"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated.

A hundred years that caused the deterioration of Hungary

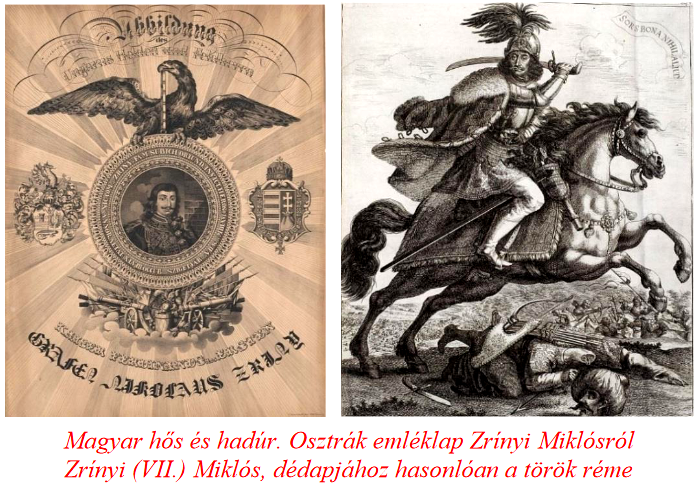

The great-grandfather gave his life for his country in 1566, and the great-grandson Miklós Zrínyi in 1664. They were both killed. The great-grandfather is in the Turkish open battle, the great-grandson is stolen by the Habsburgs, disguised as a hunting accident. The events of Hungary, which was divided into three parts, were discussed in more detail in the previous sections. In part 40, the birth of the Principality of Transylvania, in part 41, Life in the Kingdom of Hungary, and in part 42, the brief overviews entitled The History of the Turkish Subjugation touch on the era of the three countries of the Carpathian Basin, when the prominent figures of the Zrínyi family fought for the survival of Hungary and at the same time they fought for the defense of Europe.

It must be seen how geographic location, political and economic interests, and religious affiliation have divided the once united Kingdom of Hungary.

After all, Transylvania and the eastern areas of the country fell under the sphere of interest of the Ottoman Empire, while the western and highland parts of the country were controlled by the Habsburg Empire. When Miklós Zrínyi, Szigetvár castle captain and Hungarian lord, was organizing campaigns against the Turks, György Fráter and his followers were working on the organization of the Principality of Transylvania in those years. In the meantime, the rulers of the two great powers - Süleyman the Great and Ferdinand I of Habsburg - made our country a battlefield, destroying and looting its territory and economic treasures wherever they could. The situation has not changed even after a century. The fact that Hungary still existed at all is due to the ancient Hungarian virtue, the policy of never giving up. When the general, politician and poet Miklós Zrínyi defeated the Turks in the winter campaign of 1664 in battles celebrated throughout Europe, Mihály I. Apafi, who sat on the princely throne for nearly three decades, consolidated the independence of Transylvania. Let's add, with Turkish support. It was founded by the Báthoryaks, István Bocskai, Gábor Bethlen, the Rákócziaks and the other "neck Calvinist" Hungarian lords. However, Hungarian virtue was shown not only in Protestants, but also in those who lived in the Roman Catholic faith. After all, Miklós Zrínyi is the one who, following his ancestors, remained loyal to Vienna, fueled, among other things, by the implacable fight against the Turks. However, when he had to choose between Vienna and his Hungarian homeland, he chose the latter. (The "killer wild boar" came right away!)

Count Miklós Zrínyi

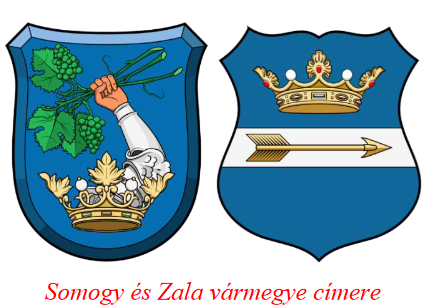

His great-grandson, born in Csáktornya in 1620, also had a Croatian name (Nikola Zrinski), despite the fact that he was already born to a Hungarian lord. The nobleman with a large estate has already inherited the titles of royal councilor, master of the horse, Croatian ban, hereditary lord of the counties of Somogy and Zala, and captain-in-chief of Légrád, which were created for him by his ancestors.

The father, György Zrínyi, is Croatian, and the mother is Magdolna Széchy.

The father, György Zrínyi, is Croatian, and the mother is Magdolna Széchy.

When the mother gave birth to her second son, Péter, in 1621, she died of puerperal fever. Five years later, in 1626, the two sons, Miklós and Péter, also lost their father. The two orphans Habsburg II. They came under the guardianship of Ferdinand, who sent them to the Németújvár estate of their father's cousin, Count Ferenc Batthyány. Here, the count's wife of Austrian-Czech descent, Éva Lobkowitz-Poppel, raised the two boys. Instead of their mother, it was their mother who surrounded the Zrínyi orphans with love. In the meantime, however, the Zrínyi fortune dwindled, so the king terminated the guardianship and entrusted their education to Péter Pázmány. (It should be noted that the two boys had five guardians after the father's death.) The Zrínyi boys graduated from Jesuit schools in Graz, Vienna and Nagyszombat. Following the custom of the time, Miklós and Péter took a cruise in Italy between 1635-1637, which had a significant impact on their development. While they were constantly fighting against the Turks - this was also part of the family tradition - they became highly educated sons of the Baroque era. Miklós' court in Csáktornya became one of the centers of intellectual and political life. Miklós set up a library (Bibliotheca Zriniana) that is also significant on a European scale - perhaps the example of King Matthias played a role in this. Among the works bought mainly from Venice, books on historical subjects played a role. In addition to Hungarian and Croatian, they also spoke Italian, Latin, German and Turkish.

After finishing school and traveling to Italy, 27-year-old Miklós and 26-year-old Péter took over the family estates.

Miklós stayed in Muraköz, Péter owned, among other things, the seaside ports. Both the sea ports and the cattle driving routes through Muraköz brought considerable income to the Zrínyi people. The agricultural products delivered to Western European markets, as well as the textile and exotic goods arriving from there, increased the family's wealth with a substantial profit. We can confidently say that the members of the Zrínyi family knew not only warfare, politics, and the arts, but also trade, as the mentioned trade routes suggest one of the best organized networks of the era.

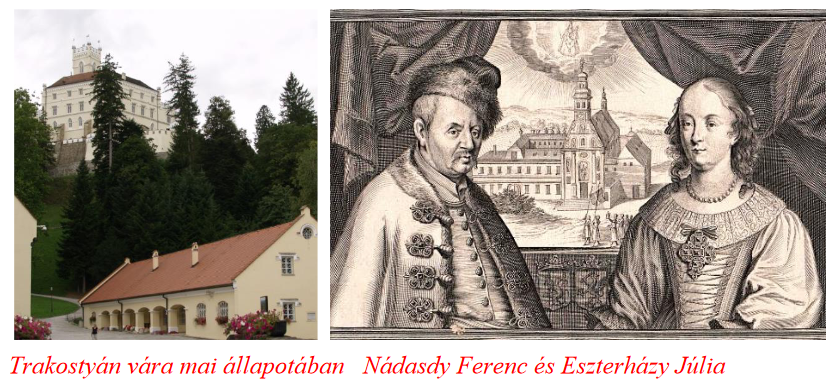

Family circumstances

We read the story of the rise of the Zrínyi family in the previous, 47th episode. The people of Zrín living in the 17th century represented the peak of the family's power and reputation. They set an example of Hungarian survival when they confronted the enemy attacking our nation and wanting to destroy the rest of Hungary as well. In particular, Miklós did a lot for the creation of an independent Hungary, who took his part in almost all areas of public life with superhuman work ethic and great activity. In the meantime, however, he did not neglect his family, because he knew that without descendants, everything he had built so far would be wasted. In 1646, he married the daughter of count Gáspár Draskovich, his old love and muse, Mária Euzébia. (Previously, he applied for the hand of Júlia Eszterházy, who, however, married Ferenc Nádasdy, the later country judge. These were the years when the twenty-year-old Zrínyi matured into a poet by writing his love poems. He calls Euzébia Viola in his poems.) Miklós Zrínyi inherited the villages of Trakostýán and Klenovlik, while his father-in-law therefore he paid HUF 30,000. However, his young wife died at the age of twenty, in 1650. The former father-in-law demanded the villages back, but did not want to return the money. This led to lengthy litigation.

Two years later, in 1652, Count Miklós married Baroness Mária Zsófia Löbl in Vienna. Four children were born from the marriage, but Borbála and Izsák died when they were small children. Katalin Zrínyi became a nun, and Ádám sought his livelihood on the battlefields. The boy died a heroic death in the battle of Sálánkemén in 1691, following the never-ending fight of the Zrín people against the Turks. Ádám Zrínyi, who trained as a military engineer, was only 29 years old.

Miklós Zrínyi already achieved significant military successes before founding his family. In the 1640s, however, he served the king not against the Turks, but against the Protestant wars. He participated in the Thirty Years' War /1618-1648/ with an army raised at his own expense, when he fought against the Swedes and their allies in Silesia. It should be noted that in the fall of 1644, in the Highlands, he fought against the Transylvanian prince György I. Rákóczi. More than three thousand people died in the bloody battle, in which the young Zrínyi distinguished himself with his heroism. As a reward, he was appointed General of Croatia. (It is a matter of fate in Hungarian history that in 1666, the grandson of the biblical prince, Ferenc Rákóczi I, married Ilona Zrínyi, the daughter of Miklós' brother, Péter.)

Military successes of Miklós Zrínyi

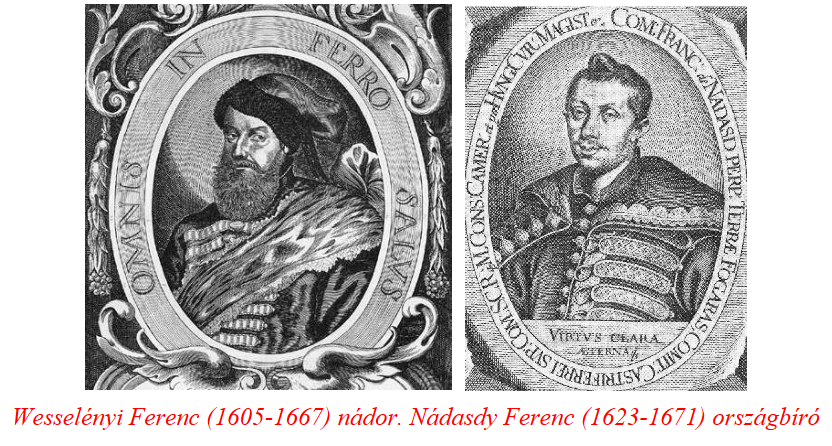

Except for the war against the Protestants, Zrínyi devoted all his energy to the wars against the Turks in the remaining two decades of his life. The victory in Légrád in 1647 also benefited his brother, Péter, who had previously been in open conflict with the Germans. After the war success, Vienna forgave Péter Zrínyi's hatred towards the Germans, which he felt against them because of the disturbance of his possessions. The 1650s passed with ceaseless warfare. It was then that it became clear to Zrínyi that the German mercenaries sent under his banner did not obey him, in fact they looted and destroyed the same as the Turks. During these years, the idea of organizing the "national party" was formulated in Zrínyi. Recognizing Zrínyi's goal, Vienna blocked his election as Palatine in 1655, and Ferenc Wesselényi won the important national office.

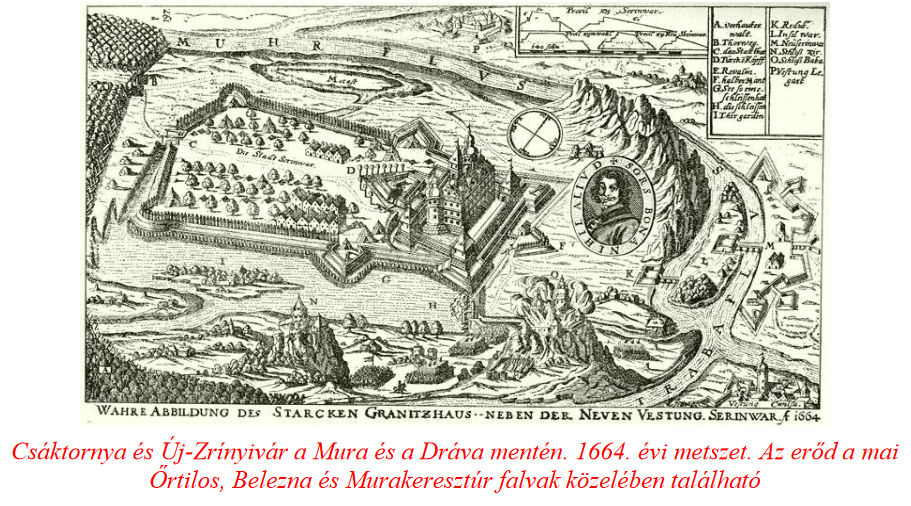

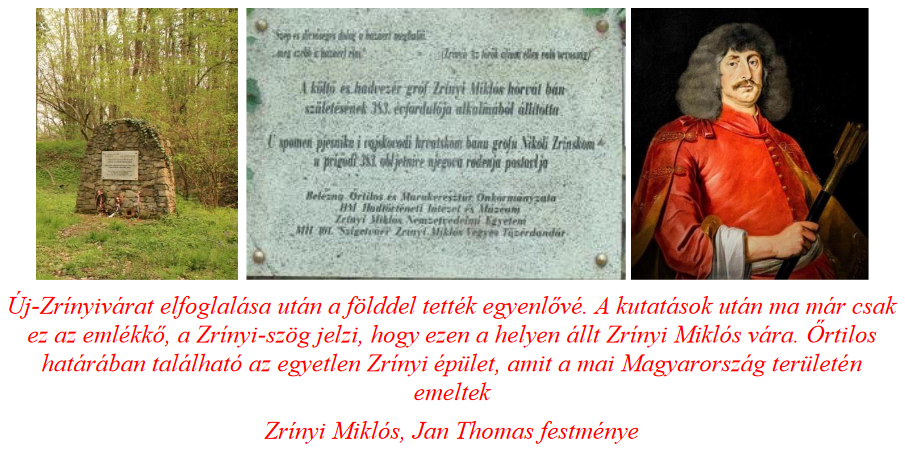

The lord could no longer retreat from here, but he did not want to. His main goal was still the expulsion of the Turks, which he did not give up even when he saw that Vienna did not support him in all cases. As always, the Habsburgs were only concerned with their own interests. The Hungarians were used as decoys and shields. Zrínyi recognized this and stated that only a strong, national army could save Hungary. His fateful step was when he built Új-Zrínyivár in 1661 opposite Kanizsa, about twenty kilometers away on the island surrounded by the Mura and the Dráva. Zrínyi's strategic genius was proved by the fact that the fortress was considered impregnable both in terms of its geographical selection and its castle architecture. It is no coincidence that the court strongly protested against the construction of Zrínyi's castle. However, the excellent strategist also knew that in order to achieve his goal, he had to win over some of the Hungarian lords. To this end, in 1663 he made an alliance with the regional judge Ferenc Nádasdy and Palatine Ferenc Wesselényi.

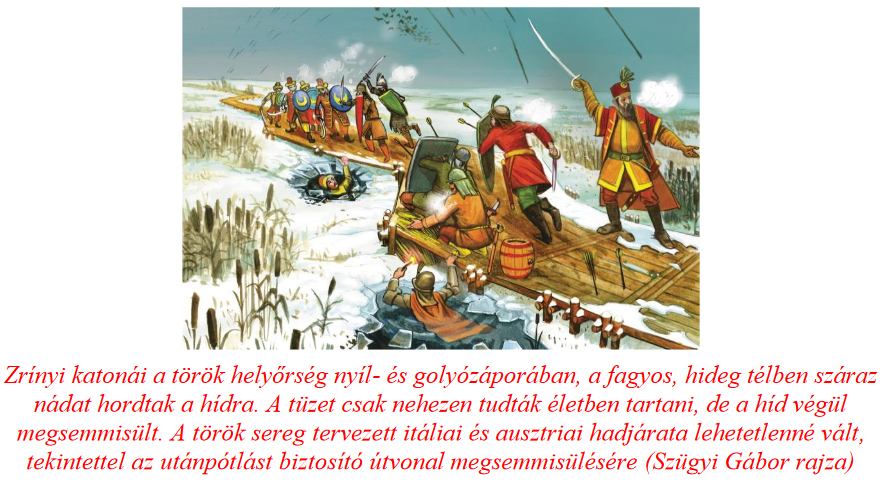

Even the excellent general of the emperors, Montecuccoli, could not stop the Ottoman armies advancing towards Vienna. Emperor Lipót I and the Hungarian king therefore appointed Zrínyi as commander-in-chief of the Hungarian armies. Lipót Habsburg's calculation worked. Zrínyi chose the impossible. In January-February 1664, in the famous winter campaign, he advanced about 250 kilometers deep into the territory controlled by the Turks with an army of twenty thousand men. He burned the six-kilometer-long Eszék oak bridge that served the Turkish supply, crossing the Drava and the swampy areas, thereby preparing the spring campaign.

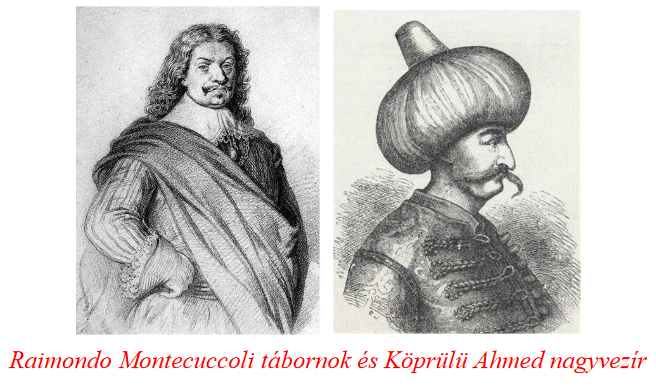

Zrínyi was celebrated throughout Europe after the successful campaign. His valor was recognized with the honorable name "Hungarian Mars". Emperor Lipót wanted to raise him to the rank of duke, but Zrínyi did not accept it. The Pope awarded him with a general's hat, the King of Spain with the Order of the Golden Fleece, and the King of France with the title of feudal lord. The German electors welcomed the 44-year-old general as their father and brother. In Europe, the news that only Zrínyi could defeat the Turks was taken seriously. However, in the spring of 1664, the Habsburgs and their allies, who so often proclaimed their Christianity, spoiled everything. In April, Zrínyi began the siege of Kanizsa, which was protected by the Turks, but Lipó and the War Council ordered him back because the main Ottoman army was approaching Vienna. The united armies, led by Montecuccoli coming from Transylvania, surrendered the parts along the Mura, including Zrínyi's estates. They watched idly as the superior Turkish force occupied and blew up the castle of Zrínyi, built three years earlier. The victorious battle of Szentgotthárd could have forgotten the shameful letdown. However, it was followed by a "peace treaty" amounting to betrayal.

The confrontation between the main armies of the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires was partly contributed to by the Hungarian-Turkish antagonisms in Transylvania and partly in the south.

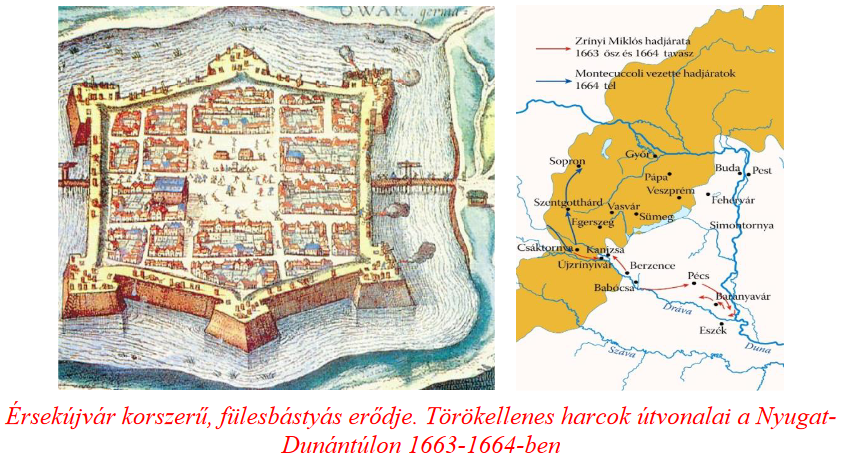

Among others, II. György Rákóczi's failed campaign in Poland in 1657, the fall and looting of Várad, attacked by the Turks in 1660, and the rise to power of János Kemény. Kemény, who occupied the princely throne in 1661, turned against the Turks and sought contact with Vienna. Montecuccoli was already in Transylvania to help János Kemény when Emperor Leopold ordered the Christian army back. The Porta nominated Mihály Apafi to the throne of Transylvania, who won a victory over János Kemény, and was the prince of Transylvania for almost three decades. For Vienna, this meant that everything would remain as it was, it was not worth the risk. When the Turk secured Transylvania, he pushed further west. The sultan was enraged by Új-Zrínyivár, built in 1661, and he wanted to deal with his great opponent, Zrínyi. Köprülü Ahmed, who was appointed grand vizier in 1661, bravely pushed forward, seeing the retreat of the Habsburgs from the Hungarian territories. (For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that most of Lipót's military and political strength and attention was diverted by preparations against the French.) In the fall of 1663, the Grand Vizier captured Érsekújvár, the key to the Highlands, but the castles of Nyitra, Nógrád, Szécsény, and Léva also fell into Turkish hands.

Fate bona, nihil aliud

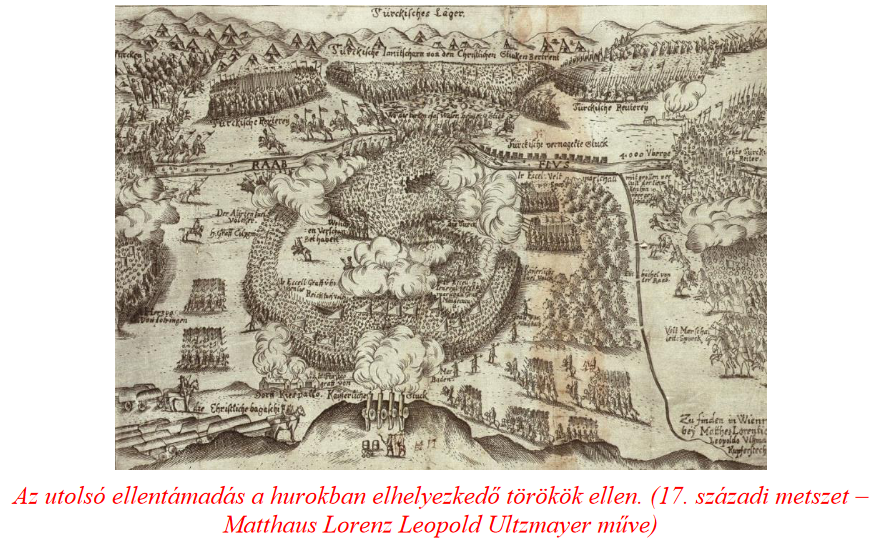

Zrínyi's motto, Good luck, nothing else! true to his bravery in both military and political fields. However, it is not true to the exploitation of his combat successes and his short life that ended tragically. The battle of Szentgotthárd was the outstanding event of the eventful year 1664 throughout Europe. The Christian armies - in the defense of Vienna - clashed with the Ottoman forces near Szentgotthárd. Montecuccoli's army of about 26,000 men clashed with the Ottoman force of 50,000 men. A Rhine force of 10,000 men faced the Turks in the north, and a Rhine force of 25,000 men in the South Transdanubia. Zrínyi commanded a part of this latter army. The Battle of Szentgotthárd began on July 31, 1664. The fight went on all night, and the next day the forces of the two empires continued to fight at the Rába bridge.

European Christian troops led by Montecuccoli won a brilliant victory over the Turks. However, the subsequent peace agreement shocked almost all European rulers, apart from the contracting parties, and filled the Hungarian lords with anger.

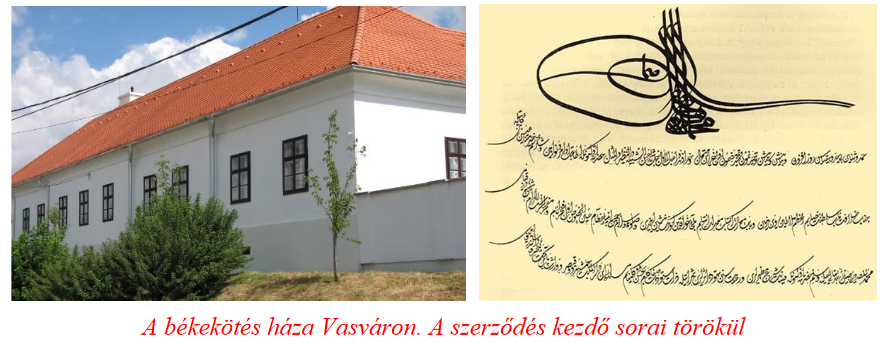

The Peace of Vasvár

The "shameful" Peace of Vasvár, as this event became known in Hungarian historiography, rightly deserved the epithet. After the victorious Battle of Szentgotthárd, the Habsburg-Turkish peace concluded in the fall of 1664 contradicted all military and political reasons and interests. More precisely, the Treaty of Vasvár did not contradict the interests of Vienna and Istanbul, but it disregarded Hungarian interests. Among other things, Lipót supported the Turks in maintaining their authority in Transylvania, that is, he recognized the principality of Mihály Apafi.

They also left Várad, Karánsebe, Lugos, Jenő, Timisoara and a dozen other fortresses in the hands of the Turks. Transylvania left behind one of the bloodiest decades, teetering on the edge of annihilation. However, despite the losses, the statehood of the principality was saved. Apaf was and could still be counted on in European politics. The prince of Transylvania and his court remained a negotiating party in the geographical, military and political fields.

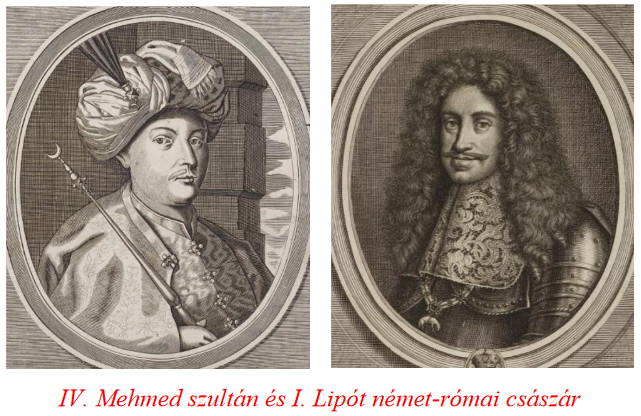

True, the sultan assured Lipót in return for this that he would not give shelter to the enemies of Vienna in the land of Transylvania. However, the prince's policy was more nuanced than those outlined so far. It is true that Apafi was helped to the throne by the Turks, but it should be known that the long-term secret goal of the prince and his entourage was a comprehensive campaign against the Turks. Apafi won XIV for his plan against the Turks. Also the verbal support of King Louis of France /Sun King/. Knowing this, the organization continued in Transylvania and Hungary. However, the Peace of Vasvár ruined everything. It is worth noting that Vienna's sophisticated and cunning politics could not be easily deceived. (The peace was concluded by the envoys of Lipót and Mehmed.) Neither the leaders of the Principality of Transylvania nor the Kingdom of Hungary could participate in the Vasvár negotiations. This also indicates that neither Turkey nor Vienna supported Hungarian interests in the slightest.

However, the greatest shame of the Vasvár peace treaty, which provoked the anger of the Hungarians, was that the victorious Habsburgs left the key of the Highlands, Érsekújvár, in the hands of the Turks. Miklós Bethlen, acting as ambassador between Paris and Gyulafehérvár, had just arrived at Csáktornya, where negotiations against Vienna began with the assembled Hungarian lords. The desperation of Miklós Zrínyi was also increased by the fact that he replaced Lipó as the commander-in-chief of Hungary and replaced him with Montecuccoli, who was more reliable for Vienna. However, the organizing lords could not carry out their ideas. On November 18, 1664, Miklós Zrínyi, who formulated the establishment of an independent Hungarian army and the formation of national policy, suffered a fatal accident in the Kursanec forest near Csáktornya - where he was participating in a hunt with the lords who were guests.

The death of Miklós Zrínyi

The official Hungarian historiography unanimously states that the death of Miklós Zrínyi was caused by a wild boar. Even then, there in the Kursanec forest, doubts arose about the death caused by the wild boar.

The main source of the already mentioned official historiography is Chancellor Miklós Bethlen's Autobiography, in which the accident caused by the boar can be read. However, the researchers do not add that the "only eyewitness", Miklós Bethlen, who was only 22 years old in 1664, wrote down his memories nearly half a century later, at the age of 66. They also do not add that the Transylvanian lord, who ran a brilliant career, wrote his memories of the death of the "Hungarian Mars" in his prison cell in Eszczecin and then in Vienna (1708-1710), under considerable pressure from the Viennese court.

The person of István Póka, the chief hunter, raises even more problems. You can read the text presented as evidence in the CV. The described situation is absurd. The biggest lord of the country is attacked by a wild boar, and the chief hunter climbed a tree in fear. This is as unbelievable as the whole wild boar attack. Even today, a hunter would not let down his fellow hunter in a similar case, not that a chief hunter would let his master down. All of a sudden, where Guzics is hanging out, he says to his brother: The carriage is coming soon, the master is there. We went as soon as the carriage could move and I ran into the thicket on foot, and there he lay, still holding his left hand, as I liked, his pulse beating weakly, but his eyes were not open, nor did he speak, he just died. Majláni spoke like this: that as soon as Poka ran into the forest on the pig's blood, while they were tying up the horses, all they could hear was the sound of woe; It was a spider's word. Majláni was the first to arrive, Poka on a hooked tree, the master with his face on the ground, and a male on his back; he approaches; the pig runs away... True, it was not revealed about the identity of the Croatian hunter, where he came from or who hired him. Even his contemporaries spoke of him as Vienna's secret man. Miklós Bethlen was not there at the scene of the attack, he only saw Zrínyi when he was brought out of the forest.

Contemporaries could not accept the news of his sudden death either, especially not knowing what Zrínyi and his colleagues were up to on the political chessboard.

They talked about a conspiracy, an assassination plot by the Viennese court. However, it is worth knowing that no investigation was carried out against Póka, and in fact, the main hunter disappeared without a trace.

One of the young people of March, Pál Vasvári, was the first to describe in the middle of the 19th century that Miklós Zrínyi was killed by an assassin hired by the Viennese court, and that his death was not an accidental hunting accident. Later, several writers, poets, and researchers dealt with the topic. Among them is Grandpierr K. Endre, who in one of his books listed the evidence based on contemporary documents for about a hundred pages, that Zrínyi was murdered by the court. The facts in this case are also supported by the fact that Zrínyi's death was exceptionally well-timed for Vienna.

It is difficult to decide whether the tragedies of Hungarian history strengthen or weaken the "conspiracy theories".

The official Hungarian historiography - of course there are exceptions - constantly asserts the canon that prominent personalities serving Hungarian interests, if they die at the wrong time and in the wrong place, cannot be linked to any kind of "assassination". Anyone who claims the opposite is a servant of conspiracy theories, is not a professional, and misleads the reader, viewer, and listener. They have only one answer to the tragic events that have happened over the course of a thousand years, which are always disadvantageous for Hungarians, that they are fake news, the products of fantasy and ignorance. The skeptics, on the other hand, claim that they have at least as much historical evidence for the assassinations - what's more, in terms of the logical connections of our history, they can be discussed with more weight - than the well-paid "professionals" who treat our history almost with disgust. There is no place here and there is no need to go into details, only the well-known events are worth mentioning.

We can start with Kursán, who arrived in Bavaria in 904. The nobleman leading the Hungarian delegation was secretly murdered by the Bavarians. Even historians following the official line do not deny this. The Battle of Bratislava in 907 - which some still claim never existed - was a snappy response to the German assimilation attempt. (Almost without exception, the deaths served the interests of the Germans and the Habsburgs, who were our allies. From time to time, Venetian and Florentine poisoners also helped send the struggling Hungarians to their graves.)

We don't know much about Szent Imre's vadkan. One thing is certain, however, that it was very bad for us, because the German-Venetian-educated Péter Orseolo could come to the Hungarian throne. They murdered the first freely elected Hungarian king, Sámuel Aba, and a dozen other rulers of the Árpád family, who died young and before their time. Foreign pallos ended with László Hunyadi, and then in 1490 the poisoned fig with Mátyas Hunyadi. It is fortunate that our last king, who ruled independent Hungary, did part of his work. The death of Mátyás Hunyadi is also subject to controversy.

Even today, we do not know for sure how II, who escaped from the Battle of Mohács, died.

King Louis. It is least likely that the Csele drowned in the stream. The fate of István Bocskai, the Transylvanian prince who defeated the Habsburgs, also raises questions, since he was at the height of his strength when he suddenly fell ill and died in Kassán in December 1606. Péter Zrínyi was executed by the Habsburgs in Bécsújhely, and Miklós Zrínyi was executed by a wild boar named István Póka. II died in exile, in a foreign land. There is no dispute about Ferenc Rákóczi, Imre Thököly, Ilona Zrínyi, Lajos Kossuth, Miklós Horthy, István Bethlen - just to mention the prominent leaders of the Hungarian state. However, Count István Széchenyi's death in Döbling is already a mystery, as is Pál Teleki's tragedy in the Sándor Palace in Buda. It is only because of Hungarian fate that no country in Europe in the 20th century suffered such a tragedy, such a national death, as Hungary at Trianon. Perhaps this is where the Western revenge campaign triggered by the Battle of Bratislava ended? Unfortunately, it is unlikely, because the political, economic, cultural and religious persecution against Hungarians continues even at the beginning of the 21st century.

A history-loving doctor from Szombathely has reconsidered the death of Miklós Zrínyi, and raises more than interesting aspects. Dr. István Nemes is the chief physician of the maxillofacial and oral surgery department at the Markusovszky Hospital, who raises new aspects based on the book published in 1965 by the historian Géza Perjés. When Miklós Bethlen was being transported home from the forest, he discovered human fingernail marks on the dead man's wrist, which indicates that he was captured and killed. Dr. Nemes condemns the "wild boar" historians, who also refer to the testimony of Palatine Pál Eszterházy, who was not even present at the hunt. The deep neck wound on the right side could have been caused by a wild boar, but due to Zrínyi's body position, it is rightly suspected that he was a foreigner. A similar wound can be inflicted with a hunting knife or a brush cutting tool, and it is also likely that he was attacked from behind. Epithelial injuries that seem insignificant have a different meaning in the eyes of an expert doctor than the scribes who believe in a death caused by a wild boar.

Miklós Zrínyi is a poet as well as a writer

According to Zrínyi's own testimony, he considered himself primarily a politician and a general. Despite this, if he had only left behind his literary work, his name would still be known and recorded in Hungarian literary history. Miklós Zrínyi is one of the most prominent figures of 17th century Baroque literature. He also served his country with his pen, which is proven by almost all of his works. The diversity of his writings is indicated by the fact that, in addition to his works with historical and political themes, a number of love poems and military science works were published. His main work is the heroic epic entitled Szigeti vesedelem, consisting of 15 cantos, which he wrote between 1645-1651. The work commemorates his great-grandfather, but also commemorates Hungarians who preserve national morality and defend Christianity. For centuries, it also sends a message to the people of today when it proclaims the historical vocation of the Hungarian nation. The structure of the epic, the four-rhymed, twelve lines, revive the Hungarian historical song. The formation of the creed of the great-grandson is also due to the great-grandfather.

Miklós Zrínyi's poetic ars poetics also refers to the politician and general:

"I do not write with a pen,/ with black ink/

Only with the edge of my saber/ with the blood of the enemy/ My eternal news!

The writer's work on military science was influenced by the style of Péter Pázmány, just like other authors of the time. The Tábori kis tracta (1646-1651) was a contemporary military regulation, and the Valiant Lieutenant (1650-1653) outlined the figure of an ideal military leader. Both works were written with an educational purpose, and the idea of setting up an independent Hungarian army was also formulated in them. Attention was drawn to the values of the Hungarian national past in King Mátyás's work entitled Reflections on Life and A Remedy against Turkish Opium.

Among other things, he earned the wrath of the court with these works when he called for the establishment of an independent Hungarian army. That being said, the Hungarians would be able to drive out the Turks on their own, and we could get rid of the Habsburg oppression. As he said: "For those who want, nothing is difficult!" As if the reformed István Bocskai in 1605 and Gábor Bethlen in 1629 "If God is with us, who is against us?" he would have rhymed the call to Hungarian resistance and independence to the biblical text written on their flags.

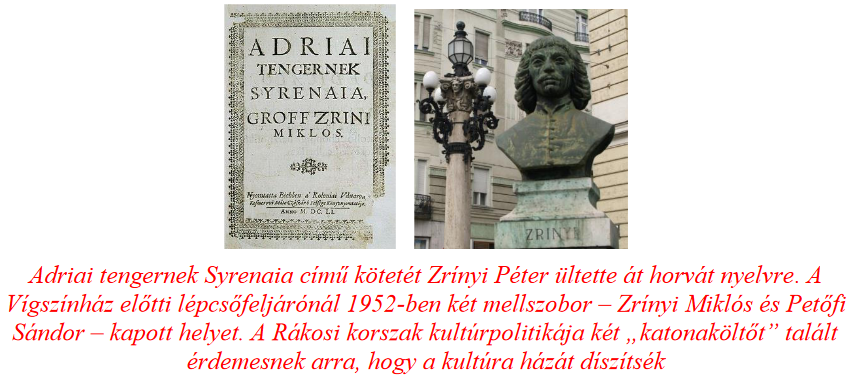

Don't hurt the Hungarians! Poor Hungarian nation, have you gotten so far that no one will cry out your last peril? so that no one's heart will be grieved by your corruption? that no one would say a word of encouragement in your last struggle with death? Shall I alone be your watchman, your watchman, shall I reveal your danger? - say some famous lines of The Turkish Opium Remedy, which reflect the creed of the great poet. Already at the age of twenty, Zrínyi felt the urge to express his emotions in poems, which naturally focus on the young man in love. Such is the volume of the Adriatic Sea..., which captures the free world by the sea, the baroque feeling of life of the siren poet (Zrínyi) in verse.

Among the statues of Hősök tere?

Let's play with the idea! In the area of Heroes, if a statue exchange were to take place, or what would be even fairer, if two new statues were to be added to the Hungarian historical pantheon from St. István to Lajos Kossuth, then the statue of Miklós Zrínyi would definitely have a place there. Referring to his great-grandfather Miklós Zrínyi (VII), who is of Croatian origin, but with an indisputable Hungarian identity, and taking into account the political conditions of his own time, he declared himself Hungarian. Posterity couldn't do anything else either! Zrínyi's whole life was in the fight against the Turks, in the defense of Christianity, and when he had to choose between his country and his loyalty to Vienna, he fought for Hungary, for which he paid with his life.

Author: historian Ferenc Bánhegyi

(Header image: screenshot)

The parts of the series published so far can be read here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28., 29/1.,29/2., 30., 31., 32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46., 47.