"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

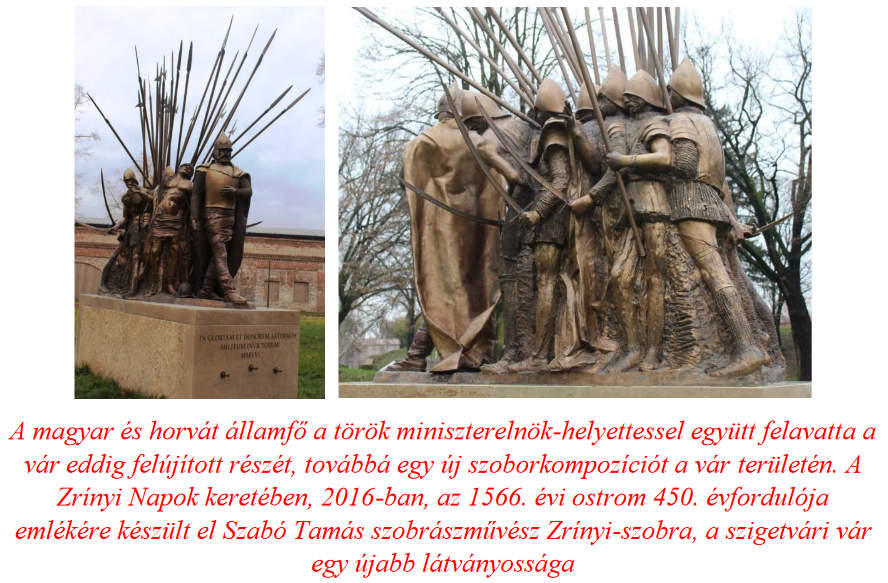

Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated

Zrínyi's fight for Hungarian independence against the great powers

From the moment when the Hungarians returned to the land of their ancestors in the Carpathian Basin 1,100 years ago, they were subjected to continuous attacks. This fight is the 16-17. continued in the century. This is the era when, among others, the people of Zrín saw eye to eye with the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires. Today, we would say that we came face to face with the "global" superpowers.

The 16th century was the lowest point in the history of the Kingdom of Hungary, when the Turks occupied a third of the country. With the division of Hungary into three parts, an era followed that marked the end of the country's independence. This is what the story of the Zrínians is about. But this is also the history of the Transylvanian Principality, Royal Hungary and the Turkish Subjugation. The 17-18. century resulted in a mournful period of the destruction and deliberate destruction of the Hungarian people.

The five centuries following the tragedy of Mohács and the assassination of Szulejmán Nagy in Hungary created fatal conditions in the Carpathian basin. The period from the conquest to the death of Mátyás was spent repelling the attacks of the great powers, but Hungary remained an independent power. After the death of King Matthias, the national independence of our country ceased. The Ottoman Empire was at the peak of its power, and it was then that the Habsburg Empire, which usurped half the world, was built.

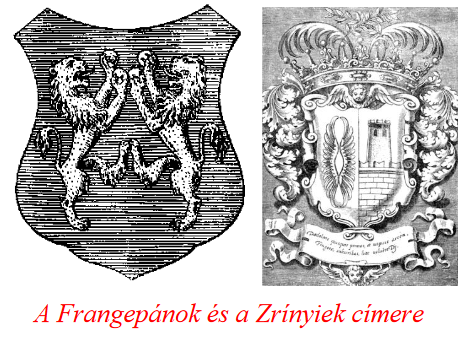

Our history spanning one thousand and one hundred years had defining figures. Among them are the people of Zrín of Croatian origin. The names of four Zrínyis who made this Hungarian-Croatian family famous stand out in the public mind. At the time, Miklós Zrínyi (IV), the first count, was the heroic castle captain of Szigetvár. The second famous personality of the family is count Miklós Zrínyi (VII), the great-grandson of the famous poet, general and politician, the hero of Szigetvár. The third is Count Péter Zrínyi, Miklós's brother. Like his great-grandfather and brother Miklós, Péter Zrínyi died unnaturally. The executioner of Vienna finished him off. The fourth prominent family member is Ilona Zrínyi, daughter of Péter Zrínyi, II. Mother of Ferenc Rákóczi. The heroic defender of Münkac Castle, celebrated throughout Europe, ended his life in exile in Turkey, fleeing the revenge of the Habsburgs.

Accession of Croatia to the Kingdom of Hungary

The concept of accession may be a cause for debate, but the Croatian campaign launched by St. László (1077-1095) in 1091 was not organized with the goal of conquest or an attack on the Croats. It happened that after the death of the Croatian king Dimitar Svinimir (1076-1088), the widowed queen Ilona Árpád-házi, who was the sister of King László, asked the Hungarian king for help. The Croatian nobility, acting against the dowager queen, sought to gain the throne. The Hungarian campaign was successful, László presumably advanced as far as Tengerfehérvár (today Biograd na Moru). In 1097, only Kálmán Könyves (1095-1116) occupied all of Slavonia at that time, which included Dalmatia as well as Croatia. Italian cities, the German-Roman and Byzantine emperors also claimed the coastal ports, and the Pope did not take kindly to Hungarian expansion either. Croatia and Dalmatia became part of the Holy Crown based on the peace treaty, and this association was only ended by the First World War in 1918.

The origin of the Zrínyi family - The age of the Árpáds

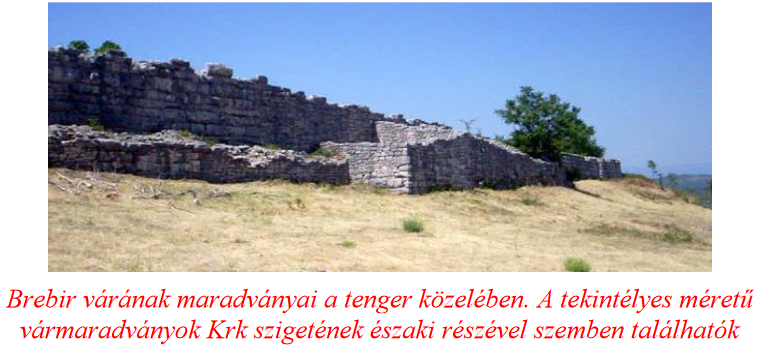

As far as we know, the roots of the Zrínyi family go back to the beginning of the 12th century. The name of the Subics family - the maternal ancestors of the Zrín family - can already be found in a certificate from the time of Kálmán Könyves. The Hungarian ruler took possession of Croatia in 1102 after his predecessor, Szent László, made an alliance. The Subics were one of the twelve Croatian clans that entered into an alliance with the Hungarians. At the end of the 12th century, III. During the campaign against Venice, Béla (1172-1196) gave the Brebir castle in Dalmatia to the Subics in exchange for the support of the Croats. The family took the title of count instead of the humble dignity they had been wearing until now. The counts of Brebir, as they called themselves after their estates, already served the Kingdom of Hungary at this time. Later, when IV. Béla (1235-1270) found safety in the castle of Trau, the king and his family were supported by the Subics. King Béla reciprocated the support by bringing the Croatian tribe to new territories. At the end of the 13th century, the Subics family already received the dignity of ban.

The Age of Sigismund of Anjou and Luxemburg

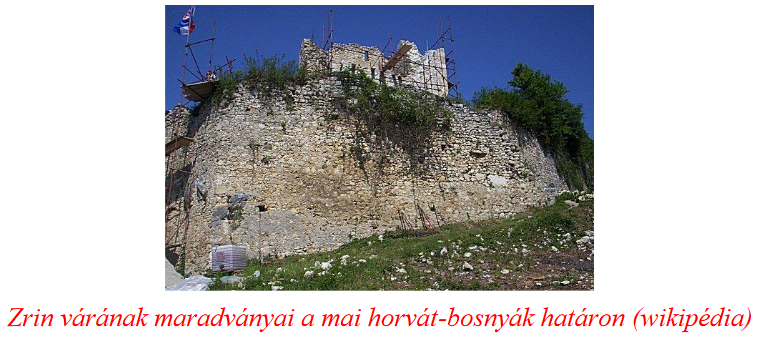

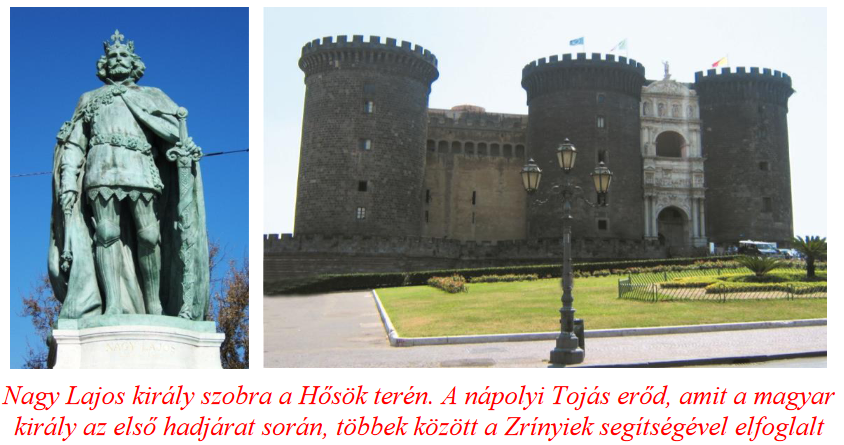

The wars continued under the Anjou kings. In 1347, Lajos Nagy (1342-1382) donated the castles of Zrin and Pedalj to Gergely Subics and György Subics in exchange for the Dalmatian estates by the sea, including Ostrovica castle. The fortress of Zrin /Zryn/, built in the 13th century, became the property of the Babonics. (The castle is located on today's Croatian-Bosnian border.) After that, György and his successors, who aspired to greater power, abandoned the name Subics and exclusively used the Zrinski version, i.e. they took the name Count Zrínyi. The founder of the family can be considered György I. Zrínyi, who grew up on the island of Krk, in the house of his uncle Duimo Blagai. This is how the people of Zrín came into contact with the Blagai and Frangepán clans, who were already related to each other.

In 1347, King Louis the Great of Hungary led a campaign against Naples. The young George joined the King of Anjou and distinguished himself by his valor during the campaign. When György Zrínyi died in 1361, his heir, his only son Pál, was still a minor. The Hungarian king appointed Bertalan Blagai and his son István as guardians. After that, property lawsuits lasting for years began, which were put an end to by Queen Mária (daughter of King Louis) in 1383 after the death of Louis the Great. According to the order issued in Zagreb, all litigation against Pál I. Zrínyi had to be terminated. The properties that had been granted to the Zrínyis up to that point remained entirely owned by Pál Zrínyi. Pál I. Zrínyi thanked this by, among other things, remaining loyal to the Hungarian kings until 1414, the end of his life. (The son of the family founder was buried in a monastery near Zagreb.)

Pál's son, Péter I. Zrínyi, born in 1408 (?), fought against the Hungarian king Sigismund of Luxemburg (1387-1437), on the side of the rebel Croats. Later, however, Péter surrendered to Zsigmond, who accepted him into his service in 1420. Péter I. Zrínyi further increased the glory of the people of Zrínyi and, last but not least, the size of their estates. When the last scion of the Dalmatian branch, Jakab Subics, died - as he had no children - in 1441, all his estates became the property of Péter I. Zrínyi. The will was also confirmed by the governor of Hungary, János Hunyadi.

The age of the Hunyadis

Péter I. Zrínyi had nine children, of whom four were girls (Katalin, Klára, Margit, Ilka) and five were boys (Henrik, Pál, György, Márton, Péter). The family inheritance was inherited by the youngest son, Zrínyi II. Peter took it further. Péter was born in a bad time and not in the most fortunate place, since in the second half of the 15th century, the Turkish conquerors launched new fierce attacks against the southern regions of the country. The Ottoman devastation of Croatia in 1458 was compounded by the war between the lords. János Hunyadi had been dead for two years, László Hunyadi a year. The young Mátyás ascended the throne this year after being released from captivity in Prague. A part of the Croatian aristocracy did not recognize László V, who was under the influence of the Cilleites, as their king. They supported the power of Frigyes Habsburg (1452-1493), who was considered the lesser evil at the time.

In 1475, Ahmed Pasha, the lord of Bosnia, advanced as far as Zrin Castle, but was unable to capture it.

Seeking revenge, compensating for his failure, he destroyed and robbed the whole of Croatia. Ahmed invaded Carinthia and Styria, from where he returned with many thousands of Christian prisoners and enormous booty. On his way to Bosnia, he again tried to capture the castle of Zrin. Zrínyi II. However, Peter clashed with the Turks and almost completely destroyed the Muslim army. After the death of Matthias, in 1493, Jakub Pasha launched a retaliatory campaign from Bosnia, but the Christian army of Frangepán Bernardin triumphed over the conquerors at the Una river. However, the Turks continued to push towards Carinthia. He fought several successful battles along the way. the detour in Carinthia, Jakub Pasha turned back at the head of his army and won a significant victory over the Croats near Udbinia (Korbávmező) in 1493. In the battle, Zrínyi II himself. Péter and his son Zrínyi III. Paul also fell. (Three decades later, Pál's son, Mihály Zrínyi, died on the plains of Mohács.) The self-sacrificing struggle of the Zrínyi people against the Ottoman conquerors was already evident then.

The heroic death of the two Zrínyis (Péter and Pál and Károly Korbáviai) created the tradition of the Zrínyi family's brave stand in the

wars against the Ottomans. The relationship and even the union of the two families took place at the end of the 15th century, when Miklós Zrínyi (III.) married Ilona Korbáviai, the daughter of Count Károly, who fell in 1493. Ilona's brother János Korbáviai became the head of the family and the heir to the huge estates. However, Count János - although his power had already risen above the Frangepans - did not marry and could not have children. In 1509, a treaty was signed between Count János and the Zrínyis, which then led to the rise of the Zrínyi family. In the treaty, it was stipulated that after János's death, the huge estate complex - which included twenty-one castles - would fall into the hands of the Zrínyis. It was born in these years Miklós Zrínyi (III.)'s two sons, Miklós and János.The order of inheritance was recorded in writing.

Miklós Zrínyi's youth

Miklós Zrínyi - the hero of Szigetvár - was said to be 58 years old in 1566, the year of his heroic death, therefore his year of birth must have been 1508. The Croatian name of Miklós Zrínyi (IV.) was Nikola Subics Zrinski. We don't know much about Miklós's childhood, but the everyday life of the Zrínyi family can be inferred from the life of his youth in the Southern Region of the time. The armed struggle against the Turks and politicization were decisive in the life of the young Miklós. The young Miklós Zrínyi also mastered militancy, the science of weaponry, and the technique of politics through his participation in the social life of the time. A successful marriage, i.e. joining a wealthy family, was one of the possibilities of social advancement. However, Miklós raised the Zrínyis, who had already gained fame, power, and wealth, to the highest dignities, which he owed primarily to his outstanding military talent.

The nobles living in the 16th century, who accumulated property and aspired to high positions, were often not selective in their means. Among them was Miklós Zrínyi, who came face-to-face with several fellow nobles, and on many occasions they fought a life-and-death battle against each other. As an example, it should be mentioned when he took up arms against Bálint Török for the acquisition of the castles in Csurgó and Vrana on the coast and their territories, and against Bishop Simon Erdődy of Zagreb for the acquisition of the Slavonian estates. Violence was not uncommon in Miklós Zrínyi's struggling life. However, this provoked the fear of the peasantry of his estate, as well as the dislike of Vienna, which wanted everything for itself. However, given that Count Miklós did not negotiate with the Turks under any pretense - unlike some of his fellow nobles - he exterminated them wherever and whenever he could. Thanks to this, the Habsburgs were lenient towards him.

It is no exaggeration to say that Miklós Zrínyi, who was feared by the Turks, was almost considered the successor of the Turkish beater János Hunyadi. It should be known that after 1526 the Hungarian lords of the time wavered whether to side with János Szapolyai (1526-1540) or Ferdinand Habsburg (1526-1564), which was decided by their short-term and long-term interests. It was not uncommon to switch between serving one king and another. Miklós Zrínyi never wavered, for a single moment, he firmly stood by Ferdinand Habsburg. Let's add that, among other things, the location of his properties also contributed to this. In addition to Bálint Török, crown guard Péter Perényi was also one of Miklós Zrínyi's fiercest enemies. (For example, Bálint Török lost the support of Vienna and with it a significant part of his Transdanubian possessions by siding with King János Szapolyai.)

It is worth comparing the conditions of the 21st century, i.e. today's Europe and Hungary, with the conditions in the Carpathian Basin in the 16th century. The similarity is uncanny, including, of course, the different social conditions. The Kingdom of Hungary, which was divided into three parts, inherently contained three types of interest systems. Consider that during the Turul dynasty there were still uniform legal obligations in force, which all residents of the country accepted. (Note: If, for example, Ferenc Rákóczi had been asked what the Árpád era was, he would not have known. Then and even later, the first four centuries of Hungarian history were known as the Turul dynasty.) Here we quote the thoughts of the literary historian Tibor Klaniczay, who He was a good connoisseur of the Zrínyi era. (Perhaps, his work fell during the decades of the Kádár era.)

“They lived their lives between extremes; their actions and political decisions were full of fluctuations. Among the driving forces of their actions, money, the desire for power, and the desire to accumulate and increase land holdings played a major role. Their political behavior and position fluctuated more than once, either against the Turks or the Germans. They fought with each other, although they were always forced to unite, sometimes against the Turks, sometimes against others. But if the course of their lives put these lords in positions where it was in their interest to hold on, then they stood there stubbornly and heroically, and were ready to shed their blood for every inch of their home, if necessary."

Miklós Zrínyi's military virtues and unwavering perseverance were combined with excellent political sense. The sequence of events that took place in the 1530s in the Southern Region - which, let's add, was considered the region most threatened by the Turks - is typical of its activities. The frequent turnovers even put a part of the aristocracy in danger. However, Zrínyi was also careful not to come into open conflict with the lords above him in rank and power. On the other hand, he attacked the weaker ones mercilessly if his interests so desired. Among other things, it was considered a daring undertaking when, in May 1539, he killed the Slovenian-born Hans Katzianer, who had previously been the royal commander-in-chief, in the castle of Kosztojnica. In 1537 - when he lost the Battle of Essene - Katzianer switched to the side of King János Szapolyai. The general previously celebrated by Vienna was disgraced, but even then he had a significant military force behind him.

Katzianer's assassination is a source of controversy among both contemporaries and historians living today. However, let's take into account that if Katzianer separated Slavonia and Croatia from Royal Hungary, it would have had serious consequences. When Miklós Zrínyi committed the assassination, he did it primarily not because of his loyalty to Vienna. His own interest also wanted this, because if Croatia were to come under Szapolya's possession, then the huge estate on which the Zrínians based their strength and power would have been pulled from under the family's feet. In the eyes of Miklós Zrínyi, Katzianer was not only a traitor, but also a sworn enemy of his homeland, who drove water to the mill of the hated Turks. The elimination of Katzianer led Ferdinand to the decision that in 1541 he transferred the huge estate of Korbávia definitively to the ownership of the Zrínyi brothers. It happened after all this that Miklós's brother, János Zrínyi, lost his life in an unfortunate clash. Thus Miklós Zrínyi became the sole owner of the huge estate.

1542 is a black year in Hungarian history

When the Turks captured Buda on August 29, 1541, the dark era of Hungarian history began.

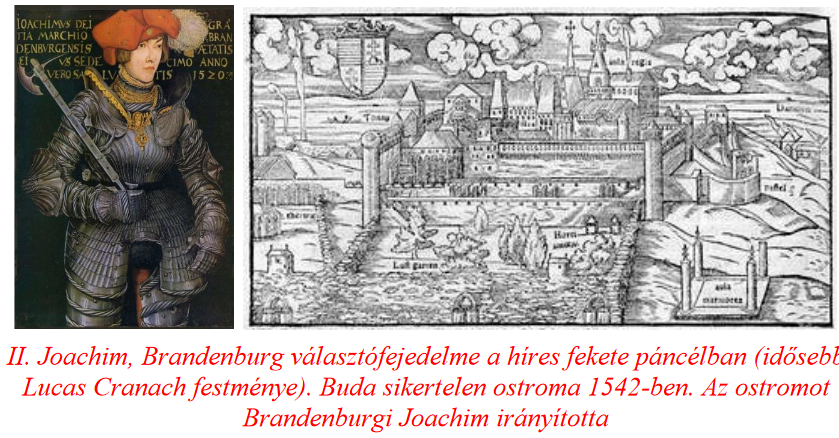

The devastating Mongol invasion, the extinction of the Árpád house , a series of throne disputes, the Dózsa Peasant War, and the Battle of Mohács hindered development. However, it had not yet happened that the foreign power that wanted to invade the country would occupy the capital and tear the country into three parts for a century and a half. Although Elector Joachim of Brandenburg besieged Buda Castle in 1542 by imperial order, the siege was unsuccessful.

It became clear that Ferdinand Habsburg had lost the capital of Hungary and the central, largest agricultural areas of the country. In the meantime, Miklós Zrínyi, at the head of his hussars, fought a victorious battle against the Turkish guard in Pest, which, however, did not bring any significant changes. Nevertheless, this also contributed to the fact that Ferdinand appointed Miklós Zrínyi the ban of Croatia and Slavonia on Christmas 1542. In the 16th century, this was considered one of the most important ensign honors. The royal appointment was not without ulterior motives. After all, Vienna needed a general and a politician who was not only willing, but also able to fight against the Turks.

IN THE MIDDLE OF THE 16TH CENTURY, CHRISTMAS DID NOT YET HAVE THE APPEARANCES AS WE KNOW IT TODAY.

THE PINE TREE CONSTITUTION SPREAD IN HUNGARY - BASED ON THE GERMAN EXAMPLE - ONLY IN THE 18TH CENTURY. THE BIRTH OF JESUS, THE COMING OF THE NEW LIFE WAS ALREADY KNOWN IN THE COUNTRIES OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE, INCLUDING IN OUR COUNTRY. THE 16TH CENTURY BROUGHT SO MUCH CHANGES THAT THE CELEBRATION OF CHRISTMAS MOVED INTO THE HOMES OF FAMILIES. OF COURSE THE CHURCH STILL MEANT THE CHRISTMAS CELEBRATION OF EACH COMMUNITY.

The Croatian ban of Miklós Zrínyi was increasingly burdened. This was the period when Sultan Sülejmán Nagy launched a comprehensive attack on Hungary. In a few years, around ten castles and their belongings fell into Turkish hands. The loss of the castles was also worrisome because the ban's sources of income dwindled more and more. And Zrínyi desperately needed the money from his own estates, since the Vienna and papal promises regarding defense costs remained only promises. If help did come, it usually came late and incompletely. In 1542, the ruler appointed Zrínyi as the governor of Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavs.

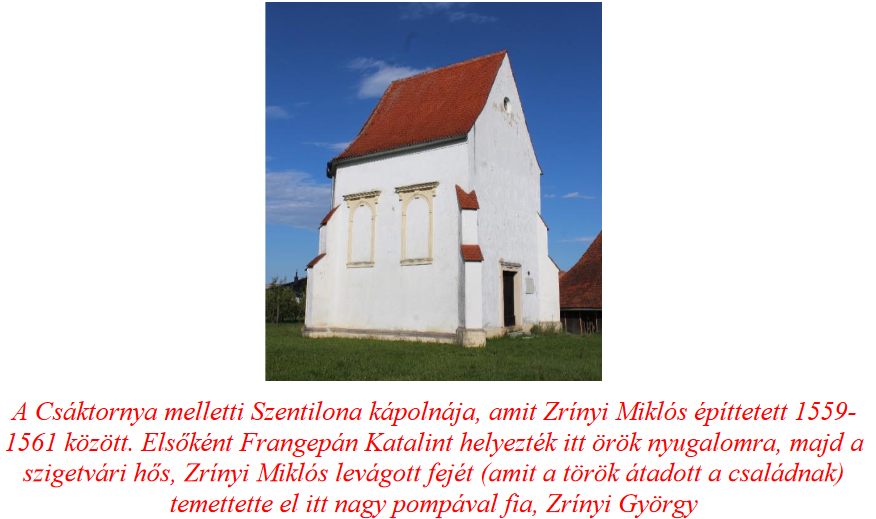

In the summer of 1543, a decisive turning point occurred in the life of Miklós Zrínyi, when he married

Katalin Frangepán, from the Ozal branch of the Frangepans, the daughter of the largest landowner family in Croatia. (Not to be confused with his great-grandson Péter Zrínyi's wife of the same name, Ilona Zrínyi's mother.) The marriage resulted in several estates becoming the property of Miklós Zrínyi. Katalin Frangepán gave birth to seven children, three boys and four girls. In the following years, Miklós Zrínyi increased his estate with several inheritances, among them Csáktornya, located north of the Drava.

Stridóvár, which lies northwest of Csáktornya, should be mentioned among the property acquisitions.

The fortress, built on Roman foundations, was first mentioned in documents in the 13th century.

The castle of Stridó already played a role during the reign of the Anjous and the Hunyadis. King Matthias donated the castle to the banker, János Ernuszt. After the extinction of the Ernuszt family in 1546, it was owned by Miklós Stridóvár and Muravid Zrínyi. The donor in this case is also King Ferdinand, who took the Turkish beater from the southern region into his complete confidence. The fate of the southern castles was sealed by the repeated Turkish attacks. The soldiers of Allah razed the occupied Hungarian castles and settlements to the ground. Hundreds of thousands of the Hungarian population perished or ended up on the slave market in the 16th and 17th centuries. during the century. (You can read more about this in previous chapters.)

Miklós Zrínyi Szigetvári is an outstanding member of the family.

Although he was uneducated, he knew himself in the political games of the time. (Consider the example of János Hunyadi.) As a Croatian ban, he acquired Muraköz and Csáktornya, where he created a new family residence. He carefully planned his positions and possessions in advance and then methodically increased them. However, for a resounding success and to stop the Turks, even more property and money were needed. After all, from the middle of the 16th century - think of the comprehensive Turkish campaign of 1552 - the enemy continuously attacked the country. During these years, Miklós Zrínyi created the Hungarian-Croatian-Austrian military alliance, which served to keep several castles in Hungarian hands. For example, in 1556 - ten years before the fatal siege - Szigetvár was still protected from the attack of the Pasha of Buda. At the same time, however, his relationship with the Croatian lords loosened, which led, among other things, to Zrínyi resigning from the dignity of Ban, which he had exercised for fourteen years. Despite this, in the eyes of the Croats, he has the eternal merit of organizing the border defense against the Turks. Miklós Zrínyi moved with his family to Mogyorókerek.

His military, political, and economic genius is indicated by the fact that in the same year, in 1557, he became master of the storehouse, and four years later, in the fall of 1561, he became the chief captain of Szigetvár. After the acquisition of the southern ends, and in 1563 in Vienna, he was appointed the chief captain of the Transdanubian district. By obtaining the rank of captain-in-chief, Zrínyi achieved that he had influence over the king and the Hungarian orders at the same time. It should be noted that the acquisition of wealth and power by Miklós Zrínyi (IV) was not for his own purposes, as he served the country, the Hungarian nation, and the fight against the Turks.

Zrínyi was one of the first to recognize the potential of self-representation and commissioned his own portrait. He also bought a house in Vienna and sent his son, György Zrínyi, to the court of the Habsburg archdukes to study in the most prestigious imperial circles. He was similarly careful in marrying off his children. He married his daughters to prominent members of the Hungarian aristocracy. This is how the Zrín family became related to the Országh, Thurzó and Batthyány families. However, his son György had already married into the Czech and Austrian nobility when he married Countess Anna von Arcoval.

After Katalin Frangepán's death in 1561, Miklós remarried.

was Eva Rosenberg, born into one of the most distinguished Czech Catholic families By the time of Katalin Frangepán's death, Miklós Zrínyi had already worked his way up to one of the richest landowners in the Kingdom of Hungary, and through his positions he was a member of the highest political circles. In 1563, his name even came up among the persons suitable for the office of Palatine. At the funeral of Ferdinand Habsburg, in 1564, he was able to carry the copy of the Holy Crown at the head of the funeral procession. (With Miklós Zrínyi's heroic death two years later, he gained such glory for the family that he also helped the careers of his descendants.)

When the Zrínyi family moved to Muraköz, bordered by the Mura and Dráva rivers and historical Hungary, they set up a farm in one of the most endangered areas of the subjugation period.

The center of the flood plain-like area became Csáktornya, where the military, economic and cultural activity base of the region was established. By preferring Zala county estates to Croatians, he became a member of Hungarian aristocratic circles, i.e. he openly accepted his Hungarian identity. The attachment of the Zrínians to Vienna was also manifested in matters of faith. After all, when the vast majority of the country's population converted to the Reformed faith, the people of Zrín firmly stood by the Roman Catholic Church. (True, the reformation spread more in Transylvania and the eastern regions of the country.) However, for the sake of completeness, it should be noted that Miklós Zrínyi (IV)'s son, György, supported the reformers as well.

Captain of Szigetvár

Miklós Zrínyi is mostly mentioned in Hungarian historiography only after his heroic death in 1566, as the self-sacrificing captain of Szigetvár, who gave his life in the heroic struggle against the Turks. However, Miklós Zrínyi cannot be mentioned on the same level as the castle captains who gained historical fame in the middle of the 16th century. István Dobó, who defended Eger, István Losonczy from Temesvár, László Kerecsényi from Gyula, György Varkocs from Fehérvár, György Szondi from Drégely were not comparable to Miklós Zrínyi in the economic and power hierarchy. When Zrínyi applied for the post of captain of Szigetvár, his contemporaries were surprised, they did not understand the lord's will. Why did such a great lord, who was also one of the most prestigious among the nobles, want to control a castle? They didn't understand because the cost of the castle on the island amounted to 75,000 forints per year, which had to be paid for despite the income of the estates belonging to it. The castle captain had to reach into his own pocket, and that was the only way he could pay the wages of his 1,800 soldiers. Originally, Vienna was supposed to pay the remuneration of the castle guards, but this was only partially done in the case of many other castles. Zrínyi really took the noble task of defending the country to heart. (A strong similarity can be discovered between him and János Hunyadi. By protecting the Muraköz region and the south-western region of the country, he did a good service not only to the Kingdom of Hungary, but also to the Habsburg Empire and the whole of Western Europe. In addition to his own interests, his moral commitment and his human attitude started it, and thereby set an example to others that the nobility's duty is to protect the homeland even at the cost of their lives.)

The battle of Szigetvár, the final hour of Sülejmán Nagy

As early as 1562, Miklós Zrínyi began to face another major series of attacks by the Turks.

The concerted operation of the Sultan in 1552 shocked the Hungarian aristocrat to the fact that the Ottoman Empire could only be stopped by cooperation at the European level. This decade resulted in the climax of Sülejmán Nagy's European expansion. Although the conquerors suffered an ugly failure at the Battle of Eger, the attacks continued. The captain of Szigetvár knew that the Turks had to be confronted at the southern ends and in Slavonia. Here he could still count on the support of the Croats and other southern peoples, and he also knew that the farther the battles were from Buda and the territory of the Subjugation, the more difficult it would be for the Turks. In the vicinity of Pécs, Zrínyi's hussars were victorious in numerous raids, and along the Dráva they captured and destroyed several smaller Turkish fortresses. The Beys constantly complained in Vienna that Zrínyi was breaking the peace, and Istanbul was flooded with their reports against the island captain. it was clear that Zrínyi opened a new phase of defense against the Turks. If it was up to him, the nation could have recovered from its dazed state after Mohács.

Miksa Habsburg (1564-1576) was not happy with the successes of the Hungarians, because he did not want a comprehensive war against Sülejmán Nagy, he was not prepared for that.

However, Zrínyi refused to give up his successful campaigns, because he rightly felt that he was protecting not only his own estates, his own people, Hungary, but the entire empire. Zrínyi was not deterred even by Emperor Miksa's anger, he sought to acquire additional resources. In addition to undertaking the battles, the castle captain resorted to the ancient Hungarian tactic, the scorched earth method. It is true that it caused considerable damage to the Turks, but it also made the Hungarian population still living in these areas homeless. The flood of complaints arriving in Vienna led to an imperial investigation, as a result of which Zrínyi resigned from his position as castle captain in 1565. However, Miksa did not accept the resignation, because he knew very well that this would facilitate the advance of the Turks. So Zrínyi stayed, but the Porta nevertheless decided to launch a comprehensive attack on the southern ends of Hungary. The Sultan personally wanted to end his four decades of genocide and territorial occupation against Hungary, when he set off against Vienna at the head of his armies. However, in order to achieve the final goal, he had to capture the fortress of Szigetvár, because bypassing it would have put the supply of the Turkish army in jeopardy.

The political events of the time of the Turkish campaign that started in 1566 cannot be ignored. When Miklós Zrínyi, loyal to the Habsburgs, fought his heroic battle against the Turks, Emperor Miksa stood up for Hungarian and Croatian interests only out of necessity, for the sake of appearances. Miksa, who replaced Ferdinand, who died in 1564, had a different personality than his predecessor in many respects, and also chose a different path in his politics. (Miksa was inclined towards the Lutheran faith, which was unacceptable in the Viennese court. To divert him from this faith, he was sent to Spain in the 1550s, where, however, his affection for Luther's doctrines only increased. Finally, he was married to his niece, the daughter of Emperor Charles V, Mária . He had to make a choice. As a result, in 1560, Miksa gave in and made a confession of faith in favor of Catholicism.)

Sülejmán knew well that the divided Hungary was occupied with its own internal conflict, so he boldly advanced towards Szigetvár. However, it should be known that Suleiman also had internal opposition. Both the contradictions within the Porte, the rebellion of the Janissaries, and the failure suffered in Malta the previous year could be best calmed down and remedied with a campaign. The agg Sülejmán also knew that this campaign was the last opportunity of his life's work, during which he could win a victory over the Habsburgs.

The Turkish army of around 50,000 people arrived under the walls of Szigetvár on August 5, 1566, which was protected by only 2,500 soldiers under the leadership of Miklós Zrínyi. The fierce sieges brought results, on August 21, the Turks captured the Old Town. Nearly a thousand Hungarian and Croatian warriors fell during the siege. The work of the defenders was made difficult by the scorching summer heat. There was little water in the castle, and it was tiring to prepare for constant defense against the attacks that did not want to stop. The hopeful news spread that the Christian army camped at Győr would soon arrive and relieve Sziget Castle. They could have known that this would not happen, because the purpose of the international wars and the military leadership was solely to defend Vienna. The overwhelming force, the determination of the Turkish leadership, and the suffocating summer heat wore down the strength and endurance of the defenders. The fate was also contributed by the misfortune that part of the gunpowder stored in the castle exploded, causing great destruction in the ranks of the defenders.

Even if Zrínyi made a mistake during the organization of the defense of the castle, this was not the cause of the fatal defeat. Posterity, which has always respected the heroism of the castle defenders and the captain, also knows that the Sultan died in the early hours of September 7, 1566. The death of Sülejmán Nagy, who led Hungary to the brink of the grave, under the walls of Szigetvár suggests that this news led to the dispersal of the besieging army, and that the castle could have been saved at the last moment. However, the death of the sultan sealed the fate of the castle defenders. The leader of the Ottoman forces, Szokollu Mehmed, strictly concealed the death of the sultan and ordered an even stronger siege in the given situation. He had to capture the castle, otherwise the confrontation with Zrínyi could have ended in an ugly failure.

The Turkish leadership feared that the triumphal march of the sultan, who captured Nándorfehérvár in 1521, won on the field of Mohács in 1526, and annexed Buda in 1541, would fail under the walls of Szigetvár. At the bedside of the dying Sülejmán, the Turkish leaders rightly feared that Hungary would be the fate of the great conqueror. Although it would have just now come true, the great dream that Sülejmán will be the fate of Hungary.

Zrínyi could have chosen between life and death, but the heroic captain chose death rather than surrender. He couldn't do anything else, since then his whole life would have contradicted all his previous actions. Miklós Zrínyi, the Turkish beater from the southern region, the sworn enemy of the Ottoman wars, would not have been left alive if he had fallen into their hands alive. Fate made it so that perhaps the most important sultan of the Turks - as mentioned earlier - met his fate just under the walls of Szigetvár.

The castle fell, the castle defenders were all destroyed, but the Ottoman campaign stalled at Szigetvár. The time wasted on the siege and the strong reduction in the fighting strength and numbers of the Turkish army meant that the western half of Europe could breathe again. As happened a hundred and ten years earlier at the walls of Nándorfehérvár and in many cases after that.

What is the historical significance of Miklós Zrínyi (IV.)? Even in the general memory of Hungarians, we think of his great-granddaughter's nation-building activities and the person of Ilona Zrínyi, who defended Munkács. But without the great-grandfather's economic, political, and military activities, his descendants - however talented and determined they were - would not have been able to achieve the historical fame they did. Because the defense system that was built in the Hungarian-Croatian and Croatian-Slavonic territories over a century and a half was due to the nobility of the Balkans and the southern ends, but above all to Miklós Zrínyi.

Caught between two world empires, as we would say today, two "global powers", the Hungarian-Croatian Kingdom passed the exam well. He primarily defended the Habsburg Empire and the city-states of northern Italy. Let's add that the role of other Christian peoples in the region was not so clear. The Romanians (the people of Moldavia and Havasalföld) stayed out of the bloody battles wherever possible. Even then, their main concern was how to serve the Turks or Vienna in order to gain Transylvania. And the Ráks (Serbs) did nothing but join the Turkish army and exterminate the Hungarians wherever possible. This was already a very conscious and planned strategy on the part of the grids. (It should be mentioned that one of the four official languages of the Ottoman Empire was Rác. One of the richest and most densely populated regions of the Kingdom of Hungary, Bácssórgy and Szerémség, became almost uninhabited. It is telling that the Hungarians disappeared from this region. It cannot be to keep quiet that Sülejmán Nagy's mother was of Rác origin, as a result Sülejmán's native language was Rác.)

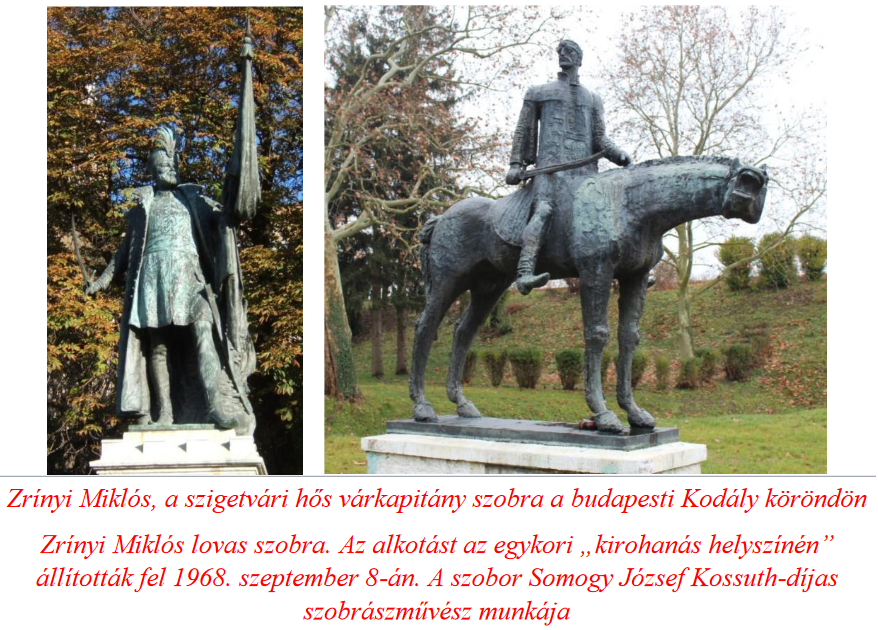

The memory of Miklós Zrínyi (IV.).

The death of Miklós Zrínyi, the Turkish beater from the southern region, would have marked the peak of Szulejmán Nagy's career. What the greatest conqueror of the Ottoman Empire did not think about in the weeks leading up to the war was that he would die a few days earlier than his great rival. He died in the 46th year of Suleiman the Great's reign, a few days before the capture of Szigetvár. It was the end of a "life's work" during which the Hungary of the Árpáds, the Anjous, and the Hunyadis was ruined. From the destruction of the country by Suleiman, a straight road led to Trianon. (This is the subject of debate among historians, like so many other Hungarian historical events. However, no one can dispute the fact that the systematic destruction carried out by the Ottomans over a century and a half demonstrably redrawn the ethnic map of the Kingdom of Hungary.)

Every time Miklós Zrínyi Szigetvárott is remembered, and we have seen many signs of this in recent years and decades, it is inevitable that the historical figure and memory of Sülejmán should not be included. A fine example of this is the Hungarian-Turkish Friendship Memorial Park established in Szigetvár. The area is Turkish property, as the Hungarian city government leased it to the Turkish state for 99 years for only HUF 1. "It is a noble gesture for the destruction that the Ottoman Empire carried out in Hungary for a century and a half."

The work is the work of the Turkish sculptor Metin Jurdanur. Later, a head statue of Miklós Zrínyi of similar size was placed next to the statue of the sultan, which, however, had some humiliating "beauty flaws". Among other things, while Sülejmán's head is made of durable bronze, Miklós Zrínyi's is made of less durable plastic. When the plastic was stretched in many places from the bronze paint, the head shape of the heroic Szigetvár captain was also replaced with bronze.

There is no other country in Europe that would erect a monument to the person who destroyed their country. The strong, independent Kingdom of Hungary for six centuries was destroyed in the 16th and 17th centuries. the successor state of the crumbling Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, and Turkey is the owner of such a monument in Szigetvár, which is a sad memory for us.

In Szigetvár, a positive-sounding monument was erected to the historical person who in 1521 occupied Nándorfehérvár, which János Hunyadi successfully defended in 1456. Five years later, Sülejmán Nagy won a decisive victory over the Hungarian royal army at Mohács. More than twenty thousand Christian soldiers fell on the field of Mohács. But this was not the real tragedy of Mohács, but the fact that Mohács led the country to split into two and then three parts. Every Hungarian has some knowledge of the Mohács tragedy that took place on August 29, 1526. We know that this event is one of the greatest tragedies in Hungarian history, the beginning of the Turkish occupation of the country for a century and a half. (The 500th commemorations to be held in 2026 will enrich the great turning point in Hungarian history with many new archaeological and historical elements.)

The fighters of the Islamic faith destroyed everything and everyone in the country. During the century and a half of Turkish rule, the most mournful era of this merciless extermination is linked to the four decades of Sulejmán's rule. Tens of thousands were killed and hundreds of thousands were taken prisoner or sold as slaves. The ruler, who deeply despised Hungarians and Christians, took great pleasure in murdering men, women, and children. The Ottomans' methods included instilling fear, regular robbery, and the constant harassment of "gyaur dogs". The once magnificent buildings, castles, villages, churches, town houses have been razed to the ground. The population of Hungary was turned into beggars, and our history reached its lowest point in these years. It is not possible to further muddy the past of our nation and mislead the future generation again for the sake of the growth of tourism and some economic advantage.

Author: historian Ferenc Bánhegyi

Author: historian Ferenc Bánhegyi

(Caption image: YouTube screenshot)

The parts of the series published so far can be read again here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28., 29/1.,29/2., 30., 31., 32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46.