We are stuck in mundane reality, and mundane reality is sticky. This is what we did to ourselves. Delirium instead of prayer. Real instead of true.

In January of this year, I was proud at the opening of our new Petőfi permanent exhibition. We sent Sándor on a triumphal journey, he got up and walked, our two-hundred-year-old Sándor is so present from the past that it lifts him up.

Then came Alaine Polcz. Ouch. You can feel it.

Noble Ágnes the Great. Species.

Now here are the Peters with the scandal of existence. Esterházy, Nádas, Hajnóczy.

What should we do with the fact that one Péter, born in the same year, is 80, and the other is almost 40? Is the curator allowed to call Péter when he no longer knows Péter?

And what to do with shame?

Because we know, of course, we know that there is no clean slate. Reason knows.

Tamás Cseh follows, and Géza Szőcs looks back at us quietly in autumn.

The shame seeps in and eats you up.

We are ashamed of the XX. for the century.

Two world conflagrations, two dictatorships and the terrible silence that Imre writes about while the firing squad reloads.

How could we leave it? How could we allow everything that the above-mentioned people tell through their stories? How could we, the Europeans, the Westerners, the Hungarians, let it go?

Who spoiled the XX for us so much? century?

Recently, there is a lot of talk about collective responsibility and its limits.

Why we have to take responsibility. Therefore, that is, our XX. for our century, our XX. we must certainly take responsibility for the European part of our century. If Petőfi is present from the past, then Alaine, Ágnes, the Péterek, Tamás and Géza are present from our present.

Present time, present space, happening here. It happens to us.

The scandal of existence is not about falling into sin. Crime requires metaphysics, but here it is only physics, time and space, concrete. It is no accident that the Peters are so concerned with the body and perception. It is not by chance that they metaphorize material taboos.

The scandal of existence is that we are stuck in ordinary reality, and ordinary reality is sticky. This is what we did to ourselves. Delirium instead of prayer. Real instead of true.Shame instead of remorse.

Petőfi has a myth, we have stories. We have stories that we feel on our skin, with our skin. We can't, we can't get away from reality.

But these stories must be told. Someone has to tell me.

And if some people take the courage, because writing takes courage, then the rest of us must read these works.

That is why we initiated the posthumous DIA 100 a few years ago. In other words, in addition to the membership of the "official" Digital Literary Academy, we started to collect and make available free of charge the works of a hundred Hungarian writers who have already passed away, who for some reason did not enter the wider public's consciousness, but who had the sticky XX. century reality had its chroniclers and shapers.

(…)

We must remember. It is old knowledge that only remembering, i.e. reliving, can establish the future present.

If we don't forget to be ashamed, then and only then do we have a chance that the XXI. century, we will not make the same mistakes against ourselves again.

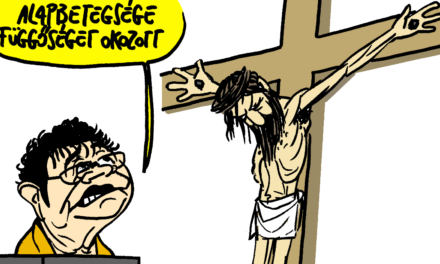

Because this is the biggest lesson of the scandal of existence: the Good Lord does not save us from ourselves.

helyorseg.ma

Featured image: Tibor Illyés/MTI