"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!" Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated

From Borsi to Munkács, from birth to the mother's new marriage

We have already mentioned the birth of Ferenc Rákóczi and some events of his childhood in the previous sections. Born on March 27, 1676, in Borsi, II. In the time of Ferenc Rákóczi, parents loved and nicknamed their children, and this was especially true for noble families. The life, safety, and protection of young children were valued at the beginning of the 18th century because, after the expulsion of the Turks, the shortage of people caused by genocide had to be made up. The circumstances in which a child spends the first 10-12 years of life are of great importance in the child's development - this has now been scientifically proven. From the time little Rákóczi was born, he was literally exposed to mortal danger several times. Male children of aristocratic families were especially vulnerable to premature death.

The boy, who was the only and last male member of the family, was exposed to even greater danger. Among them was II. Also Ferenc Rákóczi.

The reason, of course, was the acquisition, inheritance, and guardianship of huge estates. This Viennese tactic was already practiced a century earlier, and it was the subject of, among other things, the treason trials.

The Rákóczi family lived in Munkács in 1677, where, in addition to the mother, Ilona Zrínyi, the paternal grandmother, Zsófia Báthori, also settled. There were many disputes and antagonisms between the two strong-willed, but sharply different women in their way of life. The children, Julianna and Ferenc, were not affected by this contrast, because they only received love and the conscious upbringing of their mothers and grandmothers. After the early death of the father, Ferenc I. Rákóczi, the Hungarian-hating emperor Lipót I (1655-1705) became the guardian of the children and thus the master of the huge Rákóczi estates.

Thanks to the quick action of Zsófia Báthori and Ilona Zrínyi and their influential court supporters, Ilona Zrínyi was still able to exercise guardianship. It is true that this left the young widow with the responsibility of managing the properties in a catastrophic state and making them profitable. In the misfortune, the luck was that the children could stay with their mother. Meanwhile, the war between the Kuruc insurgents and the imperial troops was already raging. The cruelties of the court did not deter the disaffected insurgents. On the contrary, more and more people joined the Kurucs. They won a number of small victories in the beginning. Focal points of resistance have formed. Among them was the seemingly impregnable fortress of Munkács. However, given that Munkács stood at the crossroads of the war roads, there was never peace here. Ilona Zrínyi therefore moved with her family to the more distant but safer Regéc castle at the end of 1677.

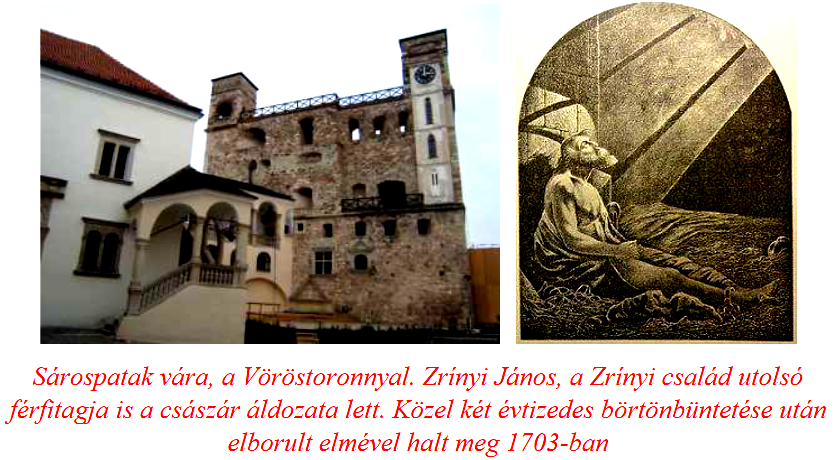

After a few months, in March 1678, the family moved to Patak Castle with the then two-year-old "prince". Here, Ilona Zrínyi was able to form her court alone, without Zsófia Báthori. Little Rákóczi lived his real childhood in a stream, where he was influenced by colors, objects, cheerful sounds, music, a variety of games, and a diverse linguistic environment. (See section 49.) A child's first great experience is the Vörö Tower built by his great-grandfather, the thick walls of the castle, and the sight of the river Bodrog below. It was here that Rákóczi first experienced what would accompany him throughout most of his life, being surrounded by a foreign language environment. Despite this, he remained steadfastly Hungarian in his heart and soul. In Patak, the rich world of tales, histories, and poems was fixed in him, which we can read about, among other things, in his writings entitled Confessions and Memoirs. In the previous chapter, we mentioned that Rákóczi understood and spoke nearly ten languages. This was accompanied by the fact that he knew the culture, politics, religion and customs of most European countries. Childhood prepared him for this knowledge. Ilona Zrínyi did everything for her children's mental development, health, and safety. He took care of their meals, their constant supervision, their studies, and even their clothing. Until he was five years old, the child Ferenc was looked after by the women who raised him. After that, however, the nobleman György Kőrössy of Zemplén, an old loyal supporter of the Rákóczias, was the butler of the young prince. Literally for his life, because there were more than one attempt to poison the young Rákóczi.

In 1678, you could hear the name of Imre Thököly more and more often, who occupied a significant part of the Highlands at the head of the Kuruc armies. By taking possession of the mining towns, Imre Thököly, who became known throughout Europe, created the economic foundations for the successful continuation of the freedom struggle. The nobles of the highlands, serfs, Végvár soldiers, and lodgers stood by him en masse. In the summer of 1678, Ilona was secretly visited by her brother, János Zrínyi, who was an imperial officer, but the court distrusted the son of Péter Zrínyi, who was executed in 1671. János Zrínyi was later captured by the Kurucs, where he met Imre Thököly. This meeting certainly also contributed to the fact that the Lord of the Highlands visited Ilona Zrínyi in February 1680. During the short visit, they agreed that the only way to protect the security of their entangled possessions was to get married. Zsófia Báthori was against the marriage, as she still had not given up on her grandson becoming the king of Poland. Furthermore, she did not want her son to be succeeded by another husband, and moreover an evangelical one. However, the elderly princess died this year, so Ilona Zrínyi was free to decide. After long preparations, the bright wedding was held on June 15, 1682.

The six-year-old child was not supported by his mother's new marriage, as he did not know his father, Ferenc I. Rákóczi. Little Rákóczi really didn't like Count Imré Thököly - the tall, good-looking, friendly one. However, Thököly paid attention to the education of his stepson, while also teaching him many important things.

The beginning of the school of life

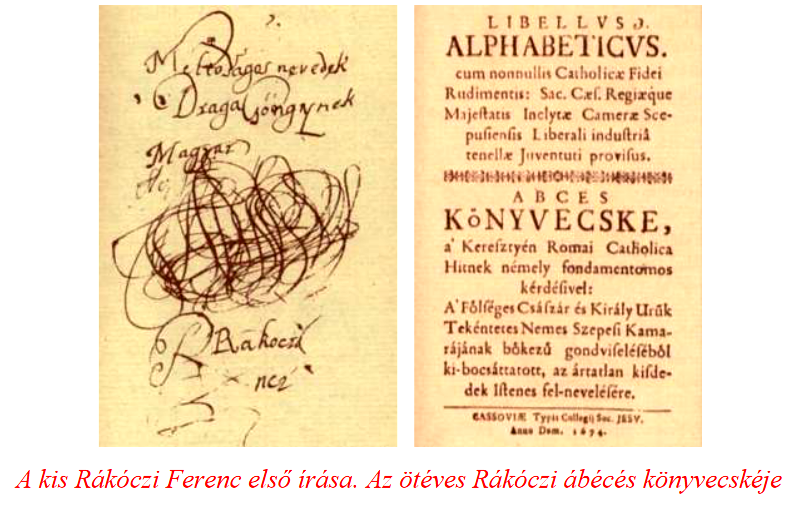

The child attended the beginning of the school of life with György Kőrössy. It was thanks to him that throughout his life he was able to communicate with people with whom the nobles otherwise did not come into contact. The chamberlain was constantly conducting business affairs, meeting various people, speaking different languages, and little Rákóczi saw and heard all this and learned a lot from it. The six-year-old child learned the art of spelling from the Franciscan monk János Bárkány. Ilona Zrínyi did not let the child go to school in the town of Munkács, little Ferkó was taught within the safe castle walls. The elementary school alphabet book of Fejedelemf contained the Lord's Prayer, the Hail Mary, the Faithful, the Ten Commandments, the table blessings, the morning and evening prayers in beautiful Hungarian. This little book was the first Latin-Hungarian dictionary from which the young Rákóczi learned the language.

In his Confessions, Rákóczi writes about his first school years: "I was often punished because I was too lazy to study and indulged myself too much in children's games with weapons and war." But he was also aware of that when he wrote that:

"My teachers formed in me the morals appropriate to our rank and prepared me to pray."The school years associated with the institutions began when he was permanently separated from his family. The twelve-year-old is taken to a boarding school in the Czech Republic with the aim of re-educating him, to make him forget that he was ever Hungarian. Before that, however, he had to learn even the occasional dangers of the school of life.

in Thököly's camp

The Kuruc uprising in 1683 was full of continuous battles. Thököly wanted my seven-year-old son to smell a little gunpowder, as he called it, and took him with him to the war camp. The fact that he lived in a tent in Cseklés near Bratislava, that he met famous people coming to the embassy, that he had to live on simple camp food had a great impact on the child. He had to wake up early, experienced the cold, rain, and hunger. gun noise. It was then that he first saw prisoners, crying mothers, the wounded, and the dead.

After the Battle of Kahlenberg, which took place in the camp on September 12, 1683, little Rákóczi's life was in danger. The Polish king János Sobieski and his allies won an overwhelming victory over the Turks. The fleeing Ottoman army stormed through the Csekléz camp in such a way that the tents fell into ruins. György Kőrössy saved little Rákóczi's life by hugging him, running with him out of the collapsing tent and taking him to a safe place. The life of the last male member of the Rákóczi family was in even greater danger when they tried to poison him more than once, since the huge estates and the princely title were a thorn in the court's side. However, György Kőrössy cooked for him separately, and at joint meals he was always the first to taste the food placed before the child. There was a case where György Kőrössy was offered a large sum of money if he would let the assassins near the child. From then on, the chamberlain guarded his client even more vigilantly, not letting anyone near him. Thököly was ill and little Rákóczi returned home to Ilona Zrínyi in Munkács unharmed. The political and military situation was ominous for Thököly, as the Turkish, French, and Polish kings distrusted him, and Vienna was openly hostile to the Kurucs.

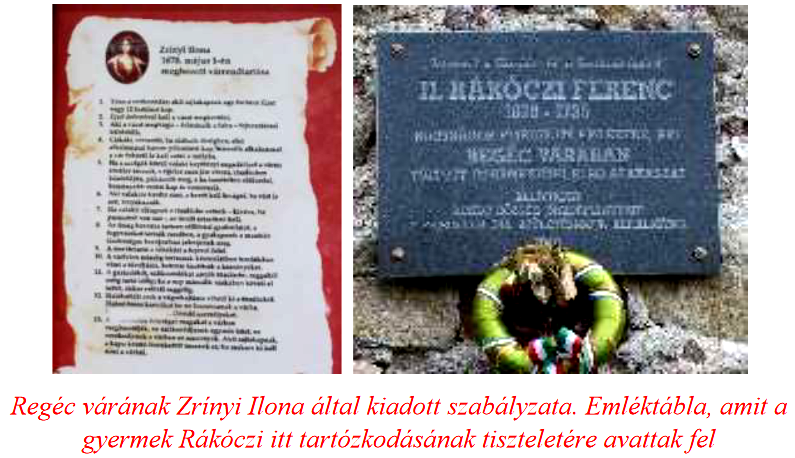

Rákóczi spent the year 1684 in Regéc, far from the noisy world, where he spent his time studying. However, the peace and tranquility did not last long. In 1685, Ilona Zrínyi fled with her children from Patak once again to the safe walls of Munkács. In the meantime, Imre Thököly's affairs were getting worse and worse. The emperor sent General Aeneas Caprara to Upper Hungary, whose main task was to remove Thököly. In his final desperation, the Kuruc prince looks for help from the Turks. He went to the castle to negotiate, but the Pasha took him prisoner. Ilona Zrínyi was left alone. In October 1685, it became clear to him that, arriving under the imperial general Munkács, he demanded the surrender of the castle. Ilona Zrínyi could do nothing but follow the example of her ancestors, and without revealing her husband's kuruc politics, organized herself to defend the castle.

The fall of Thököly

At the end of the 17th century, in the summer of 1684, the troops of the Holy League began the siege of Buda, which had been in Turkish hands since 1541. (The alliance established in March 1684 at the initiative of Pope Ince XI was formed by the Kingdom of Poland, the Habsburg Empire, the Republic of Venice and the Papal States.) Thököly tried again by switching to the side of the Christian alliance, but the imperial troops suffered a heavy defeat in September 1684 they were measured against the lord of the Highlands. Vienna did not want to strengthen the Christian alliance, but to acquire the Highlands - with all its treasures. The appearance of János Bottyán is connected to this period, who served in the imperial army until 1703 and rose to the rank of colonel. Bottyán, who was otherwise born in Esztergom, had a lion's share in the defense of Esztergom in 1685, when the Turks wanted to retake the castle.

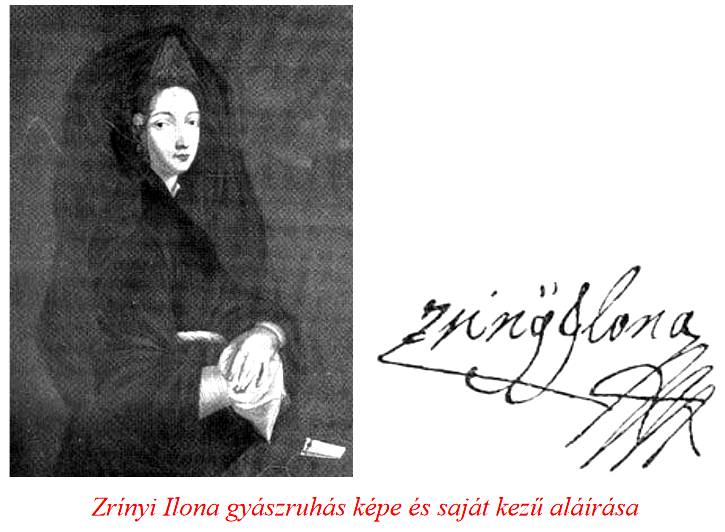

After the recapture of Érsekújvár in 1685, the imperial troops took back the castles and towns in the highlands from the Turks. Thököly was freed from his defeats and from the captivity of the Pasha of Várad, without power, money or an army. He didn't even have the opportunity to return to his wife, Ilona Zrínyi, in Munkács. On Munkács, which was besieged by the Habsburgs from December 1685. While the siege of Buda was taking place, the decisive part of the northern region, which previously belonged to the principality of Imre Thököly, fell into the hands of Vienna. Munkács was the only one who defied the emperor's superior force. The defense of the castle was managed by Ilona Zrínyi, who was revered as a hero throughout Europe.

Heroic act of Ilona Zrínyi

Kassa also fell, and the imperial troops often carried out cruel reprisals. Thököly in Turkish captivity, János Zrínyi in the emperor's dungeon, misery and hopelessness in the country. Only the castle of Munkács could be the consolation, the last hope. The castle had already been prepared for defense against the siege in previous years. The construction was supervised by the castle captain András Radics.

On Pentecost 1686, the besiegers withdrew from Munkács Castle. However, the town of Munkács was looted, set on fire, and everything was lost. In the midst of these tragedies, Ilona Zrínyi was expecting a child. They kept in touch with her husband, Imre Thököly, through couriers. When the heroine gave birth to her child, Buda was freed from 145 years of Turkish rule. However, the child did not survive, the birth took its toll on the mother as well.

Ilona Európa Zrínyi's name was heard when the heroic Hungarian woman who stood alone against the Habsburg arbitrariness was mentioned. The emperors committed many atrocities, but the most frightening news came from Eperjes. The blood bath in Eperjes shocked even the battle-hardened people of the era who had seen many deaths. Antonio Caraffa, the executioner of Eperjes, tortured the nobles of the town, about three hundred evangelical citizens, and among them he publicly executed 25 innocent leaders of the town.

"First, the right hand of the tortured was cut off, then they were beheaded, and then the mutilated corpses were quartered. The dismembered bloody bodies were nailed to the main square and in the courtyards, the whole city was horrified."

All this happened at the behest of "cultured Vienna" between March 5 and May 9, 1687. (The cruel execution of vezér Koppány was embedded in the events written by foreign hands in Hungarian history teaching as a barbaric Hungarian act. Which was more than likely not true! But the story of the blood bath in Eperjes at the end of the 17th century, which is based on authentic descriptions, is less well known.)

Little Rákóczi's eleventh birthday could not be celebrated in the Münkacs castle under these circumstances. The heroine, who was also suffering from childbirth, sent her emissaries to many European countries to help, but she received nothing but nice words. Knowing the Hungarian history of the previous centuries, we cannot be surprised by this, it has always been like this, and it is like this to this day. Munkács' defenders were getting more and more exhausted, they ran out of ammunition and food, and they could not pay the soldiers' wages. ARC. King Louis of France sent some food, but that was all, no one else helped. (For the Sun King, the fact that the Hungarians had tied up part of the military forces of their biggest rival, the Habsburg Empire, meant that much.)

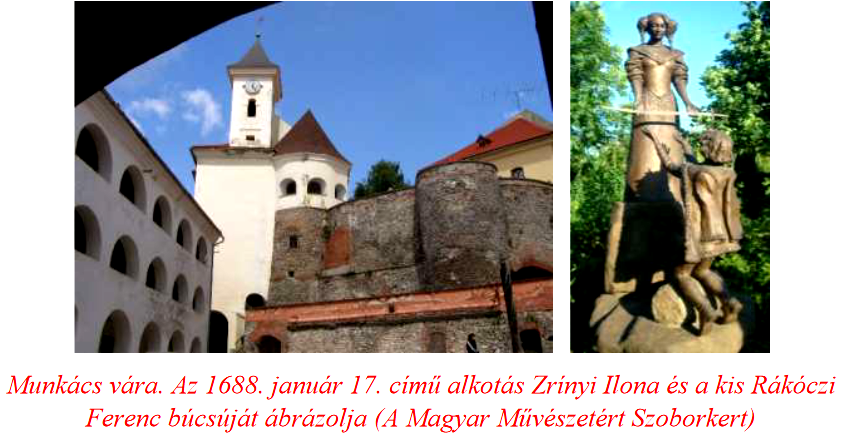

Ilona Zrínyi was forced to surrender the castle on January 17, 1688. However, he managed to get Munkács' defenders granted amnesty, and the Rákóczi property could remain in the name of his children. This was vitally important. After all, if it doesn't happen like this, II. Ferenc Rákóczi's life and political career would have taken a completely different direction. Ilona Zrínyi was separated from her children not in Munkács, but after a long, weeks-long journey, arriving in Vienna. The family arrived in Vienna on March 27, 1688, the birthday of little Rákóczi. They were made to wait for hours in front of the city gate, which in itself was blood-curdling. Moreover, the Viennese flocking to the news of their arrival humiliated the ancient princely Hungarian family with intrusive curiosity and cynical comments. The descendants of the Zrínyis and Rákóczias, who gained a European reputation, bore the humiliation with dignity. Not knowing at the time that the twelve-year-old child sitting in the carriage would later become one of the biggest figures in the Hungarian freedom struggle against the Habsburgs. However, fifteen years had to pass by then.

School years

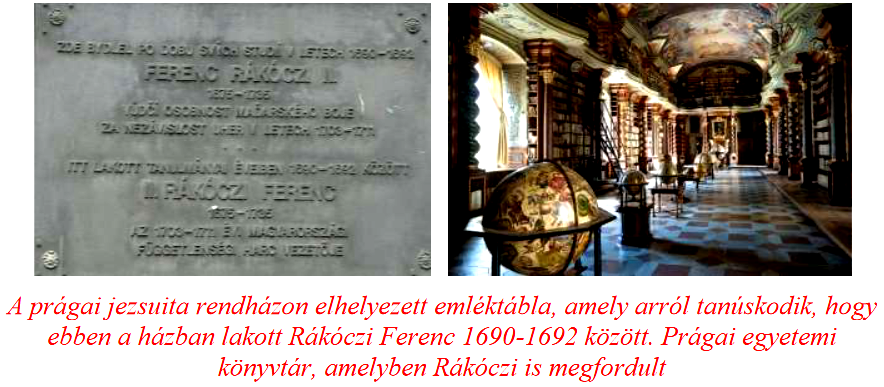

Twelve-year-old Rákóczi was separated from his mother and sister after the family arrived in Vienna. The emperor's arbitrariness forced the young man to attend a Jesuit school in Bohemia, Neuhaus, which was reserved for the noblemen's children. The school's teachers and fellow students welcomed the prince's offspring with love and respect. A color show and a banquet were organized for him. According to one of his teachers, Rákóczi was highly regarded in Neuhaus from the beginning because of his perfect knowledge of Latin, his education, his stature, his eclectic taste, his clothes, and his charming manner.

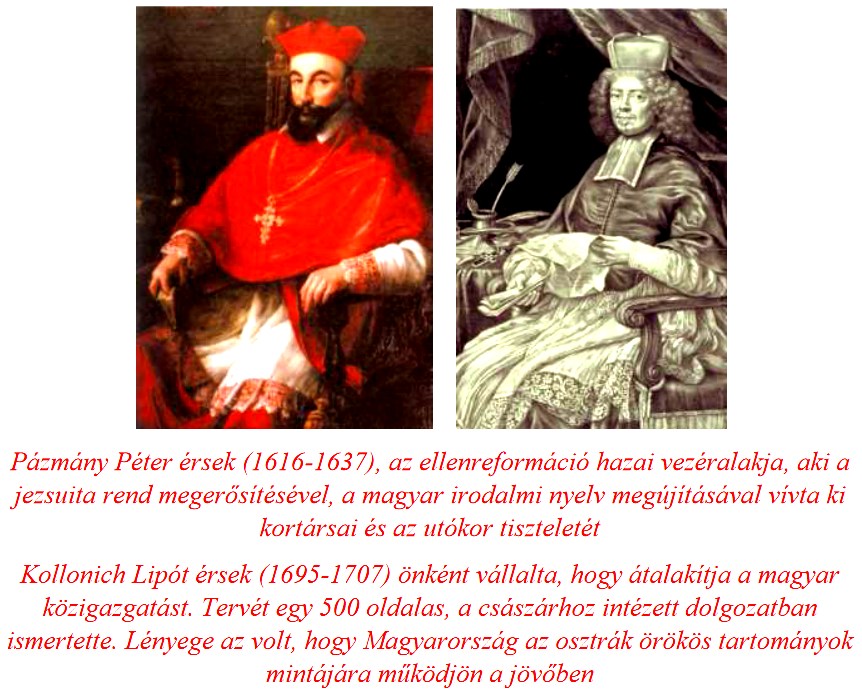

Emperor Lipót appointed Archbishop Lipót Kollonich, who was only mentioned with anger by the Hungarians, as Rákóczi's guardian. The Kollonich, about whom we already noted in the previous chapter, how he thought about our country:

"I will first make Hungary a prisoner, a beggar, and finally a Catholic."

His politics were characterized by the organization of an informant network, the adoption of economic measures that affected Hungary, and the merciless persecution of Kurucs and Protestants. Unfortunately, Kollonich did not follow the policy of his great predecessor, Péter Pázmány, who led the church with patience, the power of good words and preferably not with the weapon of violence.

It was in this political atmosphere that Ferenc Rákóczi arrived at a school in the Austrian Empire, where everything was done to make the Hungarian prince an Austrian. The Jesuit monks set about re-educating the child with great patience and determination. First, his beautiful Hungarian clothes, carefully selected by his mother, were replaced with German clothes. Over time, she had to part with her long, wavy hair, her lovely food, and her home habits. However, the out-of-date Jesuit upbringing did not affect the young man. The distorted version of Hungarian history - which they tried to instill in the young man for years - did not make a big impression on Rákóczi. He remained Hungarian in his soul and feelings, although he changed a lot based on his external features. The most lasting experience of the Neuhaus years was the hospitality of the Czech owner family of the region, the Counts Slawata. They liked the young Hungarian gentleman for his own sake, but the good relationship was also strengthened by the letters written from Vienna to the worried mother. Rákóczi enjoyed being in nature and being surrounded by weapons and horses. Here he learned to hunt as a companion of the count, which he pursued passionately throughout his life.

Rákóczi often played chess with the director of the college, Father Zimmermann, who liked his smart student for that reason. At school, he preferred to be in the physics room, where he conducted experiments and learned to use astronomical telescopes. During the two years he spent here (1688-1690), he mastered the science of turning in the carpentry workshop, since the young Rákóczi liked to work with wood the most. He will take advantage of this during his emigration years in Rodost. However, the school also managed to impose certain qualities on the young man, which were shown, among other things, in the sometimes clumsy, difficult Hungarian of his letters. However, the two years were not enough to train him to become a Jesuit priest according to the original plans. He also had well-intentioned educators who, seeing Rákóczi's independent thinking, did not force him to become a priest.

One of the most beautiful memories of his high school years is the literary work of poetry teacher Guttwirtt Menyhért, which he created in honor of his famous student. In the text of the work embellished with Rákóczi's portrait, we can read that "if we look at this intelligent, noble, beautiful face, we understand that Rákóczi was loved by everyone, welcomed everywhere, and was never saddened, because he did not hurt others either." During the summer holidays, he took long trips in the mountains, visited the towns and monasteries where Jesuits lived, who received the student with great respect. It was Rákóczi's custom to give jewelry, souvenirs, and pearls to those he liked, those who taught him.

At the age of fourteen, Rákóczi was sent to Prague by his guardian, Archbishop Kollonich, to continue his studies at the university there. His accommodation was in the convent of the Jesuits in Prague, from where he reached the university building by walking half the city. In the first year, he studied mathematics, logic, and metaphysics. This latter subject - which he did not like because he saw no use for it - dissected the system of philosophy related to theology. On the other hand, he loved mathematics, and then, connected to this, the arts - architectural art, painting, geometric figures - captured his interest. In the second year, he studied physics and ethics. His Jesuit teachers held him so tightly that after a while he lost contact with the civil world. He avoided entertainment and companies, and was only bound by the secrets and beauties of nature, which he considered God's creation. He despised alchemy, astrology, and superstitions, which was partly the result of the strict Jesuit university years in Prague. Kollonich's plan seemed to have come to fruition. You couldn't even recognize the young man who lived in the German way, who even three years earlier stood out among the young Hungarian nobles with his dress, wit, skill, and beautiful Hungarian speech.

Ilona Zrínyi and Julianna Rákóczi

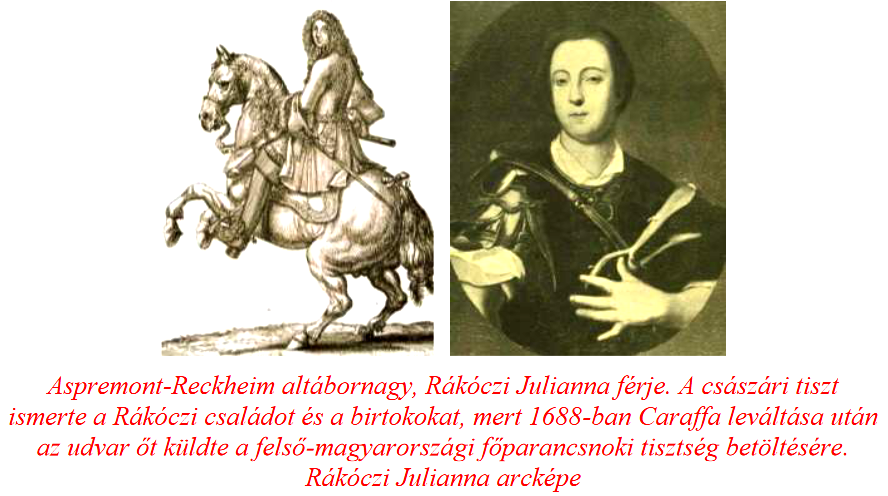

Ferenc, busy with his studies at the Jesuit school, was isolated from his sister and mother. The then eighteen-year-old Julianna was escaped from the Orsolya convent in Vienna by the forty-eight-year-old Count Ferdinand Aspremont-Reckheim, and secretly married her in 1691. The fact that nothing was leaked about the antecedents of the marriage was primarily due to the excellent organizational skills of Ilona Zrínyi. Emperor Lipót and Cardinal Kollonich - who thereby lost his guardianship - imprisoned the husband in their impotent anger. However, after some time, the court was forced to recognize the marriage. Julianna gave birth to seven children, and the Rákóczi family lived on in her descendants.

Ilona Zrínyi's fate also changed. Thanks to a prisoner exchange, he was able to leave Vienna for good in 1692, but he also had to leave his beloved country, Hungary. She ate the bitter bread of exile in Turkey with her husband, Imre Thököly, who had already failed for good. He never saw his daughter, his son, his country again. The emperor did not allow his children, who were then of legal age, to leave with their mother. Part of the inhumanity of the Viennese court was that they did not even allow the children to say goodbye to their mothers. What's more, the events were staged in front of the two children in such a way that Ilona Zrínyi became a traitor to her country, that's why she went to Turkey. The intriguers at court also succeeded in turning the two children against each other over the distribution of the family inheritance. However, this opposition was resolved later, in a fraternal way.

After finishing his studies, Rákóczi lived in Vienna in the house of his brother and his husband, Count Aspremont. However, it was not easy. After all, in 1692 he could only get to Vienna, where he could finally meet his sister after four years, by tricking Kollonich's vigilance. It turned out that the sixteen-year-old had almost forgotten the beautiful Hungarian language of his ancestors. His sister persuaded him to stop his completely unnecessary studies and live his own life. And so it happened. After a while, Rákóczi forgot about the noisy, turbulent life in Vienna. The previously aloof young man took a liking to entertainment and social life, which earned Kollonich's anger and dislike again.

He had his first love experience in his sister's palace with Eleonóra Strattmann, who was, however, the wife of Ádám Batthyány. He got rid of the scandal by taking Kollonich's intervention on a tour of Italy, which later became one of the defining experiences of his life. Ferenc Rákóczi already admired the wonderful buildings of Venice in 1693.

Author: Ferenc Bánhegyi

Cover image: Historical flags

The parts of the series published so far can be read here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28., 29/1.,29/2., 30., 31., 32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46., 47., 48., 49.