The historian Zsuzsanna Borvendég's series was originally published on the PestiSrácok website, but there are certainly those who missed it. But those who haven't read all the parts should also read it again. Knowing the whole picture, can we understand how we got here?

The collaboration between Nazism and Communism did not end with the fall of the Third Reich. Many war criminals avoided prosecution after 1945, for the practical reason that in the developing bipolar world order, their knowledge was important to the great powers - be it technological or even political - and they also wanted to make use of their extensive network of connections. It is not surprising that only a symbolic reckoning actually took place in Nuremberg, a quasi-showcase trial was held, where some of the leading murderers were found guilty, thus passing a moral judgment on National Socialism, but the majority of the perpetrators escaped prosecution . (However, it is gratifying that at least this much happened, since at the end of the Cold War there was no accountability, not even a moral judgment, against the system of communism, which lasted much longer and demanded immeasurably more victims. In fact, it is fashionable to defend the idea to this day.)

"Recyclable" ex-Nazis everywhere

Many high-ranking Nazi officers or functionaries became businessmen and journalists at the beginning of the 1950s, with whom even the "responsible" leaders of the communist bloc liked to work together. Helmut Triska, mentioned in the previous section , did not only play a role in the development of economic interests through the company Atlas, but also operated an information network on behalf of the American intelligence, that is, the CIA used his local knowledge and relationship capital to open a penetration channel on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain.

He collaborated with the most famous former Nazi intelligence officer, Reinhard Gehlen, who defected to the Allies at the right moment. Gehlen recruited his members from the local anti-communist forces in the countries occupied by the Soviets, that is, at the beginning of the Cold War, he represented the most effective information base of the American secret services. With excellent sensitivity, he noticed that with the beginning of the Cold War, the most important fields of reconnaissance were to be found in the cooperations of large industrial companies, financial institutions and especially export-import companies.

Accordingly, he placed his people at these companies, so the financial coverage of the extensive network was also solved, since his colleagues were paid at their cover jobs. Gehlen's people were everywhere in the West German consortia that were Hungary's key partners from the 1960s onwards - Siemens, Klöckner, Mannesmann.

Kurt Becher returns

But Hungarian foreign trade had a more direct connection with the ex-Nazi set. Although Triska was not allowed to enter the territory of the country due to his war crimes, they found others through whom they were able to establish close contact with him and other companies in Germany. One of them arrived in Hungary at the end of March 1944. Gellért Kovács describes him in his book Dusk Over Budapest as follows: "a plump, cheerful and cheerful young man with a well-combed hairdo. This veteran German hunter loved horses passionately, so he joined the SS cavalry, where he later became an economic expert.

His most sophisticated specialty was his ability to blackmail Jews into handing over as much of their wealth as possible in exchange for the promise of better treatment. Ice-cold cynicism hid behind his angelic image, he was not picky about the means to achieve his goal. And now he was here in Hungary, officially to buy horses for the SS, but in reality to get his hands on as much Jewish property as possible, primarily the factories."

image source: Arcanum.hu

Not Becher, but "fate" overtook Kasztner

Kurt Becher , who quickly acquired the most important industrial facilities for the empire, while assessing that the richest Jewish families could benefit him more alive than dead. Together with Rezsó Kasztner , an activist of a Zionist organization, he organized the train that took 1,700 of our Jewish compatriots to Switzerland. Enormous sums had to be paid in return for the escape, which only magnate families could afford, so the vast majority of Jewish citizens watched helplessly as they were let down. The train started and in the end really saved the lives of some families, and it seemed that the organizers also redeemed the ticket for forgiveness.

Becher and Kasztner were exonerated after the war, but Kasztner eventually met his end: an extremist Jewish organization, unable to forgive that the rescue operation was actually a dispassionate business venture, murdered him.

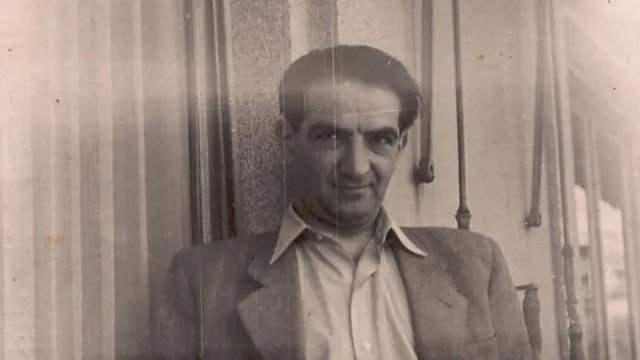

Rezső Kasztner (image source: Fortepan)

He enjoyed the gratitude of wealthy bankers

Becher was not avenged by the Zionists, he died in the nineties as a respected and wealthy businessman.

He got his wealth in part from the fact that he also worked for his own pocket during the confiscation of Jewish assets , but he also enjoyed the gratitude of rich bankers - for example the Oppenheim family - whom he saved from the extermination camps. He partly based his business success in Hungary, as his companies enjoyed a monopoly on the Western distribution of premium quality Hungarian food products such as paprika and honey for many years.

Becher already had a close friend during the war: Karl Bickenbach , and he sold the movables confiscated by Becher, mainly in Vienna and Switzerland. After the war, Bickenbach also founded his own companies and took a huge part of our country's foreign trade with them. From the end of the forties, he became the exclusive representative of Agrimpex, but soon several companies sold their goods through him. Bickenbach was so deeply embedded in the Hungarian trade, that by the mid-1950s, all major exports to the Federal Republic of Germany passed through his hands. The Hungarian companies automatically transferred the commission to him without a written contract, even if the transaction was concluded by the Hungarian foreign traders themselves.

The ex-Nazi asked for compensation for the lost "traffic" due to '56

Bickenbach also got involved in the business of industrial companies, transactions and credit deals, as well as re-export contracts. In 1956, he was able to pocket HUF 1,216,400 in commissions from ten Hungarian foreign trade companies, while in the first three quarters of 1957, he received HUF 1,327,000 in his account. (The average annual salary in Hungary at that time was around HUF 12,000.)

Because of the revolution, Bickenbach suffered damage, as most of the deals signed before October were not realized, so the German businessman had to take out a significant loan. The circles governing the country's finances were interested in maintaining Bickenbach's network, so in order to avoid bankruptcy, the Hungarian partner threw him a lifeline. The ex-Nazi claimed that the revolution and the strikes caused a loss of 300,000 West German marks, which he demanded to be compensated. later played a decisive role in the looting of the country - who at that time was only the deputy head of the Foreign Exchange Directorate of the Hungarian National Bank - suggested that Bickenbach's demand be met , because later on he would have to work for the trust in advance anyway.

(image source: Arkanum)

The country was destitute, but they paid off the ex-Nazi

According to the assessment of Hungarian intelligence, the decision was reckless. Word quickly spread in commercial and financial circles that the Hungarian state had repeatedly granted large loans to Bickenbach, whom it had already helped out in 1953 and 1954. All this despite the fact that Hungary had a modest currency reserve, regularly needed a loan, and searched for credit opportunities. At the moment in question, Hungarian generosity was particularly blatant, since in 1956 the national income fell by 11 percent; in the month of December, there was still no significant production at the heavy industry companies.

The country was at the limit of its solvency, the Ministry of Finance wanted to announce a moratorium on creditors. It is also obvious that Hungary's solvency depended to a large extent on foreign trade, so Bickenbach's assistance could serve the purpose of preventing foreign trade companies from losing their West German markets. It could also be a reassuring message to the creditors: we are solvent, the repayments could be rescheduled quietly, soon everything will return to the old way, we are the masters of the situation. However, Bickenbach's support was frowned upon by circles that were also important economic partners of communist Hungary, so it was necessary to carefully communicate what had happened to them. Gerhard Todenhöfer , the deep-rooted Nazi merchant, was such an opponent

Goebbels' liaison also saved himself

Gerhard Todenhöfer also started his career as a functionary of Adolf Hitler's At the University of Marburg, he was the leader of the local youth organization, thanks to which he was promoted to a high position in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at a young age: as a government adviser, he was a liaison Joachim von Ribbentrop and Goebbels. served as a political officer alongside Field Marshal Ferdinand Schörner, who was later convicted as a war criminal After 1945, Todenhöfer was right to fear that he too would end up on the dock, but he was not brought to justice, even though during his foreign service he was the deputy head of the department responsible for Jewish affairs. He owed his survival to his excellent network of contacts; his well-wishers even prevented him from being questioned as a witness.

Todenhöfer started dealing with foreign trade after the war and established relations with Hungarian companies. Besides Becher, he was the other most important partner of Monimpex, he handled half of the honey exports to West Germany, but Terimpex and Hungarofruct also had the ex-Nazi businessman among their contractual partners. Bickenbach's extensive monopoly in Hungarian exports to the West Germans obviously affected Todenhöfer's interests, and he voiced his objections at a diplomatic level meeting.

Todenhöfer's opinion could not have been indifferent to János Nyerges . Todenhöfer had good connections to German government circles Georg Kiesinger , who at the time was the chairman of the committee responsible for foreign affairs in the lower house of the parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Georg Kiesinger (center) and Todenhöfer in Austria (Photo: Fr.de)

The acceptance of the Kádár government, which was struggling with legitimacy problems, with the Western powers was a central issue in the months following the revolution, and Kiesinger and Todenhöfer expressed their concerns as early as the spring of 1957 due to leaked news about reprisals. Statarial judgments aroused the resentment of Western public opinion, so they warned Kádárek: it is not necessary to make such judgments, or if they are made, it is not necessary to make them public.

Nyerges replied that "these are the so-called outrages are not sincere, and just as the Germans are not bothered by the kind of democracy in, say, Spain, Iran or South Africa and happily trade with these countries, they should not be bothered by the domestic political situation in Hungary either".

They rejected the criticism of the ex-Nazis

It was obviously easy for Nyerges and the Hungarian foreign affairs officials to reject the Germans' criticisms, since they were formulated by people who assisted the Nazi genocide not so long ago. At the same time, the German delegation also showed a strong receptiveness to the dusting. They were connected by political interest: the Hungarian side believed that Kiesinger could be a candidate for an important government position in the near future, so they could find a politician who takes Hungarian economic interests into account among the highest decision-makers of the Federal Republic of Germany. Kiesinger was also happy with all kinds of apparent foreign policy results, since Adenauer was not convincing enough for him to see his plans for the future secured: he applied for the chancellorship.

We can see that a significant part of the business relationships established in the 1940s were made with former officials of Nazi Germany , and this system of relationships was also inherited by the early Kádár system. While Kádár and his henchmen described the freedom fighters of 1956 as "fascist mobs", they were doing business with real Nazis.

(to be continued)

Source: PestiSrácok

Author: historian Zsuzsanna Borvendég

(Header image: Northfoto)