Globalism is not only a dead end, but one of the biggest threats to our current world.

During communism, in the shadow of Soviet tanks, we looked longingly to the West. We envied not only democracy, but also capitalism. In fact, mainly that. The well-being, the abundance of goods, the selection, the cool stuff. The world where people can freely do business, found and build companies, and get rich. Was it still an illusion? Or has something changed today?

The question is valid: what is capitalism actually? Where does it come from, how was it created? A library's worth of literature was born on the answers. Obviously, I would expand the scope of this article, but we should look at some basics in order to better understand where we are today, and to find the answer to the question in the title...

There are basically two approaches to the characterization and historical description of capitalism. One, the liberal school, is primarily characterized by psychological and social reasons. (It is very important that we are not talking about today's political-ideological liberals, who are derided as "libertarians", but about classical economic liberalism, which is basically a right-wing idea.)

capitalism is the enforcement of the natural, millennia-old, useful and proven behavioral patterns of man in the world of farming. In other words, people are fundamentally entrepreneurial and experimental, and instinctively strive for efficiency, thereby increasing their own (and their family's, environment's) well-being.

("Prosperity" here means not only material things, but also "well-being", i.e. health, success, happiness, satisfaction, etc.) These natural human motivations then became institutionalized: not only did individuals try to be more efficient and successful, but they also joined interest communities (guilds, "companies", etc.), and created all kinds of binding relationships (contracts, hierarchical orders, etc.) among themselves. And the organization of the states has increasingly developed in the direction of formally creating and maintaining an environment where the mentioned motivations can prevail as much as possible.

The other, the Marxist approach, is actually historical-critical. According to this, capitalism is a specific method of production that was created with the fall of feudalism and the industrial revolution, and is based on the dichotomy of capitalists, proletarians, the wealthy and the have-nots. This approach rejects the idea that it is based on human nature and actually evolved over millennia. Instead, he considers it a new and artificial formation forced on the majority of society.

If we want to philosophize a little about this, then the truth is somewhere in between (but not in the middle): man really has an entrepreneurial-competitive nature, he really wants to be more successful, more efficient (and better than others), for this he is willing to take risks (some to a lesser extent, some to a greater extent) and has been behaving accordingly for thousands of years. But in order for an institutionalized system – or production model – to actually emerge from this, the industrial revolution and the original capital accumulation that occurred parallel to it were really necessary. Classical liberals and Marxists therefore have approx. He is 70-30 percent right in his description of capitalism...

Is capitalism good or bad? The question is wrong from the start, and so are all answers based on emotional and ideological grounds. Capitalism can best be described in one word: it works. If people have the opportunity to do business, to grow, to compete, because they can enjoy the results, then they will take advantage of the opportunities. And they will have more and more motivations, they will become more and more efficient.

And their results and successes are not purely self-serving: successful economic activities create products and services that are useful for others, often valuable innovations for the community as well. (Just to mention one example, for example the Internet.) In addition, they provide job opportunities and a living for other, less successful/talented/hardworking/lucky people.

And a person who is successful in his economic activities after a while can no longer spend all his money on himself, and he finances useful things beyond himself not only from his corporate but also from his personal wealth. Of course, not all wealthy people feel the same way about social responsibility. And individual capitalists and entrepreneurs value their employees and subordinates to different degrees. But man also by nature has motivations and needs that go beyond himself (just think of the higher levels of Maslow's pyramid known from psychology); the statement "capitalism works" means not only that the individual prospers, but also that the system, by its very nature, raises social well-being by itself.

If we look at the reality of the past decades, we see exactly this: capitalism lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. Among them, those who were reduced to poverty by some form of socialism.

Here again, it is important to clarify a few things. Socially useful, functioning capitalism that creates widespread prosperity is not the same as "wild capitalism" without rules and limits. Many social elements must be incorporated, which must be guaranteed at the state level. But when talking about "welfare system", "social market economy", etc. we're talking about (and let's say we use the Scandinavian countries as an example), it actually has nothing to do with socialism. Sweden, for example, is one of the most capitalist countries in the world in terms of business freedom, market liberalization, and the economic environment. The state then collects high taxes from successful economic activity, and from this it has built a social safety net from which a wide range of people benefit. But capitalism is the engine of all prosperity (in Norway, for a couple of decades plus, even oil); without it, not only would there be no social market economy, but the Scandinavians would be fishermen teetering on the brink of starvation (as they have been for centuries).

Compared to all of this, it seems strange at first how much criticism is directed at capitalism these days - even from the right! In fact, primarily from the right.

The political left has become the beneficiary of capitalism, which it once despised, to such an extent that (redefining itself as a "neoliberal") it operates its institutions, and in order to maintain its own positions, it is precisely it that most dogmatically rejects criticism.

Of course, there is also the traditional left, which still wants to transform societies based on the Marxist theory of class warfare. But societies thank you for this, they don't ask for it. In the Western world - but increasingly also in the eastern, southern, poorer countries - almost everyone has "something".

What you don't want to lose. That's why there is no support for socially subversive, "let's take it from the rich" ideas.

The more moderate left, which still thinks in traditional patterns and divisions (capitalists-workers, owners-employees) - rightly so - now sees the enemy primarily in international global capital, so instead of the internationalism previously characteristic of the left, it has itself become a sovereignist. (Which, of course, the globalist left in power likes to call nationalism, since it can use this curse word to demonize those who threaten its own power.)

And in this sovereignist, globalization-critical thinking, the classical left and the modern right agree to a large extent, apparently surprisingly.

Both believe that the nation-states represent the last line of defense against large supranational corporations, which are gaining more and more economic and political power, but cannot be held accountable in elections (or by any political means), and are only interested in their own profit and economic hegemony, and the last bastion of preserving freedom and dignity for people.

Therefore, none of them support the further federalization of the European Union. That is why Viktor Orbán, András Schiffer and László Torockzai say the same thing today on fundamental issues.

Of course, there are still differences. And that's fine. There are more idealistic approaches (either from the right or the left) and there is realpolitik. It's easier to be an idealist in the opposition - and there you have to be! Idealisms give a lot of mental energy. In government and in positions of responsibility, at best they can be dangerous to themselves (the former "people's" wing of MDF, today's Atlanticist "true conservatives", etc.), at worst they can be dangerous to the public (Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, Castro, Chavez, etc.).

Both the idealist and the realist approach - if one does not deny reality - clearly show and justify the sovereignist principle that globalism is not only a dead end, but one of the biggest threats to our current world. Which actually brings other dangers with it.

Because wars are not caused by nation-states per se, but by imperial aspirations. If the states have hegemonic ambitions, especially if they have world hegemonic ambitions. The migration crises were also caused by globalism, the attempt to homogenize the world, and the imposition of the "democracy export". World epidemics (whether accidental or intentional) and the reactions to them are definitely the "products" of globalism. (Moreover, with all of WHO's activities, it is increasingly disguising itself as an entity striving for global hegemony, with motivations similar to those of large corporations.)

Of course, there are those who profit from these dangers, epidemics, wars, and crises. And here we have finally arrived at our days, at the present-day troubles of capitalism.

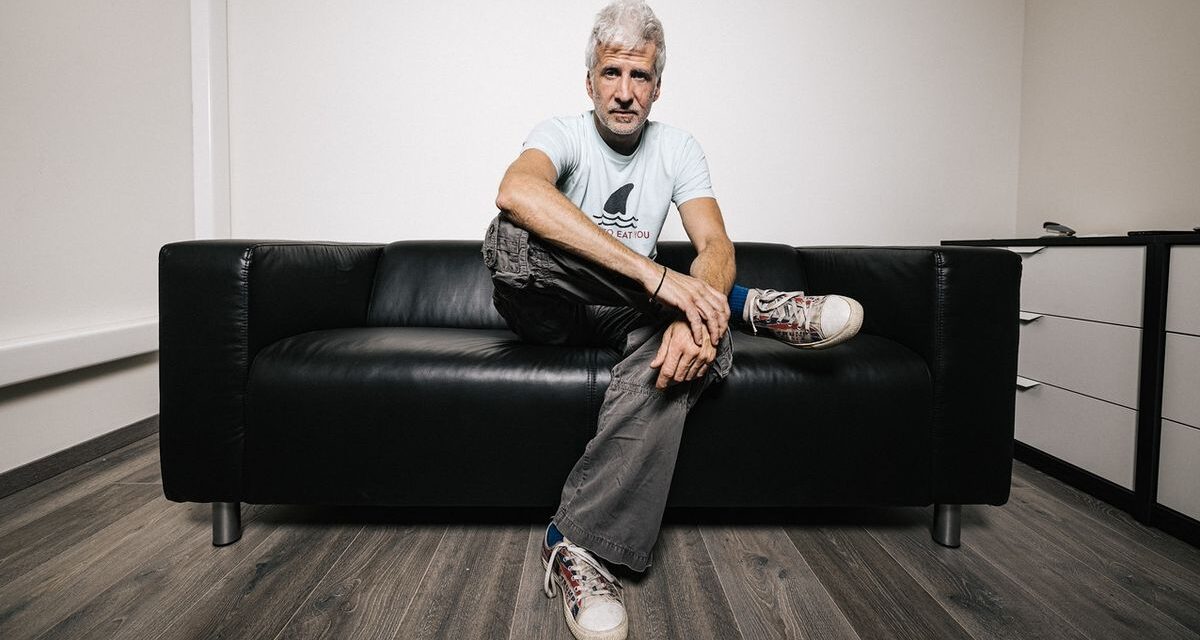

Zsolt Jeszenszky/Hungarian Nation

Featured image: Mandiner/Árpád Földházi