During the regime changes in Eastern and Central Europe, a very marked atmosphere of accountability and accountability prevailed in the region towards the former communist leaders. On the basis of this Zeitgeist, a series of measures were taken in several countries that relegated the obviously responsible actors of the former system to the background and removed them from public life. (For example, the disclosure of the Stasi files in Germany, the lustration law in the Czech Republic, etc.) These measures clearly limited and prevented the former elite from staying together and the network from becoming stronger again.

Of course, even then, and even today, many people ask the question - especially strongly in Hungary - whether revenge against the former elite and nomenclature can be justified, which may not always have a legal basis, moreover, the former communists eventually ceded power through peaceful negotiations, so they have merits, why should they be mowed down?

Well, I guess a clear revenge campaign, "crucifixion" would not have made sense. But I believe that a kind of moral accountability and the suppression of those with obvious responsibility from public life was morally and politically justified - and would have been justified in the case of Hungary. Let's not forget that here, if not revolutions - since they took place peacefully -, revolutionary changes took place with the fall of dictatorships and the establishment of democracies. However, it is difficult for people to prove that real changes have taken place if the people who were at the head of a basically dictatorial system remain in leading or influential positions in the new system, the democracy. It is therefore an everyday moral expectation, if you like, that those who governed an unjust system should not govern a just system, because if this happens anyway, then the significance of the regime change will vanish.

On the other hand, the unchanged presence of the old elite cannot be justified from a rational political point of view. Not because the members of this elite were socialized in the dictatorship, they learned its management methods, the reflexes of the dictatorship were fixed in them. However, if they regain political and governmental power, doubts may arise as to whether they really always represent the interests of their own country in the best and most effective way and whether they do not bow again and again to the expectations of the new great powers. Of course , a person can always be assumed to be able to change, but if the power center and network remain together, it has a completely different significance and degree of danger.

it would have been justified both from the point of view of the consolidation of democracy, for moral and political reasons, and also for rational considerations, , around 1990-1992. In addition, the people and society would not have shied away from this either, even in spite of the fact that they observed the events of the regime change with a rather great passivity.

In 1991, Rudolf Tőkés referred to a survey of August 1990, according to which 51 percent of people believed that the regime change did not happen in their environment either, and they are waiting for those responsible for the past four decades to be held accountable. But that didn't happen; the Antall government essentially did not hurt or touch the elite of the former dictatorial order. Körösényi writes that the public administration apparatus was preserved during the regime change, and there was no real change of personnel here either (!).

It is worth quoting here a bit longer from a study by József Bayer, who was otherwise clearly left-leaning, who comments on the processes with no small surprise (he was fundamentally opposed to the exchange of elites and accountability, which is also clear from the text): "This fear (that is, of accountability and the fear of elite change - FT) was ultimately not confirmed by the period since the change of power. There are no widespread political witch hunts, no political show trials, bloody showdowns and the like. There are, of course, petty compliances, the exchange of elites often takes place with hard-to-justify priorities, and we encounter intolerant, denouncing and exclusionary expressions. But the basis of the anti-communist hysteria still remained as an ideological side effect of the regime change, which - after the mobilizing political energies that could be gained from it had dried up with the change of power - seems to be subsiding more and more." He wrote this in early 1991!

It is part of the facts that there was an attempt at accountability during the decisive phase of the regime change period. was formulated by a political circle within the MDF ( Imre Kónya holding its elites and officials accountable. But this idea also failed, mainly because the MDF center, the government's general staff and József Antall himself did not undertake these steps.

The consequence of all this is that the old elite was only temporarily relegated to the background - only partially until then - in order to return stronger in 1993-1994 and win 54 percent of the mandates, i.e. an absolute majority in the parliament in 1994.

Author: Tamás Fricz

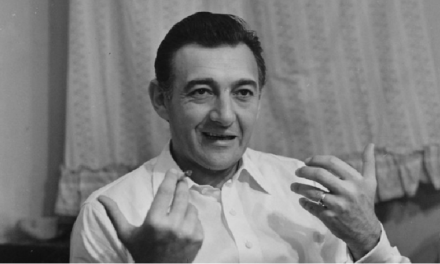

(Cover photo: MTI/László Varga)