One hundred and fifteen years ago, on May 14, 1908, the writer, journalist, and historian György Gracza died, whose most influential work is the five-volume work entitled The History of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–49

Details from György Gracza's writing:

And the whole Olách people are moving. They flock to the designated camp sites in large numbers. The languid light of the October sun breaks on thousands of flashing spears. Even this gathering is a real blow to the defenseless Hungarians of Transylvania. Like the march of locusts, so is the march of this army of marauders. Ahead is terror, followed by destruction. But that's just the beginning. As soon as he reaches his camp, he becomes aware of his enormous power: he is not satisfied with mere plunder, but now begins to thirst for blood.

"God is sleeping, you can do anything," he kept ringing in his ears, like the preaching of his sweet bagpipe priest.

The spiritual dimension, this heavenly spark that raises man to God, is completely extinguished from his heart; and under the control of his wild instincts, he quickly descends into a bloodthirsty animal.

The killing spree starts from Balázsfalva, this flash point of the partisan strike, where ten to fifteen thousand people crowded together.

The unbridled crowd, as soon as the camp starts, covers the entire countryside like a muddy river. Here he searches for weapons, there he robs food. And during this fight, the scattered gangs organize real manhunts against the uri class. No mercy, no selection. Everyone is the object of persecution: be it a weak woman or a strong man, the broken elder is just the same as the gaping child; everyone if they speak Hungarian.

[...] The road to Gyula-Fehérvár winds through a narrow valley between steep mountains. The people of Zalathna flee on this road. The weak legs of the children are broken by the sharp gravel, the exhaustion takes hold on the older ones; but they just keep running, driven by the power of the life instinct.

They almost think they got away with luck. However, at the border of the village of Feness, a group of Močs, which started on their bloody trail, catches up and surrounds them.

It's all over... The caravan of refugees stops: silent, desperate, like those destined for death. Only the silent sobs of women can be heard.

[...] What followed: it cannot be described by pen. A terrible, terrible massacre; an eternal shame in the history of the Romanian people in Transylvania.

The entire band of robbers, in a frenzy of rage, throws themselves at the defenseless prisoners and kills them almost one by one. Blood falls in streams. The heart-wrenching wail of the victims, like a terrible accusation, sobs into the soundless night, and perhaps even the wild animals tremble.

By the time it dawns: the camp site is now eerily quiet. The rising sun casts its weak light on the bloody corpses of six hundred and forty slaughtered Hungarians.

Miraculously, perhaps a hundred and twenty of the entire team escaped. One of them: János Szabó ref. A priest, as a direct eyewitness, remembers the horrific bloodbath in the magazine "Honvéd":

"... Here in Proszák, the Hungarians are laid out on the wet square in the evening; yes, they laid him down, because no one was allowed to stand up, and whoever did so was immediately shot in the head. The weapons taken are distributed among the cores. Now the looting and robbery started. Everyone was stripped of everything. The women's hair was parted: were there no treasures hidden there, women's private parts were violated. First of all, they took away the women's slippers and the men's boots. Throughout the night, they scolded them like dogs and threatened to exterminate the Hungarians.

In the morning, at dawn on October 24, the poor looted Hungarians are ordered to get up. And at the word "go", all weapons are fired at them. And happy was the one who was hit by a bullet, because the rest were beaten to death with spears in the biggest and fiercest battlements.

They spared neither old nor young; no children, no pacifiers. Even the Olachian women took part in the carnage and beat our women to death with hoes.

Zsigmond Császár, a good-hearted lady, was first broken in the head, pierced through the breast with a spear, so that the blood flowed like a stream from both the front and the back, then a spear handle was thrust into her womb, and she was stripped of her armor, leaving only a shirt on her. Perhaps on the third day, when the poor woman came to her senses from her stupor, she wandered into Fejérvár, barefoot and in a shirt, and the castle commander, more cruel than the Oláhs, did not even let her into the castle, she ended up in the hospital in the city, and died after a few days among the terrible people. The 80-year-old old lady Pecherné, Frendl, and Dianics were all elderly people who could hardly move, and they were killed by spears. Three suckling children had their necks slit in front of their mother. Guard captain László Farkas first had one leg, then the other, cut off, then one hand, then the other, and finally he was hit in the head..."

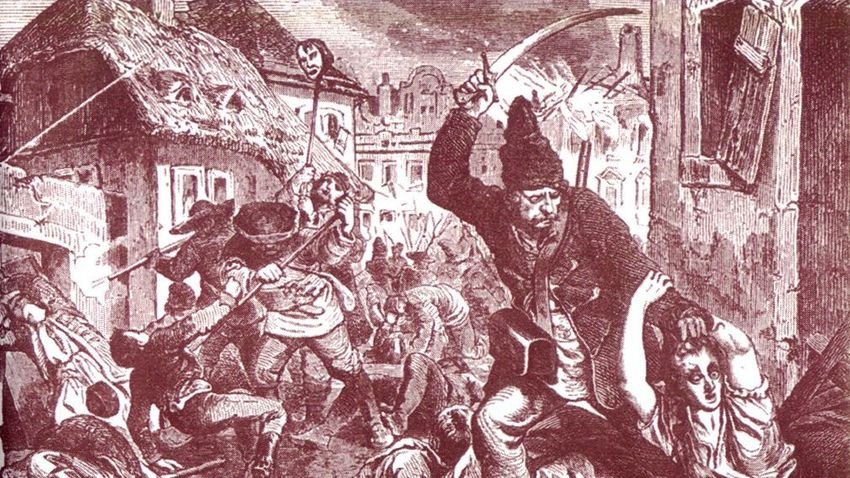

The massacre in Zalatna in October 1848 (Source: Wikipedia)

Zalathna was completely consumed by the fire. All three of its churches, almost all public buildings, and more than a hundred houses were burnt to ashes. But all the mines were also destroyed, these great colonies of work and diligence. And while the disaster raged in the city, the Oláhs began to rob. Thirteen thousand pieces of gold and twenty thousand pieces of silver were taken from the treasury alone. Well, even the private property that has been destroyed! Its value is hundreds of thousands. They searched every house, every apartment. They rolled the wine barrels out into the street from the broken-up cellars, and there they danced among the smoking ruins, accompanied by obscene songs and the shrill sound of bagpipes. Two nights, two days, all of October. This hellish ordeal lasted until the 25th. Then they began to divide the booty; however, over the prey, as usual, they got into trouble and started killing each other. Janku's personal intervention was necessary to somewhat restore order among the drunken mob.

The news of the carnage in Zalathna caused deep consternation throughout Transylvania. Puchner himself criticized the matter and told the revolutionary committee to stop the aimless cruelty. But they did not listen to the admonitions of the commander-in-chief.