"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated.

Ascension of Maria Theresa to the throne

It was already mentioned in the previous chapter that III., who ascended the throne in 1711, King Charles of Hungary (German-Roman Emperor under the name Charles VI) had no son. However, the House of Habsburg could not lose its ruling power over Austria and its neighboring countries since the 13th century, so they looked for a solution. This is how court lawyers came up with the use of "legal order, sanctification", "practical arrangement", Pragmatica Sanctió in Latin. An example of this was also found after researching historical events many centuries ago. The basis is the (Habsburg) family agreement adopted in 1703, which concerned the order of inheritance. In 1713, nothing else happened than that this order of inheritance was extended to the female branch as well. It was forced and twisted, but female inheritance was enshrined in law. The Transylvanian and Hungarian orders adopted it in 1722, which was officially announced on April 19, 1723. (Princess Mária Theresia Walpurna Amália Krisztina was six years old at the time.) III. In this legislation, Károly declared that the Habsburg Empire was indivisible. Bavaria, France and Prussia did not accept the order. In 1740, the latter started an eight-year war against Austria, which took place for the control of the rich Silesia, and which went down in history under the name of the War of the Austrian Succession. Silesia remained the property of Prussia. Vienna, on the other hand, preserved its unity. Thanks to the Hungarians (after what happened at the 1741 Bratislava Parliament), relatively peaceful construction work began in the Habsburg Empire.

Maria Theresa was the only female ruler of the Habsburg Empire. Through her husband, Emperor Ferenc of Lorraine (1708-1765), she entered the pages of history as the founder of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. The French-born Ferenc of Lotharingia – whose family, as a result of the conflict with the Bourbons – fled to the court of the arch-enemy Habsburgs, to Vienna. Here, over time, he entered into a confidential relationship with the young princess, Mária Theresia. Love developed between the two young people, which was sealed with marriage in 1736. It was a love marriage, which rarely happened in the history of the Habsburgs.

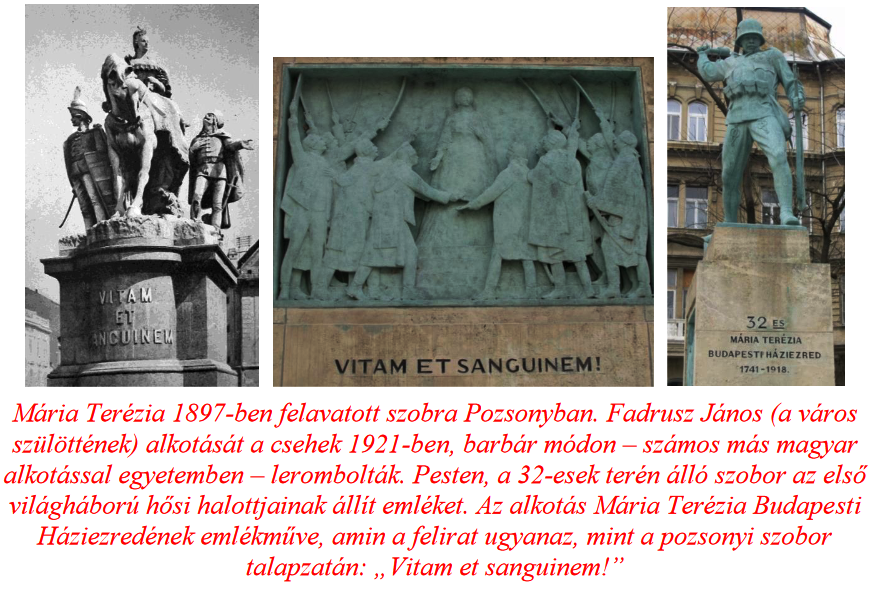

The Hungarian nobility helped the queen in her plight at the 1741 parliament, when they offered their lives and blood to save the empire. There it was said: "Vitam et sanguinem pro rege nostro!" (Our life and blood for our king!)

Consolidation of Maria Theresa's reign

The young princess could participate in the meetings of the imperial council from the age of fourteen, but her father, III. At that time, Károly did not think that his daughter would be his successor. He hoped that a son would also be born. He was not prepared to rule, but he was thoroughly prepared in the fields of natural sciences, musical, historical and literary education, and knowledge of languages. In 1740, the empress inherited a serious situation from her father, as she came face-to-face with II. With King Frederick (1740-1786) of Prussia, who attacked the Habsburg Empire without a declaration of war. The queen was unlucky, because the excellent strategist, educated, broad-minded politician, and ambitious ruler Frigyes, who ascended the throne the same year as her, created the Prussia that later served as the basis of German military power, a new European superpower. In the aforementioned war of succession, in addition to Silesia, Vienna also lost a significant part of the Balkans. Mária Terézia knew that she could only keep her power and throne with the help of the Hungarians. This is how the memorable Bratislava Parliament of 1741 took place. In exchange for the loyalty of the Hungarian nobles, the queen repealed III. Some of Károly's anti-Hungarian measures. Paying particular attention to the sensitive point of the Hungarian nobility, the tax exemption, the donation of land holdings, as well as the command of the Hungarian army in Hungarian, as well as the respect of their ancient symbols.

Nearly half of the empress's four-decade reign was filled with wars, which depleted the economic power of the empire. He launched most of the military enterprises, often out of compulsion, against the Prussians, of which the Seven Years' War between 1756-1763 stands out. One notable episode of this was the enterprise of the Hungarian hussar regiment led by András Hadik in the fall of 1757. Hadik broke into Berlin at the head of 4,300 hussars and foot soldiers. "The sacking of Berlin" was the most humiliating event of Frigyes Nagy's long military career, which caused a great echo throughout Europe.

(The Hungarian film Hadik, which was released in 2023 and was produced at considerable expense, very faithfully presents the Hungarian

hussar feat approved by Mária Terézia. Many of us remember the work from this money, despite the fact that the film is also a worthy memory of the Hungarian hussars asserts, it places the emphasis on the positive role of Mária Theresia. With this money, it would have been possible to choose from dozens of Hungarian historical events that have not been processed in the language of the film, rather than presenting the age of Mária Theresia.)

However, in connection with the two prominent war events, we saw that the glory and power of perhaps the most significant ruler of the Habsburg Empire

was owed to the Hungarians. What Hungary received in return from the "good empress" is also mentioned below.

"We have to feed the sheep if we want to shear and milk them"

This is what Mária Terézia originally said - perhaps it was never uttered - but it was often quoted as saying that she instructed the economic and political machinery of the Court to force the Hungarians to work and serve not only through oppression and violence, but also sometimes with concessions. The queen was the one who not only recognized what gives the Hungarians strength and faith, but also took many effective steps to break the Hungarians precisely because of this realization. In the 18th century, the Scythian origin of the Hungarians and their kinship with the Huns and Avars was not yet a topic of debate. This was well known not only in Hungary, but also in the countries to the west of us, especially the ruling classes. It is a well-known proposition that was practiced long before, in ancient times and in other areas of the world, that "Take the history of the people, and then you can do what you want with the people!" Mária Terézia then used this strategy effectively against the Hungarians.

Mária Theresia was continued by her father, III.

Mária Theresia was continued by her father, III.

The only obstacle to Károly's unifying policy was the resistance of the Hungarians. There was no problem with the always flexible Czechs, who were "more Austrian than the Austrians". Apart from the Battle of Fehérhegy (1618-1620) at the beginning of the 17th century, when the Czech orders resisted the Habsburg dynasty, they never confronted Vienna again. Then they suffered a crushing defeat in this little war as well. It is true that the Thirty Years' War was started, but the burden of it was already felt by the whole of Europe. The last national hero of the Czechs was János Husz at the beginning of the 15th century. The followers of János Husz, who died at the stake in Konstanz in 1414, sparked the decades-long Hussite war, the burden of which was then borne by half of Europe. The Czechs activated themselves once again in the 20th century, when the Czech politicians Benes and Masaryk destroyed the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy with powerful Western - French and Anglo-Saxon - help and took a significant role in establishing the Trianon peace decree. (In their typical way, they "thanked" Vienna for centuries of protection.) The other member states of the empire: Silesia, the areas beyond Lajta, Croatia, Slavonia, the Military Border Guard Region on the Adriatic coast, Banát and other smaller and larger parts of the empire conformed to Vienna as it was precisely the interests of the Habsburgs that required it.

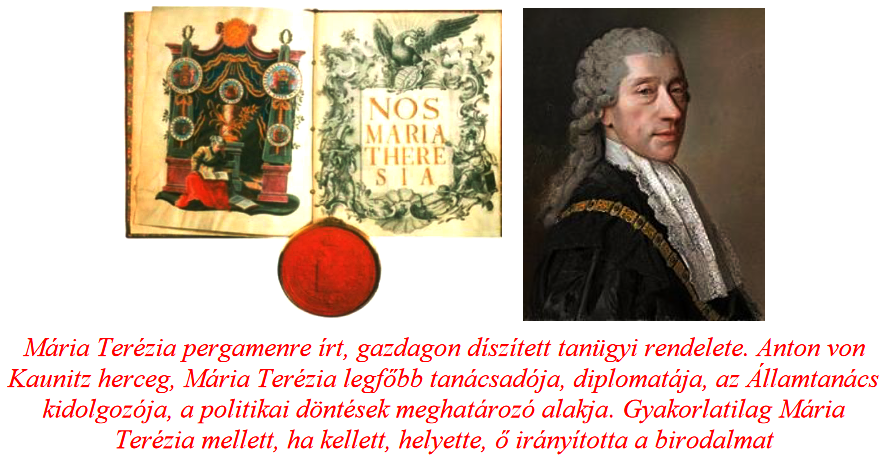

During her four-decade reign, Maria Theresa issued numerous decrees. One of the most famous of them is the double customs decree issued in 1754. Its essence was that a high export duty was imposed on Hungarian agricultural products, which, however, did not apply to the Austrian and Czech territories. On the other hand, Austrian and Czech industrial goods went to the internal countries of the empire, including Hungary, at low prices. (High customs duties already had to be paid on Prussian or French industrial products.) It is worth noting that Mária Theresia continued what her father had started. But she could not inherit the German-Roman imperial crown because of her female nature. Thus, her husband, Ferenc I, became the emperor nominally, but the Habsburg empress did not let the actual control out of her hands.

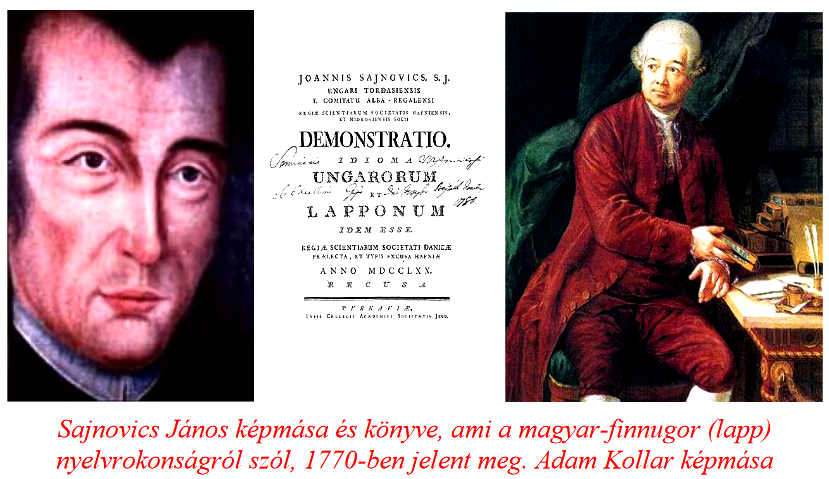

Mária Terézia knew very well how to keep alive the historical faith of the Hungarian nobility and their respect for their ancestors with one gesture at a time. Such was the case with the inauguration of the Order of Saint Stephen and the bringing home of Saint Jobb from Ragusa. The latter was preceded by years of negotiations, as a result of which the Republic of Ragusa was willing to extradite Szent Jobb to Hungary. True, in the meantime, in January 1764, the massacre in Madefalv decimated the Székelys took place, as well as the appointment of Adam Kollar, a literate Hungarian-hating Tót, as Vienna's chief archivist. In 1765, Transylvania was appointed as the Grand Duchy, which placed the centuries-old integral part of Hungary under the authority of Vienna.

Among the legislations and decrees, the survey of the territory and lands of the country, and indeed of the entire empire, should also be mentioned. The great work began in 1764, which then lasted for twenty-one years, and II. It was completed in 1785 during the reign of József. The land survey served a dual purpose. On the one hand, the accounting of property relations, and on the other hand, the planning of the march of the army and its military enterprises.

Both for this and to increase tax revenues, and at the same time to keep the burdens of the serfs at a similar level, the unified urbarium was introduced within the countries of the empire in 1767. The rent decree did not reduce the amount of tax payable to the treasury. However, it reduced the burdens of the serfs to such an extent that the landlord could not demand a higher tax burden based on "customary law". After that, the serf who owned the entire land could only be obliged to work 52 days a year (one day a week) and 104 days on foot (hand labor). In addition to these, the land serf also paid a smoke tax of HUF 1 per year, and the rate of the ninth and tenth was also regulated. One of the drafters of the decree was a confidant of Mária Terézia of the Hungarian lord, Pál Festetics.

The inclusion of the portion and boiling point in the regulation was less popular.

The portion affected the villages in the path of the army's retreat in case of military exercises or war. The soldiers had to be accommodated and provided with food. This practically made life difficult for the serfs of hundreds of villages, and even ruined it during the Habsburg rule. And the forspoint meant that the serf had to transport the soldiers to the specified place on his own cart with his own draft animals. This was also a significant burden for them. It should be known about the Austrian war machine that mercenary armies were previously recruited in case of war. However, this was slowly replaced by the establishment of a permanent army stationed in barracks. In 1745, the empress founded the Terezianum, which enabled secondary academic training for young nobles. It should not be confused with the Hungarian noble bodyguard established fifteen years later (in 1760), in which only Hungarian boys blessed with certain physical and mental abilities could enter. Among the members of the bodyguard operating until 1848, we should mention György Bessenyei, József Gvadányi, András Dugonics, Lőrinc Orczy, and Ádám Pálóczi Horváth, the bodyguard writers who laid the foundations of modern Hungarian literature.

The Queen's educational, cultural and health reforms

The radical transformation of Hungarian education and culture took place in 1777, when the Decree entitled Ratio Educationis, or System of Education in Hungarian, was published. Prior to this, in the fall of 1770, the general health regulations, Regulamentum Sanitatis, issued by the Council of Governors were published. This stated that every county and city must employ a doctor with a degree, and every district must employ at least one midwife (qualified midwife). Orphanages were set up to accommodate the children who were left alone. In these, learning was made mandatory, and upon leaving the orphanage, the young man had to know and practice at least one profession. And the helpless poor people were placed in poorhouses.

The Ratio Educationis was the first regulation in the Hungarian education system in which the spirit of the Enlightenment played a role. In addition to religious elements, scientific knowledge also appeared in the curriculum. The latter mainly encompassed agricultural and other natural science subjects, the distinguished purpose of which was to strengthen the economic life of the empire. The decree states that all children aged 7-13 must attend school. True, this remained only a wish, it was only partially realized in practice. They also ordered that children in all countries of the empire study from textbooks with the same content, which particularly adversely affected Hungarian students. (We will touch on this in relation to the rewriting of Hungarian history.)

After the end of Turkish rule, the University of Nagyszombat was declared a royal university by Mária Terézia in the summer of 1769, and in 1777 its operations were moved from Nagyszombat to Buda. The measures affecting the university also meant that the institution was placed under state control. Vienna could do this because the Jesuit order was dissolved in 1773. (In addition to medical education, as well as theological and legal subjects, the faculties of agriculture and natural sciences also appeared. An observatory and a library were created, and all of this also bore the hallmarks of the Baroque style.) It should be noted that in April 1770 the mining officer training school in Selmecbánya was upgraded to academic rank. was built, which can be considered the predecessor of the University of Sopron.

Among Maria Theresia's decrees, let's mention the one dated April 23, 1779.

This was about the fact that the queen had annexed the city of Fiume to Hungary as a "separate territory". (The name of the city has been Rijeka since 1947.)

The rewriting and falsification of Hungarian history

We have already mentioned Mária Terézia's multifaceted activities related to Hungary. Among them, many intellectual, material and especially architectural monuments can be listed, which show the figure of the developer, the benevolent queen. However, we must point out that from 1765 until the end of his life, he ruled the empire, including Hungary, with enlightened absolutist monarchical methods. During this period, Mária Theresa did not even convene a parliament, which already indicates the duplicity of the kind empress. (His son, the "hatted king" who followed him, did not even hide his open dislike and hatred for the Hungarians. More on this period of rule will be discussed in the next section.)

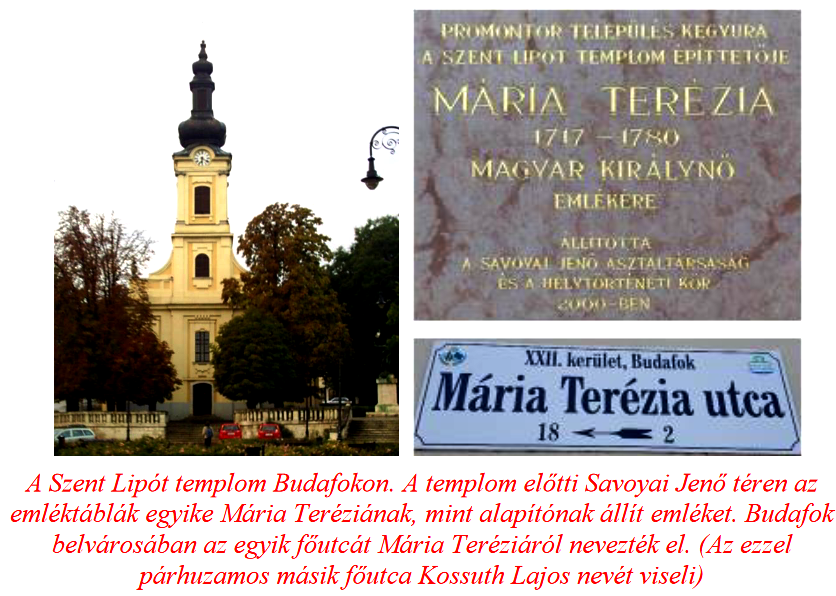

Dozens of Roman Catholic churches were built in the second half of the 18th century, and the people of the affected towns and villages still remember the founder Maria Theresa with respect. As an example of the Baroque churches, let us mention the St. Lipót parish church in Budafok, which was consecrated in the autumn of 1755 by the bishop of Veszprém, Márton Bíró Padányi. The Budafoki church was also consecrated in honor of the patron saints of the Promontory, St. Sebestyén and St. Vendel. Mária Terézia donated the red marble altar and the altarpiece depicting Saint Lipót to the church in Budafoki. The cult of the queen was founded by the founder of Budafok (Promontórium), the victorious general, Jenő Savoyai.

In addition to church construction, however, the court machinery painstakingly ensured that no printing press could operate unchecked anywhere in Hungary. Thus, the nobles, always sensitive to their national pride, could not give a meaningful answer to the unjust accusations and slanders that Vienna threw at our country after the defeat of the Rákóczi War of Independence. In these years, the unscrupulous falsification of Hungarian history began. The Court appointed a scribe of Slovak origin, Adam Kollár, to head the main archive in Vienna. Kollár did everything - unfortunately with success - to erase documents about Hungarian prehistory, the Middle Ages, the culture and true history of Hungarian history. In their place, fake "documents" were placed on the shelves of libraries and archives. In other words, he methodically falsified Hungarian history. Kollár dared to sink documents about the continuity of Hun-Avar-Hungarian prehistory, the recapture of the country, the economic life, culture, and true history of medieval Hungary. What was published, on the other hand, was full of false claims. The generations who used Kollar's history books could learn that the busy Slavic and German population living in the Carpathian Basin, doing useful work, was oppressed, robbed, and endlessly taxed by the small Hungarian nobility. In these years, Kollar strengthens the Pan-Slavic theory, and in order to achieve his goal, he even classifies the Romanians among the Slavs.

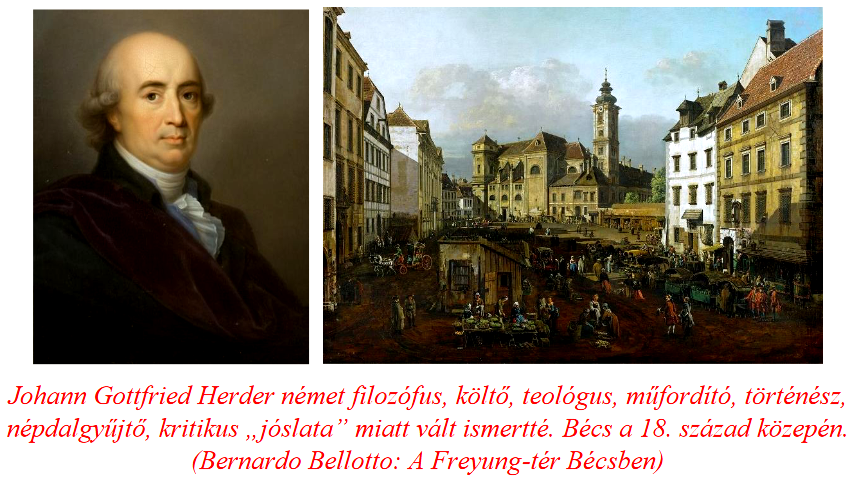

He describes the Hungarians as barbaric herds, whom European cultured peoples will sooner or later cast out from among themselves. At that time, they will be made aware throughout Europe that the Hungarians are a foreign people that will never be able to fit in among the Latin, Germanic, and Slavic peoples. The court clerks and the secret police allowed Kollar and his followers free rein, while the counterarguments and written responses of the Hungarians were banned. Printing presses were under strict state control. One of Kollar's pamphlets, however, whipped up the feelings of the Hungarian nobility to such an extent that, as a result of their fierce protest in the 1764 Parliament, Kollar was removed from office. It is characteristic of Mária Terézia's duplicity that the services of the Hungarian-hater Kollar were secretly used. The fact that the heir to the throne József, the later hatted king, was also influenced by Kollar's spirit is a clear proof of this. The German scientist Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), who became known among Hungarians with his infamous prediction, was brought up under the teachings of the Slavist archivist.

János Sajnovics (1733-1785), a Jesuit monk born in Tordas and of noble origin, was the forerunner of the falsification of the Hungarian language and the history that developed from it. Sajnovics practiced many sciences, but was not originally a linguist. However, he took part in the expedition led by the astronomer and naturalist Miksa Hell, whose members conducted primarily natural science research in the countryside of Northern Norway in 1769. A research group working on behalf of and with the support of Mária Terézia noticed the supposed kinship of the Finno-Ugric and Hungarian languages in Lapland. The "discovery" could have sunk into oblivion. Court politics had the good sense to see in him that the prehistory of the Hungarian cavalry and archers, the Hun-Hungarian kinship, be replaced by the "fish oil-smelling" fraternity. Whether the linguistic kinship is true or not, the point was to break the millennia-old belief of the Hungarians' historical consciousness. It worked.

Today's Habsburgs, our 21st century compatriots who do not think in terms of the nation, still see and value everything differently than those who think in terms of the nation.

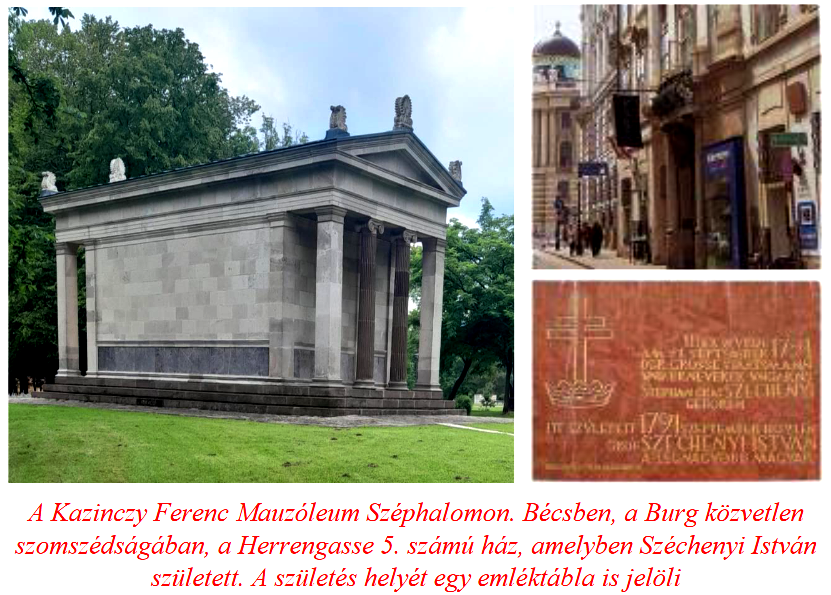

In the otherwise benevolent Herder's work Sturm und Drang, his sentence about the Hungarians, written only as an example, is explained differently than Kazinczy, Kölcsey and their circle did earlier. The sentence goes like this: "the small number of Hungarians wedged between other peoples - Slavs, Germans, Romanians - may not even be able to discover their mother tongue after centuries." However, the famous German scientist did not know that at the same time, in 1791, when he wrote down his prediction, a poet named Mihály Vitéz Csokonai published his essay The Enlivening of the Magyar Language. He could not have known that Ferenc Kazinczy started building the Mansion at Bányácska (Széphalom) at that time, which would later become one of the centers of Hungarian intellectual life. He didn't even know that József Katona, the author of our national tragedy, Bánk bán, was born in this year. And the great German scientist could not have known that István Gróf Széchenyi, the greatest Hungarian, was born on September 21, 1791 in Vienna, next to the Hofburg. He could not have known that in the following decades such giants of writers and poets would enrich Hungarian linguistic and intellectual life as Mihály Vörösmarty, Mór Jókai, Mihály Tompa, János Arany, and Sándor Petőfi. And it never occurred to him that the greatest figures of Hungarian history, such as Ferenc Deák, Lajos Kossuth, Miklós Wesselényi, Lajos Batthyány, the mathematician Bolyaiak, were also born of this age and would be decisive figures in the construction of our society. In the end, Herder's prophecy benefited our nation, because, as so many times in our history, when the Hungarian spirit was harmed, it provoked resistance, "Hungarian virtue" in the good sense.

The generations growing up at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century had only distorted information about the struggling life of their predecessors, the struggle of the orders, and the politics. The political pamphleteering that started in the middle of the 17th century, the peak of which was the writings of Miklós Zrínyi, completely withered after the peace treaty in Szatmár. II. József (1780-1790) the new king's press order issued in 1781 launched another series of attacks against Hungary. Professors such as Lipó Hoffmann were appointed to the University of Pest, among others, who considered Hungarians to be "a race that emerged from the dens of Asia". Already at the time of the "good empress", the view was spread that the Hungarian nobility was characterized by the stench of tobacco, drunkenness, tangled hair, laziness, gaudy clothes, ignorance and savagery. (It's as if we only hear the words of the superiors describing Hungarianness after the "regime change" of 1990, according to which our people can only be recognized by the bő gatya and the peach pálinka.) Count Ferenc Széchényi, who was a supporter of Vienna, wrote that: "Under the ruling house among the nations belonging to it, only Hungarians can be defamed with impunity".

The era in which Mária Theresia also lived was a period of great change in European history.

The conservative customs of the Middle Ages and modern times were still alive, the world view was determined by the Christian religion, but the ideological currents of the "enlightenment" had already appeared. This could have been good, it could have brought about a change in the already ossified ideas that would create a beautiful new world for the benefit of the people, but it did not happen. The marauding, robbing sea powers that covered entire continents in blood and got immeasurably rich from it lost their compass. The English and the Anglo-Saxon powers aspired to world domination. And the French and the peoples of the Low Countries attacked Christianity, on which the world's most beautiful architectural wonders, unparalleled works of art, science, and technology were built. The leaders of some European nations seem to deny their identity, the constructive work of their predecessors, and their activities are based on self-destruction. However, the roots of this phenomenon, which often seems incomprehensible, lie in the discussed age, the 18th and 19th centuries. can be traced back to the turn of the century.

Author: historian Ferenc Bánhegyi

(Header image: Screenshot from the Mária Theresia film series )

The parts published so far can be read here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28., 29/1.,29/2., 30., 31., 32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46., 47., 48., 49., 50., 51., 52., 53., 54.