Religious tales should be interpreted like parables - believes József Péter Bálint, Attila Prize-winning author, university professor, literary critic, fairy tale researcher, whose two important study volumes were published this year by the Magyar Napló–Írott Szó Alapítvány. A selection of the author's academic writings published in the past decade entitled "Fairy Interpretations" published for the holiday book week, while "Jesus Patterns in Folktales" is a monograph that fills in gaps. Péter Bálint presents his volume to the Magyar Nemzet.

– Coincidentally, sixteen studies can be read in both volumes. The first study volume, Interpretations of Fairy Tales, published this summer, is a selection of writings from the past decade, which was prepared by my daughter, folklorist Zsuzsa Bálint, from nearly fifty texts. The second, Jesus Patterns in Folktales, is an independent monograph and the result of the past three years. I approach magic tales not primarily from theological or literary aspects, but from many other aspects: folkloristic, historical, philosophical. I investigated the main biblical stories and motifs that appear in these texts, and I thought I discovered many similarities between the heroes of the stories and the life, activities, and teachings of Jesus. The work was complex: on the one hand, I compared fairy tales with ancient religious texts, Jewish sources, and medieval documents, and on the other hand, during the analysis, I applied all the ethnographic and religious knowledge that I had acquired as a literary scholar in the past decades.

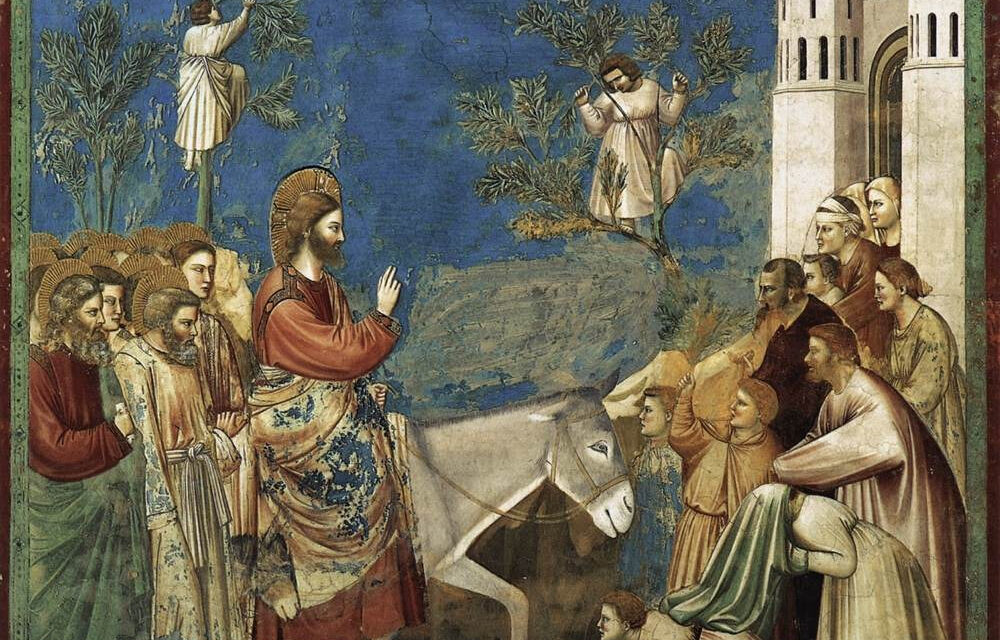

First of all, it is worth highlighting that this demonstrable similarity reflects the fact that the peasant was able to transfer certain topics from the biblical stories he heard during the sermon in the church into his own thinking, into the texts he created himself. For example, miraculous birth, hidden childhood, and teaching appear. But we can find not only similar features to Jesus, but also many moments when the peasant misinterprets Jesus' speeches and activities. Among others, this is the case of miraculous healing, Jesus does not appear as a miracle doctor in the religious text. We can see that in the world imagined by the storyteller, the magicians who perform miraculous healing are the ones who behave just like Jesus, the peasant mostly imagines himself as a teacher, miracle worker, preferably a rabbi or even a magician. It soon became clear to me that many more Jesus patterns can be identified in folk tales, as was done, for example, by the American folklorist Alan Dundes, who hypothesized two or three such features in parallel with the mythical heroes. Reflecting on his research, I discovered several contradictions. One such topic that is also debated in theology is whether Jesus descended into hell or not.

But it is also interesting to see the difference that, while some fairy-tale heroes draw swords, we know that Jesus does not.

Storytelling is an extremely lively genre, where students are not passive but active participants in the event. Sometimes the participants interrupt, sing or even dance. The saying is actually a performance, where the fabric of the story told by the storyteller - who has extremely colorful and complex knowledge - is constantly changing depending on the community of those present. The storyteller himself knows the problems of the peasant, so he weaves these individual experiences into the stories. Each of these stories lasts up to five, six or more hours. When the means of mass communication became widespread in families - the radio, and later the television - the long fairy tales soon became shorter, as people had different needs, and thus their relationship to the fairy tales also changed: they lost their credibility and validity.

Source and full article: Magyar Nemzet

Featured image: Magyar Kurír