After a short break, we continue the series that was originally published on the PestiSrácok portal. The author, Zsuzsanna Borvendég, is a historian, and her subject is, of course, uncovering the crimes of the dark communist past. Among our readers, there are certainly those who missed the original series, but those who did not get to know all the episodes should also read it again. Knowing the whole picture, can we understand how we got here?

The Prague Spring

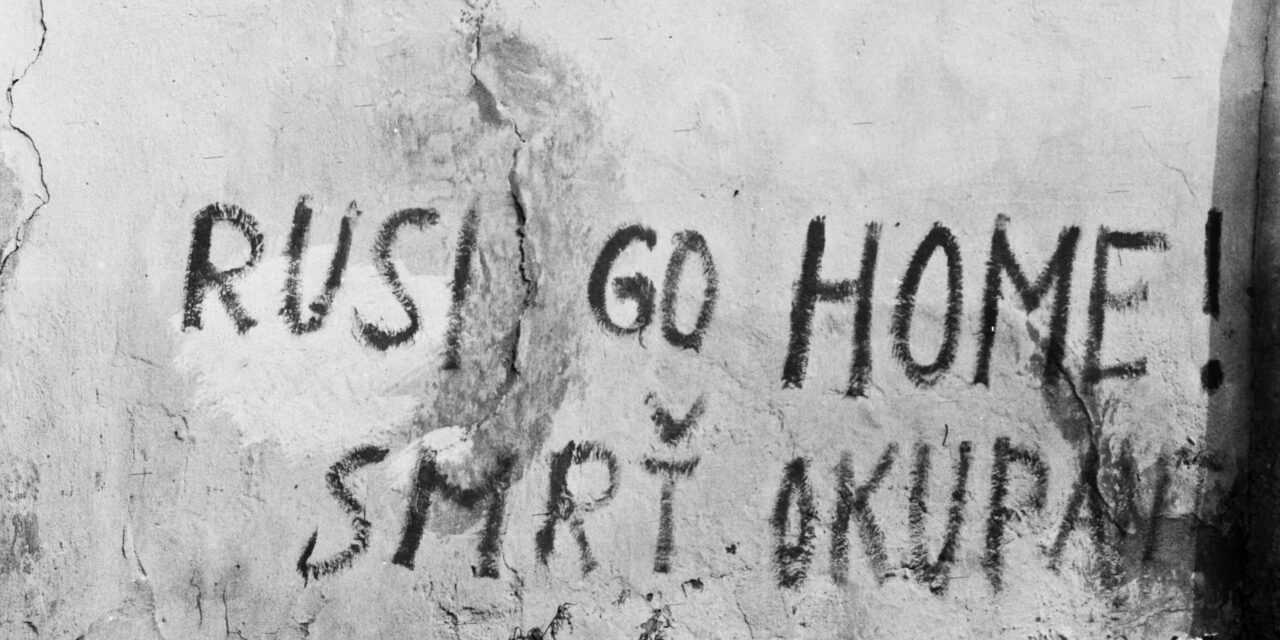

From 1968, the first thing that comes to mind for most of us is the march in Prague. Kádár fulfilled the Soviet order without question or doubt and directed the Hungarian soldiers against our neighbors, while the majority of Hungarians watched the news with a clenched stomach, since not long before we also experienced how our freedom was trampled into the mud by the merciless tracks. However, few people know that Hungary not only provided military aid to the invaders, but also did a lot of political background work to ensure that the Soviet-type system remained solid in Czechoslovakia.

Norbert Siklósi appeared several times in the series , the dark affairs of his press empire, the exciting stories of the intertwining of the communist secret service and the media. /…/ As a gray eminence, Siklósi controlled domestic journalism, deciding over destinies and existences. He turned from a merciless "order maker" into a benevolent and generous power, who provided a living after the establishment of the consolidation and thus obliged those journalists whom he had previously pushed to the coast. He learned how to deal with "troublemakers", how to suppress critical expressions of literate people, and he used his knowledge not only in our country.

Pull it - loosen it

Previously, you could read that as secretary general of the MÚOSZ, Siklósi worked in close cooperation with one of the KGB's cover institutions, the International Organization of Journalists (NÚSZ), and he was also its treasurer from 1966. The headquarters of NÚSZ operated in Prague, so Siklósi had to be in daily contact with Czechoslovak journalists. Czech politicians advocating significant liberalization expected advice from Siklósi, who had considerable experience in the field of press management, and thought that the relative freedom of the Kádár consolidation could serve as an example for them as well. They forgot only one thing: in Hungary, the easing was preceded by a cruel repression, that is, there was something to take back, there was something to let go.

In March 1968, Siklósi negotiated with the head of the Information Department of the Czechoslovak Ministry of Culture and Information in Prague, who considered Hungarian press management to be authoritative. During their conversation, they indicated that they would be interested in the practical side of Kádár's cultural policy, and would like to learn more about how the self-censorship based on the editor-in-chief's briefings works in our country. However, the military intervention in August brought the reforms in Prague to a standstill, the aggression of the Warsaw Pact member states was a clear message from Moscow to the Czech press as well: the relative freedom of Czechoslovak newspapers in the six months before the intervention, and the careful but clear formulation of criticism of the system was unacceptable to the Soviet leadership . Siklósi also confirmed this message when he was the first representative of the Hungarian press control to travel to Prague after the occupation.

The anointed defenders of press freedom

After 1956, Siklósi already conducted a member review within the ranks of MÚOSZ, setting aside everyone whose even a single suspicious sentence appeared in print for years. Then, among the disciplined journalists, those who were willing to fall in line, he slowly let them back into the newsrooms. He definitely marked the room for movement, everyone knew where the boundaries were and could also experience what happens if they cross them. After such antecedents, it was only possible to realize the peculiar atmosphere of press censorship, the irrational reality of "there is a bald censor sitting in my brain".

Even after the military intervention, the colleagues in Prague considered the Hungarian system as an example, but Siklósi urged them to be patient: he drew attention to the fact that they were not guided by the Hungarian conditions of 1968, but by those of 1957. If they have already managed to silence the voices of the opposition, to "cleanse" the Czechoslovak journalist community, or at least intimidate them enough to make them unconditional servants of the system, then they can consider the current situation in Hungary as an example.

A few decades later, during and after the Velvet Revolution, NÚSZ came under serious attack for not standing up for Czechoslovak journalists after the occupation. We can see that the organization was not merely silent, but did the exact opposite of what an interest protection body committed to freedom of speech should have done.

image source: PestiSrácok

In May 1969, just at the time when the retorts against journalists began in Czechoslovakia, the NÚSZ Executive Committee held its regular session in Balatonszéplak. We know from an agent's report that the session consisted of the reading of pre-written speeches; the organizers made sure that there was no accidental discussion between the attendees. According to the state security report, the journalists from Austria protested that Siklósi "forced them with fire and iron" so that they would not touch on the situation in Czechoslovakia in their speech. The session itself brought little meaningful work, but more fun, bathing in the Balaton and representative luxury, which caused displeasure for the participants as well.

Spies in Prague

Another important episode related to the entry into Prague should be mentioned, in the background of which the NÚSZ should also be sought. In August 1968, Hungarian intelligence deployed agents in Prague to assist the Hungarian foreign mission there in obtaining information. In itself, this fact is less attention-grabbing, since in the given political situation, which can be said to be critical, it is understandable that the government of the neighboring country needs the information first hand. However, it is more surprising - at least on first reading - that the choice fell on Péter Szolnok, the officer of the press supervision residency of the Intelligence Service.

Péter Szolnok was not a small-field player. He joined the staff of the ÁVO in 1947, first working in mail control and then in the Central Anti-Corruption Department. In 1950, he was entrusted with the leadership of the American countermeasures division. In 1953, he went to study in the Soviet Union for a year, and after his training, he was assigned to several foreign stations. In 1955, he was entrusted with the management of the residency in London, where he served until 1960. In 1964, he was commissioned to organize the intelligence residency in Rio de Janeiro, from which he returned in 1966. He then joined the MÚOSZ as a top secret staff. From 1967, he was an SZT officer within the ranks of the MÚOSZ, and after the organization of the Press Residency, he became the first head of the secret service press supervision. His autobiography reveals why he was the first to be sent to Prague by the intelligence service almost immediately after the intervention: because

"approx. for two years I had an intensive working relationship with the International Organization of Journalists based in Prague, I knew all its functionaries personally".

We know that the intelligence services of the countries of the Soviet bloc worked in a division of labor, so the fact that an officer serving in the media field was sent from our country to Prague after the Prague Spring was stolen can be a good indication. In the International Organization of Journalists, as one of the front organizations of the Soviet secret service, the Hungarian member organization was one of the most active. This is how the fact that Siklósi and Szolnok traveled to the Czech capital almost immediately after enlistment becomes understandable and takes on significance. Szolnok's statement - that

We were the first civilians after the enlistment

- and the fact that Siklósi also arrived in Prague soon proves that the instructions of the NÚSZ - indirectly the Soviet secret service - were carried out in the capital of the occupied country. In this way, Szolnok's diplomatic scandal-causing activities also become understandable, as he tried to recruit the fugitive editor-in-chief Oldřich Švestka and Rudolf Barák, the former interior minister of Czechoslovakia, to the Hungarian embassy without the instructions and permission of his superior in Hungary. After the scandalous "individual" action, Szolnok was given a warning, but he managed the Press Residency until September 1971.

Anyway, Szolnok later remained a member of Siklósi's network-like network of contacts, since on the eve of the system change he was part of the management of the subsidiary company Interedition, which he had already met in the previous parts and which was used in the asset rescue.

Source: PestiSrácok

Author: Borvendég Zsuzsanna

Cover image: Fortepan archive