngest of seven brothers, grew up among them.

Could this childhood have been happy?

Famine, frost, privation, humiliations, indescribable living conditions, diseases, insecurity, vulnerability, lack of a father, everyday encounter with suffering and death - these characteristics do not fit into the textbook definition of "happy childhood". The Expulsion does not become a story of personal and family suffering: Visky's darkest passages and seriously meandering sentences are permeated by some kind of (almost out of this world) serene wonder of the child who finds himself at home in the camp at the world in which he is given to live - and the gentle irony of the adult who recalls it, who, paradoxically, is able to condense the experience of captivity into an experience of freedom.

Speaking of passages: the structure of the novel follows that of a biblical poem, with numbered episodes running one after the other (822 in number), in long sentences, without a capital letter or a period at the end of the sentence - indicating that (as Visky put it) it is all part of a big story that it didn't start with him and it doesn't end with him.

This story continues the biblical narrative in a profane way:

that - miraculously? accidentally? - preserved his Holy Scriptures, whose God for the outcast Visky family is not the distant and unapproachable Lord, but the family member who walks among them every day, who exists with the certainty and naturalness of breathing, with whom one can joke, grow old, argue, and talk, and whose occasional absence also draws attention to its existence. Because sometimes it disappears so much that perhaps you don't even believe in yourself: "If anyone, God must be an atheist." And sometimes he is foreign and even has a speech impediment, since he speaks to them in the old, outdated language of the Charles Bible, which is incomprehensible to the children, so they decide to teach him "modern Hungarian". For Visky, God is not a matter of faith, but of presence; as he said at the book launch in Cluj:

"I don't believe in God because I met him."

Source: Facebook

András Visky's work is the pinnacle of Hungarian literature born in Transylvania in recent years, and it is a long-lasting reading experience. Father's and mother's novel in one, gulag novel, testimony, coming-of-age story. Which even allows itself to dissect questions such as who owns Transylvania. Here is passage 757:

"to whom does Transylvania belong, to whom does it belong, the rhetorical question was heard even from the church pulpit, and to freely discuss Transylvania from the pulpit in itself seemed like a sane undertaking in the eyes of the serial oppressors and progressives of all time, who says that I would freely discuss it, asked our pretended Father with astonishment from the terrified doubters, who is free here, and if we are not free, we have nothing to lose, why would we be silent about him, our Father continued with growing momentum, if this is the question, then we must talk about it"

This is Displacement: talk about what can't be talked about.