Dead bodies of starved, emaciated people on the streets, cannibalism, millions of victims - this is what led to the violent collectivization and several disastrous decisions of the Soviet party leadership in the early 1930s in Ukraine, one of the most fertile lands in the world.

Ukraine was treated particularly cruelly in the 20th century. century history. The eastern front line of World War I stretched through today's western Ukraine. The Ukrainians found themselves in a conflict between two fires: the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the Russian Empire. Millions of Ukrainians fought on the side of the Russians, and hundreds of thousands in the ranks of the Imperial and Royal Army, the KuK - by definition, not infrequently against each other.

After the Bolshevik takeover of power in 1917 and the collapse of the Russian Empire, a civil war between the Reds and the Whites (and many others) began that lasted several years. Most of the fighting took place on the territory of Ukraine (more recently it is also referred to as a separate war of independence by some historians) - with hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian victims.

In the newly created Soviet Union, into which Ukraine was forced, the consolidating Bolshevik power initially supported the strengthening of the self-consciousness and culture of national minorities (Korenization or nativization) in order to consolidate its system.

As a result, the 1920s brought the flourishing of Ukrainian national culture (by the way, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy also supported Ukrainian nationalism at the end of the 19th century, whose main aspiration at the time was that Ukrainians could use their own language, which in 1863 banned in the Russian Empire, or to unite the nation).

However, the Soviet regime soon began to fear the local version of Korenization, Ukrainization.

They were afraid that the Ukrainians would stick to their nation more than to the Soviet Union, to the communist ideology, so Ukrainization was suddenly replaced by the policy of Russification, which was met with lively opposition.

(The Kremlin perhaps also saw a danger in the fact that the democratic tradition and the love of freedom are deeply rooted in Ukrainian history.)

Stalin's terror, the Great Purge of 1937 in Ukraine, began as early as 1933, as Soviet dissident writer Lev Kopelev said, implying that Stalin had already ordered the purges in the second largest Soviet member republic of the Communist Party, the officials, and the entire society. in its ranks.

However, the famine in Ukraine, referred to as the Holodomor, perhaps surpassed all the evils of the Stalinist regime. According to conservative estimates, 3.5 million, but according to some historians, more than ten million people died of starvation in Ukraine in 1932-33. About half of the victims were children.

The Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin ordered the collectivization of agriculture in 1929. The agitators of the reigning communist (Bolshevik) party forced the peasantry to donate their lands to the community in order to establish kolkhozes.

The population of the extremely high-quality Ukrainian agricultural areas was particularly severely affected. At first, as long as it was not mandatory to enter collective farms (kolektyivnoje hozjajsztvo, i.e. joint farm), farmers did not really join. In 1929 and 1930, tens of thousands of Soviet officials and dedicated Bolshevik industrial workers were therefore sent to the countryside to speed up the process of kolkhozization.

In order to crush the developing resistance (armed uprisings broke out in some parts of Ukraine) and the refusal to deliver crops, the "kulakization" was announced, i.e. the arrest and deportation of farmers who were declared to be well-to-do to the Urals and Central Asia. Many were declared enemies of the system.

Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian "kulaks" were deported, which together with the drought and the disastrous decisions of the Soviet government (the death penalty was ordered if someone was caught "hiding" agricultural crops or stealing collective farm property or grain) led to the tragedy.

Thousands of people were executed, and Soviet secret agents handled requisitions with a diligent hand. In addition to the grain, other food was also taken from the Ukrainian villages, the farmers who resisted were executed or arrested.

Villages that did not reach the prescribed quota could not receive food, could not trade, and even had their money taken away. Due to the bad weather conditions, the crop yield fell anyway, despite this, the Soviet leadership shipped large quantities of grain abroad.

Stalin was particularly concerned about the rebellion in the Ukrainian territories, since a decade earlier the people there had fought against the Red Army in the civil war. There was opposition to Stalin's agricultural policy within the Ukrainian Communist Party, which also worried the dictator.

"If we do not make an effort now to improve the situation in Ukraine, we may lose Ukraine," Stalin wrote to one of his closest comrades, Lazar Kaganovich, in August 1932.

In the fall of the same year, the Soviet Politburo, the communist elite, made several decisions that further worsened the situation in the Ukrainian countryside. Entire villages and towns were blacklisted, which meant that they could not get food. Farmers could not even leave Ukraine to buy food. Despite the spread of the famine, the requisitions continued.

As a result of forced collectivization and disastrous political and administrative decisions, a general famine hit the population in the areas that produced more than half of the wheat crop of the Russian Empire at the time.

Instead of working to organize supplies for the population, the Kremlin did everything to cover up the famine. Foreign journalists were prohibited from entering the affected areas, but – as mentioned above – the local population was also not allowed to leave Ukraine.

People ate what they found: tree bark, grass, roots. Dead bodies of people who died of starvation lay in the streets. People ate their dead, or even their children. Authorities charged thousands of people with cannibalism. The dead were buried in mass graves.

The famine reached its lowest point in the spring of 1933.

If the authorities did deliver grain aid, it was only given to farmers who were still able to work. They gave up on patients.

The population of the cities survived the Holodomor thanks to the food stamp system, but even in the larger Ukrainian cities you could see the bodies of people who had died of hunger in the streets.

According to historians, the independent peasantry was endangered, and with it what it represented: the Ukrainian national consciousness. The "kulaks", used to independence and family farming, would not have been able to fit into the system pushing collectivism to the extreme anyway.

The Soviet secret police also targeted Ukrainian political leaders and intellectuals. Cultural and religious leaders were persecuted as part of the fight against Ukrainian identity. Everyone who had anything to do with the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic, which was proclaimed in 1917 but dissolved after the Bolsheviks took power, was liquidated.

Anyone targeted by the secret police was publicly shamed, imprisoned, sent to the Gulag (the Soviet system of prison camps), or executed.

The Soviet regime hid the famine in Ukraine for a long time. It was forbidden to talk about it publicly, foreign correspondents accredited to Moscow were also instructed not to write about it.

A prominent New York Times contributor, Walter Duranty, did his best to refute the reports of a young freelance journalist, Gareth Jones, about the Holodomor. "Mr. Jones was hasty in his judgment,” Duranty claimed. Jones was murdered under suspicious circumstances in 1935 in Mongolia under Japanese occupation.

Stalin himself took care of covering up the data of the 1937 census. He ordered the arrest and murder of those taking part in the census, as the numbers did not lie, but clearly showed how much the Ukrainian population had suffered.

Famine was discussed publicly during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine, but became taboo again after World War II.

It was not until 1982 that the Kremlin even acknowledged the fact of the famine, although it justified it with bad weather conditions.

Following the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, the word Holodomor entered the public discourse, which is made up of the words holod (hunger) and kiirtani (to exterminate). The Ukrainian poet Ivan Drachs spoke publicly about the Holodomor at that time, regarding how harmful it can be if the official bodies remain silent.

Since the independence of Ukraine in 1991, the Holodomor, one of the greatest traumas in the history of the Ukrainian people, has played a particularly large role in the social memory. Memorials have been erected to the victims across the country, and the fourth Saturday in November is an official day of remembrance.

The Ukrainian parliament (Verhovna Rada) passed a law in 2006 declaring the famine a genocide committed against the Ukrainian people, which was also recognized by Hungary.

And the two houses of the American Congress declared in a resolution that "Joseph Stalin and his entourage committed genocide against the Ukrainians in 1932-33."

Mass starvation and death by starvation did not only affect the Ukrainian people, but millions more in Russia and Central Asia. The Great Soviet Famine lasted from 1931 to 1934, but it claimed the most victims in Ukraine as a result of political decisions that were specifically directed against Ukraine.

"The Holodomor was the first genocide that was systematically planned and carried out by depriving those who produced the food of their food. It is particularly horrific that deprivation of food was used as a weapon of genocide, and all of this was committed in an area known to the world as the breadbasket of Europe," said Andrea Graziosi, professor at the University of Naples.

Ildikó Eperjesi / neokohn.hu

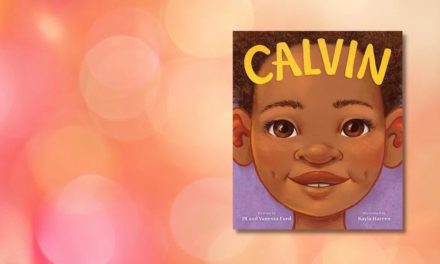

Featured image: Bodies of starved farmers on the streets of Kharkiv during the Holodomor / Wikipedia