"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated

II. József's decade rich in events

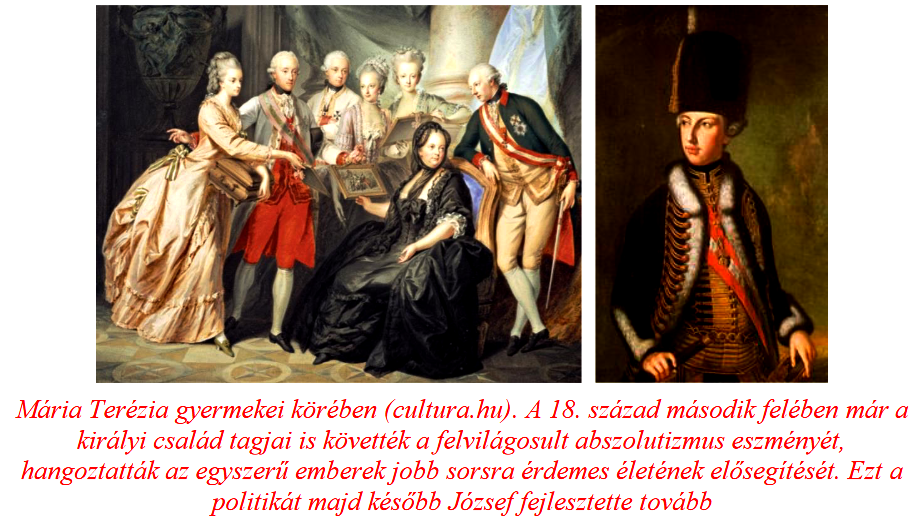

The family got its name from the Habsburg castle (Habichtsburg – Héjavár) located at the northern border of today's Switzerland. One of the largest and most influential ruling houses in Europe split into two branches over the centuries. To the Austrian branch and the Spanish branch. However, II. Károly died in 1700. (This was followed by the already discussed war of Spanish succession, of which the Rákóczi War of Independence was also a part.) The Austrian branch also met its fate when Mária Theresia died in 1780. Austria, however, from the House of Habsburg-Lorraine II. With the accession of József to the throne, it continued to develop, the price of which, as in several cases during the past centuries, was paid by the Hungarians.

According to historical legend, József, who was born on March 13, 1741, became a "protagonist" in Habsburg politics when he was six months old. At the national assembly in Bratislava, the young empress, rightly afraid of the collapse of the Empire, asked the Hungarians for help. From those Hungarians whose eight-year struggle for freedom was drowned in blood three decades earlier. Mária Terézia, with the crying baby in her arms - and this is truly the world of legend - moved the Hungarian lords so much that they voted for the requested support for Vienna, which was struggling with a serious crisis. At that time, on September 11, 1741, the famous sentence was uttered: Vitam et sanguinem!

Even as a child, József Habsburg-Lorraine was a stubborn individual who did not tolerate contradiction. He didn't listen to his teachers, despite the complaints he received, he only followed the path he chose. He was greatly influenced by the ideology of the Enlightenment, which then shaped his economic, cultural, educational, and religious policies. His economic vision was chamberism, which aimed to benefit the chamber and increase the income of the state treasury. It was nothing but the Austrian version of French and English mercantilism. The bottom line is that exports far exceed imports. In the case of the colonial countries, this worked well, as the maritime great powers used their advantage stemming from their yoked human and raw material base at their disposal. In Austria, it was not so simple. Vienna had to ensure the benefit of the chamber through taxes and royalties (income collected by right of majesty, which was collected by the ruler in addition to the regular tax). For this, the citizenry, industrial production had to be strengthened, and the population had to be increased. "Where there is population, there is money." was voiced in the Court. This was an imperial principle until now, but from the end of the 18th century, it became the distinguished direction of economic policy. Hungary played the role of the "pantry", and the western regions - Austria, the Czech Republic - played the role of the industrializing, urbanizing, bourgeois region.

József stood out even in the list of "colorful" rulers of the Habsburgs with his controversial figure and behavior. This was due to the aloofness he was born with, as well as the subordinate position he spent with his mother for many years. It is true that he became co-ruler of the Empire in 1765 after his father's death, but he could not implement his own policy with his strong-willed mother. He had to wait another fifteen years before he could truly rule. In 1780, he almost burst into the life of the Empire with his plans, ideas, and repressed emotions born in a decade and a half. (Despite many quarrels with his mother, when Mária Theresia died, József mourned her sincerely.)

Back in 1763, József wrote his conception of the state entitled Álmodozazoks, in which he explained that he wanted to achieve unlimited absolute power after ascending to the throne. When he came to power at the age of forty, he could not have known how much time he had to put his countless plans into practice. His reign was characterized by impatience, the issuance of often thoughtless, far-reaching plans, and the disregard of economic and social conditions. He did all this by reducing the number of courtiers to a fraction, saying that it was also necessary to save.

The life of Prince Joseph before his accession to the throne

The development of his character and personality is well exemplified by the way he prepared to rule. He lived a puritanical life. He avoided balls, all kinds of entertainment, he did not seek the favors of women. He felt good when he was alone. He was greatly influenced by the Enlightenment, but he could only imagine it within the framework of Habsburg absolutism. It is characteristic of Húmán's thinking that, for example, he opened the imperial gardens, which had been strictly closed until then, to the common people. Among other things, he disbanded the Hofburg bodyguard and created a smaller but more qualified corps.

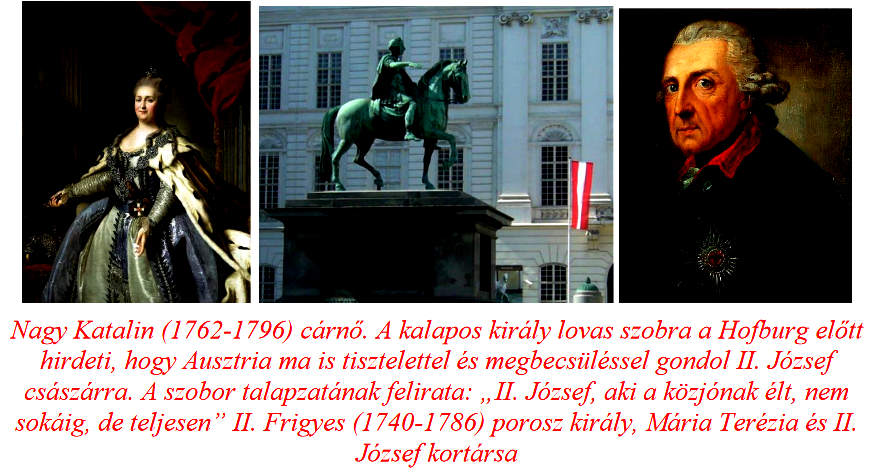

He spent part of his time visiting the provinces of the Empire. For example, he visited Hungary in 1768 and 1773. Incognito, under the name of Count Falkenstein, he also visited famous places in Italy, France and the German Empire. He met Emperor Frederick the Great, whom he regarded with great respect, and what's more, he saw him as his teacher.

During his travels, he made precise descriptions, drawings, and notes about everything. He forbade it to be celebrated anywhere, that he would be welcomed with a fancy dinner. Most of the time he did not even accept the invitations of the nobles, he stayed in the simplest inns. These gestures, as well as his simple, sometimes shabby clothing, served two purposes. One to increase his popularity, the other to set an example of avoiding a spendthrift lifestyle. Some of the latter, in their later decrees, had the opposite effect than what was intended. The trampling of natural, ancient rights in the mud gave rise to discontent. (For example, it should be mentioned that he prohibited coffin burials during funerals, citing the need to save money.)

József's first wife was Princess Izabella Bourbon of Parma, with whom he had two daughters, but both daughters died in childhood. His wife was taken by the smallpox in 1763. He married his second wife, Princess Mária Jozefa of Bavaria, in 1765. However, smallpox also killed him. He had no children from his second wife. József lost his father, Ferenc of Lotharingiai, in 1765, and he was installed as co-emperor in the same year. The emperor, who became more and more insensitive to his private life, his emotional fluctuations, and the beauties of life, became more and more withdrawn. He was interested in nothing but the cause of the empire.

He wanted to be useful, but he also expected this usefulness from his subjects.

Because the machine - the state - only works well if everyone is in place and doing their job. II. József did not want to achieve this in parliaments, not by feudal exploitation of the people, not by discussions of the nobles of the court. He believed that his mother and Frederick the Great's enlightened absolutist thinking gave him enough ammunition to rule his empire quickly and efficiently. He considered the application of pedagogy, the training of educated people, and schooling to be the main means for this. Mária Terézia's educational decree of 1777 helped a lot The matter of education II. József has already raised it to the level of politics. However, he had to face the contradictions of the desired present and future, as well as the centuries-old past. It is true that it would have been beneficial for village children to go to school regularly, but the majority of peasant families could not give up - neither in winter nor in summer - the work of small children around the house either.

II. The reign of József (1780-1790).

The son of Ferenc of Lorraine and Maria Theresa came to the throne prepared, but as he himself said, too late. It is true that he continued his mother's four-decade policy, but he did not have another four decades to mature and implement the countless plans that he had not had the opportunity to do so far. It's enough to just look at the numbers. During the ten years he was on the throne, he issued more than six thousand (6,200) decrees. He almost poured out new and new expectations of a ruler, which often remained only at the level of ideas. (Not counting Sundays, two decrees were published every day.) There was no court apparatus that could cope with this enormous task. We often deal briefly with II. József's relationship with the Hungarians by the fact that he did not crown himself because he despised the Hungarians to such a great extent. (Let us immediately add that it can be said of almost all of the Habsburg rulers that they did not do much good for Hungary and the Hungarian people.) József, who ascended the throne on November 29, 1780, abdicated due to the already mentioned lack of time, and mainly due to the continuous resistance of the Hungarian nobility. about coronation and swearing. The catchy name The Hatted King spread after the poet Pál Ányos's pamphlet on poetry. The poet, who died at the age of 27, died in World War II. He was a prominent figure of noble resistance against József.

A significant part of the Hungarian nobility rightfully protested II.

Against József's person and politics. After all, during the emperor's reign, he never once convened a parliament in Bratislava. In this way, he was freed from any constraints that would have been unavoidable during negotiations with the Hungarian regimes. That was the only way II knew. József to implement his own ideas. Some of the decrees were useful, reasonable, and announced the inevitable changes of the Enlightenment. Another part spoke against its feasibility and violated the elementary interests of nobles and serfs. And a third part served the interests of the Empire (Emperor Joseph), but deeply humiliated and destroyed primarily Hungarian traditions and customs. (Numerous decrees also harmed the interests of other nationalities. József primarily incited the Balkan peoples of the empire against the Hungarians. A good example of this is the anti-Hungarian uprising of the Romanian peasants in 1784, which was partly controlled from Vienna.)

The age in which II. József lived

In the course of history, it has been repeated many times and in many places on Earth, and it can still be seen in the act, that some rulers or ruling groups exercised their power in the name of the people, but against the people. However, let's stick to the history of Europe, the world of the continent's two thousand-year-old culture, religion, social organization, customs, and architecture. Why does this topic deserve to be mentioned when discussing the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century? Without going into detail about the major historical turning points that "arrive" every hundred years, it is worth recalling that the French Revolution of 1789, which then erupted into a Jacobin frenzy, changed the structure of Europe until then. Then a Napoleon comes and the war rages from Paris to Moscow, which is ended by the Holy Alliance in 1815, at Waterloo near Brussels. Another hundred years pass, and in Europe, from Paris to St. Petersburg, the Great War claims the lives of millions, redraws national borders, which in 1918 comes to a standstill for a while. The "isms" that have been straining against each other for a hundred years are reshaping the world view of people living at the beginning of the 20th century. The most dangerous and viable are communism and national socialism, which are ruled by hatred and blood revenge. The world experienced this blood revenge in the years of the Second World War and in the following decades. Another hundred years have passed, and the isms are taking their victims again, in an even more elaborate way, with even greater fervor, now from Brussels to Moscow. They do all this, as before in all cases, in the name of democracy. And our beloved Europe is perishing in this great democracy.

It is true that II.

József was not worthy of his brother-in-law, XVI. The beheading of King Louis of France and his sister, the Queen of France, Marie Antoinette. It was not worth the inhuman bloodbath that took place in the Vendée region of France, which the Jacobins organized against their compatriots. It was not worth the devastating civil war that raged on the soil of France. However, he had already lived through his antecedents, since - although he never denied his faith - he signaled action against the Roman Catholic Church when he opposed the Pope or abolished religious orders. His successors, II. Lipót and Ferenc I had already learned from the French example, which will be discussed later. It could not happen in the Habsburg Empire that nobles and minors, townspeople and farmers, priests and workers were executed en masse just for the sake of ideology. (These bloodbaths have been ingrained in the souls of the European peoples to this day. This may be why the dictatorial left-wing and right-wing forces could always come to power only through a coup d'état.)

For the sake of completeness, let's also go back on the highway of European history. After all, the saying that history is the teacher of life is not unfounded. Let's add, it should be! II. One hundred years before József, in the 17th century, the expulsion of the Turks was the biggest turning point in Europe. The 16th century begins with the spread of the Reformation, then continues with the bloody religious wars. At the beginning of the 15th century, the action of János Husz started a self-destructive process in Europe, the Hussite Wars. There have always been wars that took place for land, power, and the acquisition of each other's goods. However, from the beginning of the 15th century, the attacks repeated every hundred years were launched against the Vatican and against Christianity. This process can be experienced in an increasingly intense form by the beginning of the 21st century. There are hundreds of religions and churches on Earth, but among them, the most furious attacks concern Christianity.

The Josephinist decrees

The first and one of the most important was the forbearance decree issued in 1781. József, like all Habsburgs and the majority of Austrian subjects, followed the Roman Catholic religion. The lords of Vienna were far from agreeing with the persecuting views of the French Revolution. II. However, in addition to Christians, József also recognized and supported the rights of Christians (Evangelicals, Reformers, Unitarians), the Orthodox Church, and even Jews. For example, when he settled the situation of 83,000 Jews in Hungary, it already had a price. Among other things, Jews had to take a German surname. The creators of the decree referred to the fact that their records are easier and more beneficial for them. The Jews were also given the right to manage the affairs of the city offices, which in turn provoked the resistance of the old bourgeois intelligentsia. In the following year, the emperor dissolved the monastic orders that, in his opinion, did not do useful work. Educational, industrial, agricultural and nursing activities were classified among these. However, when the emperor announced the dissolution of the Pauline order and the confiscation of their possessions in 1786, it became clear that, in addition to religious intolerance, anti-Hungarianism also played a role in his decisions, since the banning of the only Hungarian-founded order also targeted national sensibilities.

II.

József made the publication of papal bulls in Hungary subject to royal permission. Another plan was to bring the training of priests into state hands, citing the fact that educated priests would preach the word from the pulpit. Furthermore, he curtailed the apostolic power acquired by Saint Stephen, which was the privilege of the Kingdom of Hungary. At the same time, he limited the number of church holidays. In addition to the already mentioned prohibition of coffin burials, he regulated the burning of candles in churches, also referring to savings. In this difficult period of attacks against Christianity, VI. Pius (1775-1799) could not block it. The French Revolution, which killed priests, and II, which destroyed the power of the church. József (we are still before Napoleon came to power) encouraged the Pope to visit Vienna in 1782. With the "inverted Canossa walk" VI. Pius wanted to achieve that II. Joseph withdraws his decrees concerning the Roman Church. However, the papal trip to Vienna was unsuccessful. The hatted king did not budge from his enlightened views. His ultimate goal was the creation of the state church, which Napoleon would later implement in imperial France.

The king in the hat was not only characterized by his behavior against the church. The national history of the peoples of his empire, especially the Hungarians, left him cold, but he did not respect the ancient traditions either. He based all his actions on the mistaken belief that nobles and peasants, citizens and intellectuals agreed with his ideas, since they were reasonable and served the interests of the empire.

II.

József tried to abolish the county system founded by Szent István when he divided the country into ten districts in 1785. From the flood of decrees, we must highlight the territorial division decree that came into force in 1783. II. József's perhaps well-intentioned, enlightened measures included quite a few that shook the foundations of eight centuries of Hungarian history, culture, and legal system, and did not count on the legitimate resistance of the Hungarian nobility and the majority of the population. The biggest mistake II. József committed it against the Hungarians by disregarding the country's centuries-old history, the strength and faith inherent in the eras built on each other since Árpád. It might have been possible to do this with the always flexible Czechs, the less flexible but winnable Croats and other peoples of the empire, but not with the Hungarians. the stages of this reckless policy was when he transformed the state organization in 1782. With a decree, he united the Council of Governors and the Hungarian Chamber, adding the Hungarian and Transylvanian Chancelleries. Viewed from Vienna, this may have seemed rational, but certainly centralized, but it deeply harmed the interests of the Hungarian aristocracy and the official system.

It was part of the politics of grievance when József took the Holy Crown from Bratislava to Vienna on April 13, 1784, to the imperial treasury, where it was placed as a museum object. Indicating that József does not wish to crown himself. No Habsburg king before or since dared to do this. (For the sake of completeness, it should be added that this fate also awaited the crowns of the other partner countries.)

The king in the hat carried out a similar mutilation of the nation when he issued the language decree, when he regulated book publishing and took many other measures that hindered Hungarian development.

It was a sure sign of centralization when German became the official language of the empire instead of Latin. Among other things, he ordered that a census be held in Hungary between 1784 and 1787. This upset the population, because they saw it as an increase in taxes and a danger of central control. They were not mistaken, because they ordered recruitment, land surveying, and the establishment of offices in Vienna based on this. The census was helped by placing serial numbers on the houses. This was considered a harmless thing, but like all unprepared, quick measures, it also caused people's mistrust.

The Romanian peasant uprising led by Horea, Closca and Crisan, incited by Vienna, was of greater significance and caused far-reaching historical events. This provided an excellent excuse for József to issue the Serf Ordinance, which was implemented in 1785. He wanted to improve the situation of the serfs, which included allowing them to move freely, helping young couples to get married, and to learn various trades. The state also supported the peasants by covering the costs of lawsuits against their masters. In 1787, in the spirit of enlightenment, the death penalty was abolished, and even the name serf was banned. The Viennese idea of levying a uniform tax on peasants and nobles based on the size of the land area made the Hungarian nobility even more vulnerable to II. He tuned it against József. The III. The Swabian resettlement program started by Károly and then becoming massive during the reign of Maria Theresa was also continued by Emperor Joseph. During his reign, about thirty thousand Swabian peasants received significant concessions on land in Hungary, primarily in the Bánát.

The Hungarians did not dare to take up arms against the bloody Romanian uprising for a long time, fearing the reprisals of the Habsburgs, who incited it and supported the Romanian peasants. In the end, the Transylvanian nobility united against the looting and senselessly murdering Romanians and put down the rebellion. At the request of Vienna, only the three peasant leaders of the insurgents were executed, whom the Romanians still consider among their national heroes.

The Josephinist foreign policy

Considering that II.

József looked at everything through the lens of the imperial domestic policy, and his foreign policy also turned out to be disastrous. It should have been a warning sign that one of the richest provinces, Lowland, broke away from Vienna. After that, the Habsburg emperor with one of the greatest rulers of the era, II. Catherine entered into an alliance with the Russian Tsarina. One of the reasons for this was the idea of opening to the east, and the other reason could have been that the enlightened but conservative Catholic II rejected the antecedents of the French Revolution. Joseph. In addition, Austria drifted into the Russo-Turkish war that broke out in 1787, the burden of which was borne by the Hungarian nobility. The battles against the Ottoman Empire caused heavy blood loss and economic damage, which increased the antipathy of the Hungarian aristocracy towards Vienna. The domestic political situation became so bitter that the Hungarians already negotiated with Prussia, because they wanted to exchange Vienna's oppressive policy for Berlin's alliance. The situation of József, who was at the front, was aggravated by the fact that he fell ill and had to travel home to Vienna. The lung trouble that attacked his body did not go away, after a year of suffering it caused his death.

The famous pen stroke

The cited subheading is jr. It became known in Hungarian historiography after the title of János Barta's book on the subject. The king, dying in his sickbed in Vienna, felt his hopeless situation, and in order to save what could be saved, on January 28, 1790, he revoked almost all his decrees. One of his biggest mistakes, which the Hungarians could not forgive him for, was taking the Holy Crown to Vienna and disrespecting the coronation. It can be considered of symbolic importance that the Holy Crown arrived in Buda on February 20, 1790 in a triumphal procession. On the day when Emperor Joseph passed away.

Hundreds of ordinances fell victim to the impatient politics of Józef. Only the decrees concerning toleration, serfs and the lower priesthood remained in force, the others were repealed. The decision was made by the emperor himself, when he signed the document on the revocation of the decrees with his own hand.

II. The reign of Lipot

The hatted king was succeeded on the throne by his younger brother Lipó. Crowned in 1438, Albert I (1438-1439) was the first Habsburg ruler to ascend the Hungarian throne. From 1438 to 1918, IV. Until the end of Károly's throne (1916-1918) - for 480 years - with more or less interruptions, twenty-three Habsburg and Habsburg-Lorraine kings shaped Hungarian history. Little good and more bad can be said about them, since for nearly half a millennium they were decisive for the abolition of the independent Kingdom of Hungary. The few good things are II. He gave Lipót (1790-1792) as a gift to the Hungarian people, who unfortunately only had two years to make his policy a success.

He was a capable, hardworking young man. Thanks to his excellent tutors, who were also well-prepared in the fields of natural sciences and humanities, he was already proficient in many fields of legal, natural science and humanities education before the age of twenty, and he spoke five languages. He inherited many traits from his father, which manifested itself in his melancholic demeanor, among other things. Mária Terézia objected to his neglected dress, his cordial relationship with lower-ranking people, and that he did not pay much attention to his style, neither in his behavior nor, for example, in his writing. A significant turning point in his life was when he married his Spanish bride in Innsbruck in 1765. Two weeks later, his father, Emperor Francis, died, which was also tragic for him, because he was perhaps the most attached to him, and his death was sudden and unexpected. Lipót then ascended the throne in Tuscany as part of the inheritance.

Lipót traveled with his wife to Florence, where a celebratory crowd awaited the new ruler. The first conflict arose with his brother, Prince József, who demanded the Tuscan money due to him from his father's inheritance. The differences between the two brothers remained until the end of their lives. Prince Lipót, who followed the enlightened views, turned Tuscany into a prosperous model state with his popularity, his actions, and the improved lifestyle of his subjects. The reform society, whose members were selected by Lipót, helped him manage state affairs. In the first place, taxation, the reorganization of land leases, and the development of the cultivation of land holdings won the approval of the residents of the already developed Italian state. However, some of those involved did not like the abolition of the military in Tuscany, the reform of the police and public health. Mária Terézia sent Lipót to Vienna in 1778, during the war with the Bavarians. The Grand Duke did not like the trip, but in the end he turned it to his own advantage. He could see into József's dictatorial methods and the disadvantages of centralist politics, as much as Mária Terézia allowed him to. For Lipót, this Josephian policy was abhorrent, and this contributed to a great extent to the fact that when he ascended the Hungarian throne twelve years later, he tried to avoid and change precisely this Josephine policy. József's arrogance and dislike of his younger brother led to the fact that he did not allow the "Tuscan Constitution" drawn up by Lipót - which would have benefited the people of Florence and Tuscany - to enter into force. However, Lipót annulled József's rule in 1790, after the emperor's death. The fraternal, worldview, power tug of war is the explanation for why Lipót can be considered the rare exception among the many Hungarian-hating Habsburgs.

II. The reign of Lipót (1790-1792).

The Roman Catholic religion played an important role in almost every country in Europe, but secular and ecclesiastical dignities manifested themselves with different political and economic backgrounds. Already in Florence, Lipót experienced that Reform Catholicism could not prevail even in the developed Italian province. This experience - because Lipó tried to learn from everything - led him to the decision that when he ascended the throne after József, he refrained from going against the pope as his brother had done.

In Vienna and Bratislava he found himself in a much more difficult situation than he experienced in Florence. The destructive effect of Joseph's reforms almost buried the empire under itself. The foreign policy situation in particular caused a headache for the monarch who ascended the throne and for the administrative machinery of the Court. The war against the Turks was still going on, and the Hungarian, Polish and Czech nobility were dissatisfied. Prussia's opposition to Vienna was even supplemented by the fact that Berlin supported the secession of the Low Countries from Austria. By pursuing a peaceful policy, Lipót succeeded in preventing the uprising of the Hungarians, the Prussians, and the Belgians. He constantly involved his son, Ferenc, in his plans, who will succeed him on the throne.

The ruler's wisdom, also called Lipót the Wise by his subjects, was spectacularly manifested when he crowned himself in Frankfurt (October 9, 1790), Bratislava (November 15, 1790), and Prague (September 6, 1791). During the years of his reign, the French Revolution unfolded, which he welcomed at first, but towards the end of his reign, at the beginning of 1792, he already saw its dangers. This French Revolution was no longer about enlightenment, about ensuring a better life for people, but about a dictatorship that had lost control. In order to protect Austria, Leopold even entered into an alliance with the Prussians to prevent the "revolution" from spreading across the border.

Lipót's politics is characterized by the fact that several laws dealt with criminal law during his reign, including the abolition of torture and the death penalty. The laws dealt with the regulation of the destruction of forests, the cessation of gambling, the exploitation of mines, and the conditions of acquiring wealth.

His short reign of almost two years ended unexpectedly and suddenly. Many people thought that Lipót, who died at the age of 44 after a two-day illness - rumors, whispers, a masonic conspiracy, French hostility, suicide - did not die a natural death. The official report is of death due to pleurisy. Kings who died suddenly, unexpectedly, under suspicious circumstances are common in Hungarian history, one might say they were common. However, this was not typical of the history of the Habsburg rulers, as they were "protected".

II. Lipótra's motto was perhaps really apt, which read: "The treasures of kings are the hearts of their subjects." Presumably, this also contributed to the fact that the Court made peace with the Hungarian nobility, and intellectual products were born in Hungary that could not have appeared before this. The works of János Batsányi and Ferenc Kazinczy are among the figures of the Hungarian Enlightenment.

Author: historian Ferenc Bánhegyi

(Header image: Wikipedia)

The parts of the series published so far can be read here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28., 29/1.,29/2., 30., 31., 32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46., 47., 48., 49., 50., 51., 52., 53., 54., 55.