"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated.

From the fall of neo-absolutism to the 1861 parliament

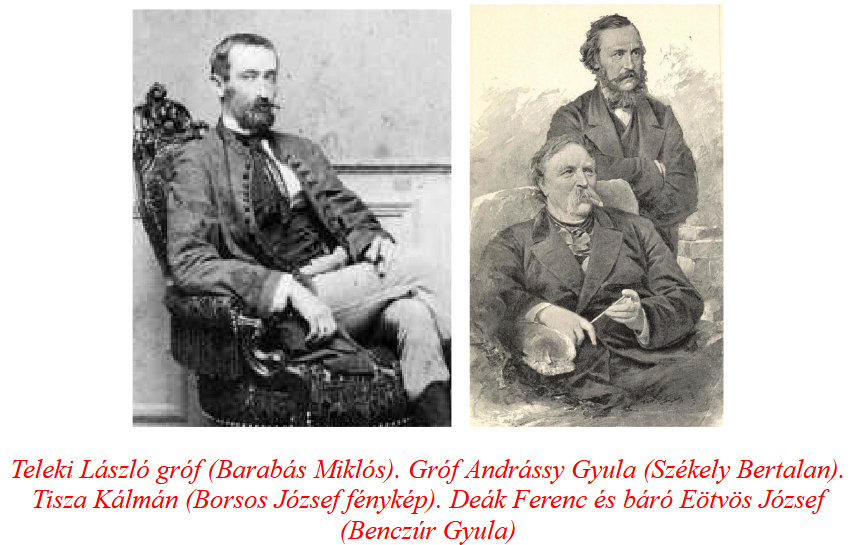

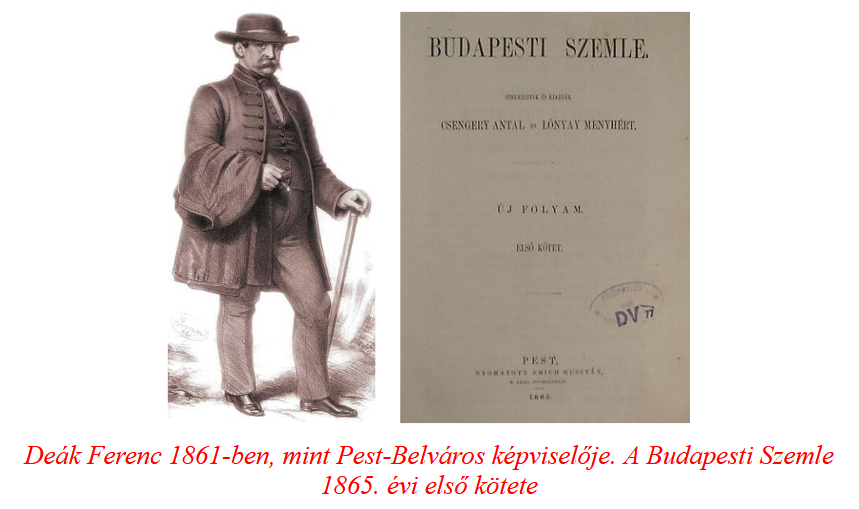

Among the prominent figures of the emigration, Lajos Kossuth was never able to return home, only in 1894, dead. Count László Teleki - who was also sentenced to death in absentia along with several others - returned home to Gyömrő in January 1861 under adventurous circumstances. Gyula Gróf Andrássy, whom Parisian ladies called "beautifully hung", returned home in 1857, which was arranged for him by his influential mother. Tisza Kálmán emigrated abroad for a year and a half in 1849, but was able to return home with impunity. After the Lamberg murder on September 28, 1848, József Báró Eötvös traveled to Vienna, then to Munich, and lived only for his humanistic studies. He returned home in 1853, exclusively engaged in scientific work, but from 1861 he took a serious part in political work again. Ferenc Deák was perhaps the only one who did not emigrate, and he played a decisive role in bringing about the compromise. He could do this despite the fact that he was a member of the Batthyány government.

In the 1860s, many new actors appeared in Hungarian political life. They were not involved in the events of the 1848/1849 War of Independence, either because of their age or because of their worldview. Regardless of this, three main directions of party politics emerged. There were the so-called 47s, there were those who insisted on the laws of April 48. However, more and more of them started from the situation after the fall of the War of Independence in 1849. They thought that it was worth continuing the nation-building work with a clean slate.

The year 1860 can rightly be considered the year of political activation. As Kossuth noted, the next step after the Bach system took place in 1860, on the anniversary of March 15, which was "a celebration of the awakening of the Hungarian national spirit". On this day in Pest, the protesters clashed with the police, which resulted in one fatality. University law student Géza Forinyák suffered such serious injuries that he was left dead on the pavement of the street.

Another tragedy of the year 1860, when Count István Széchenyi died under unclear circumstances in the sanatorium in Döbling (Vienna) on April 8. Széchenyi whipped up the national sentiments of Hungarians with his essays written in his solitude in Döbling, especially his discussion paper entitled Ein Blick (A Glance). As he writes: "Many Hungarians have only now come to true love for their country, and children only show devoted love and respect for their parents when their lives are threatened."

During Kossuth's experiences abroad, he realized again and again that he could not count on help from England, the United States, or France. After the promising French-Hungarian negotiations III. Napoleon's sarcastic letter disillusioned Kossuth and the other members of the emigration: "I am extremely sorry that the liberation of your country must now stop. I can't do it any other way. An impossibility. But please... don't be discouraged, trust me and the future".

The Battle of Solferino in 1859 brought a turning point, in which the allied French and Sardo-Piedmontese troops won a victory over the Austrians. This event in 1860 brought the whole of Italy to a boil. Garibaldi's series of victories started from the southern regions of the country, which led to the creation of Italian unity. In 1861, the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed. This and the establishment of the German Empire under Bismarck in 1871 were more important to the European powers than supporting the cause of Hungarian freedom.

It was not by chance that Kossuth sent a message home to his compatriots: "... a nation can only promise itself a future if, with its determination, rising to the heights of the situation, it does not shy away from the 'wisdom' of a coward who ignores difficulties, but does not shy away from any sacrifice... people forget a lot when a nation has nothing nor can anything be more fatally harmful than forgetfulness—nothing is more important than memory!” (I note, this is at least as true today!)

The Viennese court was not idle either. József Ferenc's imperial-royal decree, the October Diploma, issued on October 20, 1860, dislodged the stagnant political life. Although the October diploma promised constitutional foundations, at the same time it put the prospect of merging Hungary into Austria. He maintained the imperial idea of 1849, so he referred the affairs of our country to the jurisdiction of the Imperial Council. He promised extensive autonomy to the countries and nationalities of the empire. Hungary regained its constitutional rights, as well as the Hungarian Chancellery and the Council of Governors. However, foreign affairs and military affairs would have remained in the hands of Vienna. The language of education became Hungarian. The Hungarian Parliament rejected the decree in 1861, despite all the fine promises of the monarch.

The February Patent issued on February 26, 1861 was another attempt by the court to break Hungarian independence. It was nothing more than an open imperial order, which transformed the Imperial Council established in October into a legislative body with limited powers. This was already issued by the Schmerling government, which had risen in the meantime, which gave only 85 Hungarian, 26 Transylvanian and 9 Croatian-Slavic delegates of the 343 delegates of the imperial council the opportunity to have a say in the affairs of the empire. The ruler still retained unlimited right to manage foreign affairs and military affairs. The Hungarian Parliament of 1861 also rejected this. It should be noted that among the provinces of the empire, the resistance of the Hungarians was the strongest. József Ferenc dissolved the parliament in 1861, among other things due to the suicide of László Teleki.

None of the October Diploma and the February Pátens entered into force, but they were important milestones in the preparation of the agreement.

From the Parliament of 1861 to the publication of the Easter article

In Paris on May 6, 1859, Lajos Kossuth, László Teleki and György Klapka established the Hungarian National Directorate as the leading forum of the government in exile. Teleki wanted to return home secretly, with an English passport. He first traveled to Dresden to see his love, Baroness Augusta Lipthay. The Saxon police had already watched the Hungarian politician here and arrested him. Before Christmas, he was dragged to Austria, where he even had to spend ten days in prison. Ferenc József then assigned him to himself and promised him that he would not participate in any political activity. Teleki returned home to Hungary in January 1861. However, László Teleki enjoyed great popularity among the Hungarians, so he could not escape the political invitation.

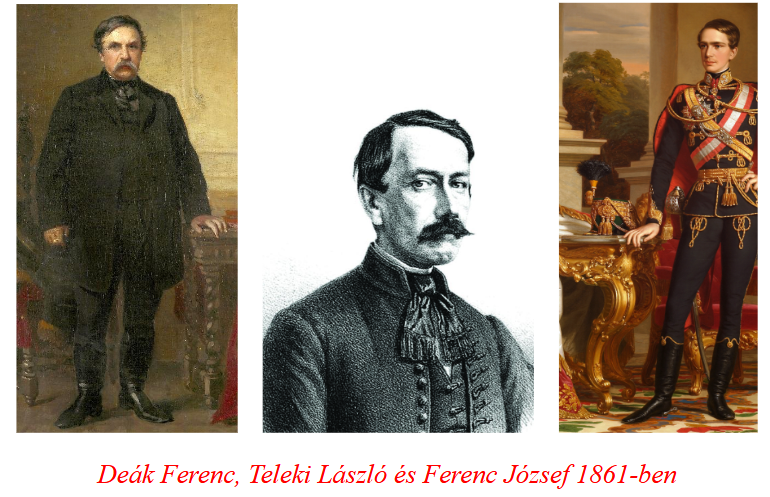

On April 6, 1861, the monarch convened the parliament, at which two parties, fighting a sharp political duel, appeared. More and more people wanted a compromise with Vienna. The nobles and the entire country suffered from the passivity that lasted for almost two decades. One political side was the Felirati Party led by Ferenc Deák, the other was the Decision Party organized and managed by László Teleki. The names of the parties reflected their programs. Deák and his fellow politicians explained why they insisted on the laws of April 1848 in the "inscription" addressed to the monarch. This is where the name of the Felirati Party comes from. Teleki and his supporters considered Laws 48 only as a starting point, and tied the terms of compromise to much greater independence. They "resolutely" stood up for their radical demands, thus gaining many new supporters and a majority on the lower board. Hence the name of the Decision Party. The Telekis stuck to their principles laid down in emigration. László Gróf Telekinek would have had the right to participate in the upper table of the parliament. However, he ran for elections and wanted to take part in a militant lower table. He won the parliamentary election and appeared in Pest as a representative of the Abony electoral district.

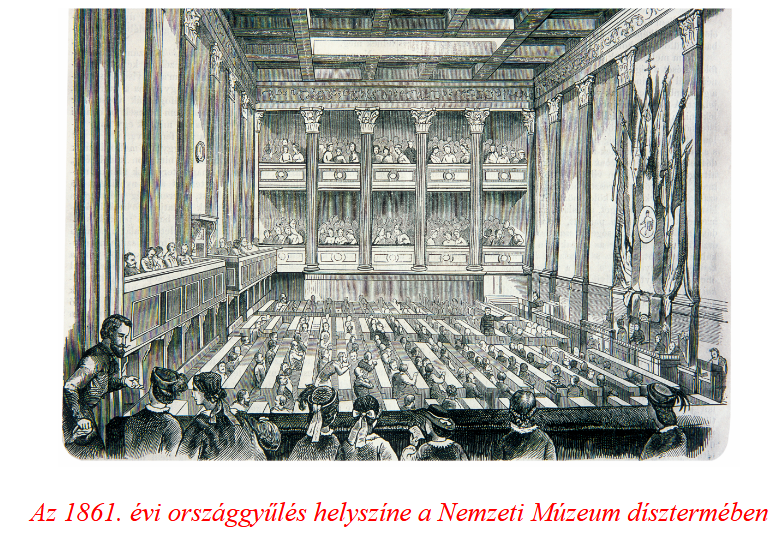

The location of the 1861 Parliament in the hall of the National Museum Among other things, the Decision Party did not recognize the illegal accession of Ferenc József to the throne in 1848. They tried to get the parliament to dissolve itself, so they ruled out any kind of deal. The ambassadors of Transylvania and Croatia were not present, which was also illegal. The debate also escalated within the Decision Party. The majority was inclined to bargain, but Teleki was not, and so he was increasingly left alone. It should be mentioned that on the night of May 8, László Teleki was hosted by his cousin, fellow politician Kálmán Tisza. Unfortunately, we will never know the details of what they talked about for four hours. However, it is a fact that when Tisza left the apartment in Pest, the otherwise sensitive László Teleki committed suicide.

Primarily members of the National Assembly, but also interested people and journalists, who could only enter the Museum Garden with a ticket, were excitedly waiting for the Deák-Teleki debate, which would determine the future of the country, which then could not take place.

It could not happen, because on the morning of May 8, 1861, when the representatives gathered, they learned the tragic news that László Teleki had committed suicide at night. The meeting was adjourned, the representatives were overwhelmed by grief and helplessness. There was great indignation throughout the country. There were places - including in Győr - where demonstrators clashed with the imperial military, which resulted in bloody consequences.

Teleki's death delayed the settlement, but did not prevent it. The manuscripts found in his room, which contained the outline of his planned speech, bear witness to the fact that he did not give up his goal of emigration even at the crucial moment. He clearly rejected every point of the October diploma and the February patent. He firmly stood for the creation of an independent Hungary. (His death, like the death of so many Hungarian patriots who strived for independence, was once again favorable for Vienna. In this case, foreign favoritism did not arise, as, for example, in the case of Miklós Zrínyi or István Széchenyi. Many do not believe this.)

László Teleki, a member of the Kisfaludy Society, published his drama Kegyenc in 1841, which takes place in the years of the fall of ancient Rome, but depicts the Hungarian historical reality during the Reformation. The moral corruption of imperial Rome was the blueprint for Metternich's politics of the time.

The power of money, the formation of banks, the economic situation

Before continuing with historical knowledge rich in events, it is worth mentioning the economic background of the era, if only in outline. This topic is obligatorily omitted from history textbooks - from elementary school to university notes. I say this as someone who has been the author of history textbooks for 25 years. Historical studies and books from the pen of academic authors are shamefully silent about the movement of the financial world outlined below. At the same time, there are more and more economists and historians who can and dare to speak openly about this taboo topic.

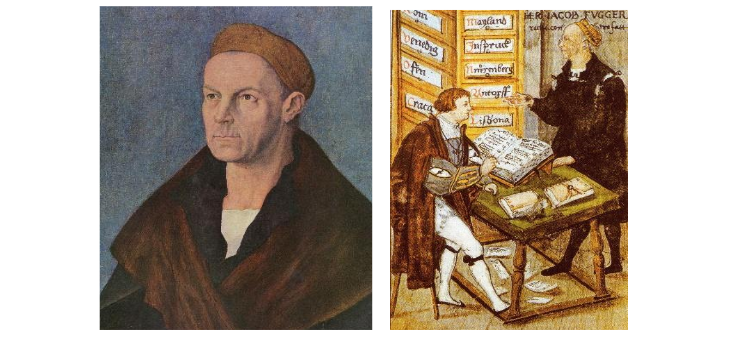

The Fugger family, who dominated a part of the imperial and royal courts in medieval Europe, was discussed earlier during the trial of the Hunya family. Emperor Charles V of Habsburg, the "lord of half the world", took out the biggest loans from them. The emperor then paid back the huge sums borrowed from the Fuggers to the banker family at interest. There was plenty of it, since the plundering of the Spanish colonies brought enormous income to the court. As a result, the emperor's brother, King Ferdinand I of Hungary, also became an employee of the banking family from 1526. It is true that earlier, in 1495, János Thurzó, a lord of the Highlands, concluded a contract with the Fuggers. According to this, the income of the gold, silver and copper mines of Besztercebánya and its surroundings was taken over by the banking family, and they even created a joint business in minting coins. However, another "businessman", Imre Szerencsés (Fortunatus), who fled Spain to Buda, intervened in the business of the Fuggers (as the Hungarians called them, the stingy ones). Szerencsés was accused of fraud, and Fugger party supporters robbed his house in Buda, but he did not give up the fight for the big profit. Sértsésé accused the Fuggers of fraud in the 1960 parliament. The case reached the Pope, who, in alliance with Charles V, threatened the Hungarians, writing a letter to II. To King Louis: "Strongly advocate and demand that justice be served to the Fuggers!" They "delivered justice" to the Fuggers, in exchange for which Hungary received a HUF 50,000 loan, which was almost not enough for anything. The plight of the country was compounded by the fact that Sülejmán Nagy embarked on his conquest campaign against the Kingdom of Hungary just in these days - perhaps not by chance. The mine work of the Habsburgs also contributed to the tragic defeat of the royal army and its allies on the field of Mohács in August 1526.

The Fugger family, who dominated a part of the imperial and royal courts in medieval Europe, was discussed earlier during the trial of the Hunya family. Emperor Charles V of Habsburg, the "lord of half the world", took out the biggest loans from them. The emperor then paid back the huge sums borrowed from the Fuggers to the banker family at interest. There was plenty of it, since the plundering of the Spanish colonies brought enormous income to the court. As a result, the emperor's brother, King Ferdinand I of Hungary, also became an employee of the banking family from 1526. It is true that earlier, in 1495, János Thurzó, a lord of the Highlands, concluded a contract with the Fuggers. According to this, the income of the gold, silver and copper mines of Besztercebánya and its surroundings was taken over by the banking family, and they even created a joint business in minting coins. However, another "businessman", Imre Szerencsés (Fortunatus), who fled Spain to Buda, intervened in the business of the Fuggers (as the Hungarians called them, the stingy ones). Szerencsés was accused of fraud, and Fugger party supporters robbed his house in Buda, but he did not give up the fight for the big profit. Sértsésé accused the Fuggers of fraud in the 1960 parliament. The case reached the Pope, who, in alliance with Charles V, threatened the Hungarians, writing a letter to II. To King Louis: "Strongly advocate and demand that justice be served to the Fuggers!" They "delivered justice" to the Fuggers, in exchange for which Hungary received a HUF 50,000 loan, which was almost not enough for anything. The plight of the country was compounded by the fact that Sülejmán Nagy embarked on his conquest campaign against the Kingdom of Hungary just in these days - perhaps not by chance. The mine work of the Habsburgs also contributed to the tragic defeat of the royal army and its allies on the field of Mohács in August 1526.

This economic policy continued in the 19th century, only then the Rothschilds controlled Europe's finances. The founder of the dynasty from Frankfurt, Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812), created the largest banking network in Europe. Among his children, he placed five of his sons in Frankfurt, London, Paris, Naples and Vienna. The five children founded their own bank in that country.

The motto of the Rothschilds: Harmony, Honor, Diligence.

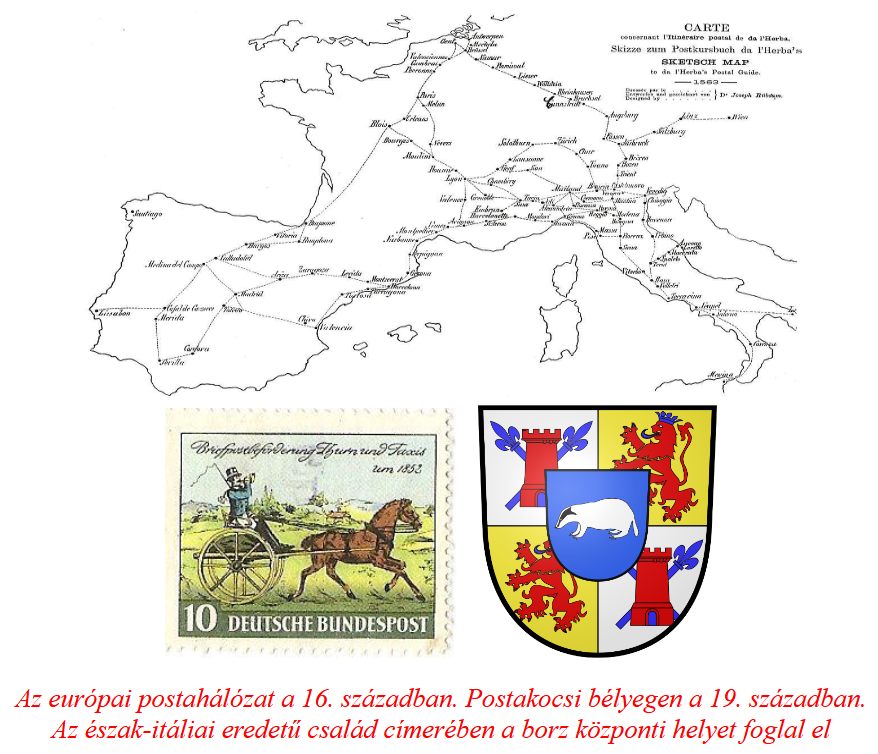

The insight of the Rothschilds was proved by the fact that they used and paid well for the postal network of the ducal house of Thurn & Taxis, which they also used as a courier service. They realized what is now a cliché, that information is power. Because of course, the most important letters were opened and read by specialized officials, and the first users of the information contained in them were the Rothschilds. (An example of this fast courier service is the decisive role of being the first to receive news of the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo in the series 69.) The Thurn und Taxis family became related to the Batthyány and Esterházy families through marriages in the 18th century.

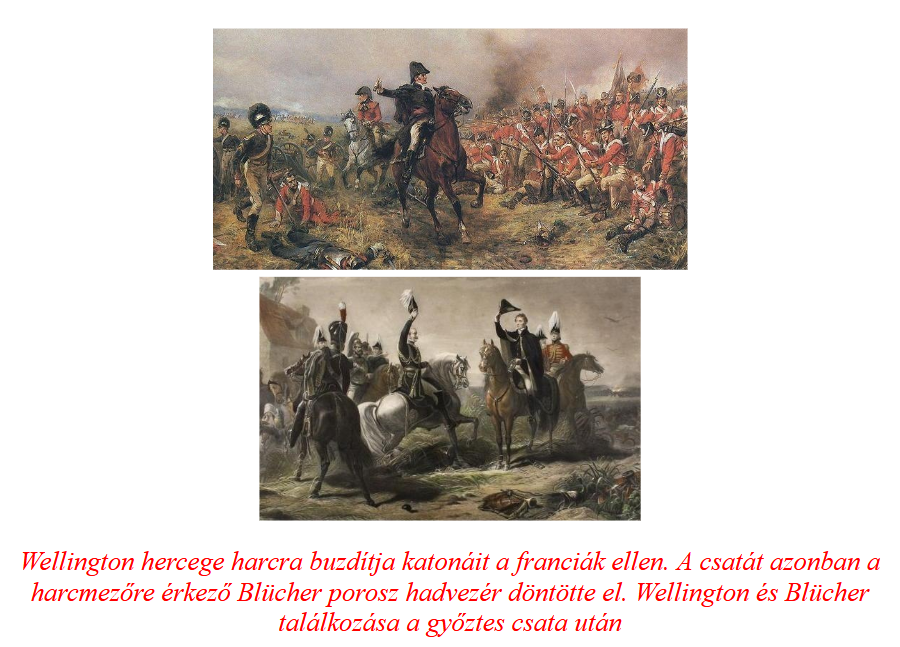

The Rothschilds made their first major international deal in 1804, when the Danish king VII. They helped Krestély out of his financial problems. From then on, European rulers and warring generals, regardless of which side they were on, could count on the financial support of the banking network. Which they then had to pay back with interest. This was also the case during the Napoleonic Wars, when the campaign of the first Duke of Wellington of England was financed. But they supported Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and this support also affected Hungary through Austria.

The Rothschilds made their first major international deal in 1804, when the Danish king VII. They helped Krestély out of his financial problems. From then on, European rulers and warring generals, regardless of which side they were on, could count on the financial support of the banking network. Which they then had to pay back with interest. This was also the case during the Napoleonic Wars, when the campaign of the first Duke of Wellington of England was financed. But they supported Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and this support also affected Hungary through Austria.

Let us mention two politicians who dared to oppose the interests of the European banking network. The first was Napoleon, and one can think about why the liberal democratic United Kingdom and conservative Prussia and Austria joined hands with Hungary against the French emperor at Leipzig and then at Waterloo. The financial support came from one place, the Rothchilds. (The other politician who also wanted to become independent from the Viennese banking house was Lajos Kossuth.)

After the fall of Napoleon, which was a huge benefit for the banks, the dynasty got its hands on the government bonds of the Western powers. The other source of great benefit was the process of the industrial revolution that overturned history, society, technology, and culture. The Rothschilds financed the development of machinery, factories, the railway network, shipping, and the opening of mines, but in the middle of the 19th century they were also involved in the production of wine and champagne, horse racing and the collection of art treasures. Money

and influence made it possible for the Rothschilds to enter the highest circles of the aristocracy in almost every country.

The big turning point was the Congress of Vienna held in 1814-1815. The victorious countries of Europe celebrated themselves after the victory over Napoleon, while they rearranged the map of Europe. Particular attention was paid to the formation of the territory of Germany and the suppression of French expansion. They also made sure that another revolution could not break out in Europe. The final declaration was signed on June 9, 1815.

After the congress, Tsar Alexander I of Russia, III. King Frederick William of Prussia and Emperor Franz I of Austria created the Holy Alliance, which primarily aimed to suppress revolutionary movements. When England joined in November 1815, the Quadruple Alliance was formed, and these states practically covered all of Europe and brought it under their control.

After the congress, Tsar Alexander I of Russia, III. King Frederick William of Prussia and Emperor Franz I of Austria created the Holy Alliance, which primarily aimed to suppress revolutionary movements. When England joined in November 1815, the Quadruple Alliance was formed, and these states practically covered all of Europe and brought it under their control.

In 1816, the lord of Austria, Emperor Francis I, granted four Rothschild sons noble titles, which Nathan Rothschild also received two years later. In addition, in order to make the relationship even closer, in 1822 the five bankers were given the title of Freiherr, which gave them even more room for maneuver in Central Europe. It is no coincidence that the Oesterreichische Nationalbank, or Austrian National Bank in Hungarian, was founded in 1816, which was entirely privately owned by the Rothschilds.

The first bank in Pest was founded by some Jewish merchants from Budapest at the initiative of Count István Széchenyi. Pesti Kereskedelmi Bank started its operation in 1841. Ullman Mórico was chosen as its first director. This financial institution was the only commercial bank in Hungary until 1867. (In most European countries, central banks were born in the middle of the 19th century.)

(The Magyar Nemzeti Bank celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2024. After all, the MNB was officially founded in the Horthy era, on June 24, 1924. It should be known that the Hungarian bank, which was planned to be independent, could not start operating until 1694 They didn't take out a loan from the Bank of England, founded in 1988. Bethlen and Horthy tried to resist for three years, until finally taking out a loan of four million after 1927, the new money, the pengő, held its value until 1944. After that, there were organizational changes, but the legal continuity was preserved for this hundred years, since the central bank functions then was also practiced by various financial institutions.)

(The Magyar Nemzeti Bank celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2024. After all, the MNB was officially founded in the Horthy era, on June 24, 1924. It should be known that the Hungarian bank, which was planned to be independent, could not start operating until 1694 They didn't take out a loan from the Bank of England, founded in 1988. Bethlen and Horthy tried to resist for three years, until finally taking out a loan of four million after 1927, the new money, the pengő, held its value until 1944. After that, there were organizational changes, but the legal continuity was preserved for this hundred years, since the central bank functions then was also practiced by various financial institutions.)

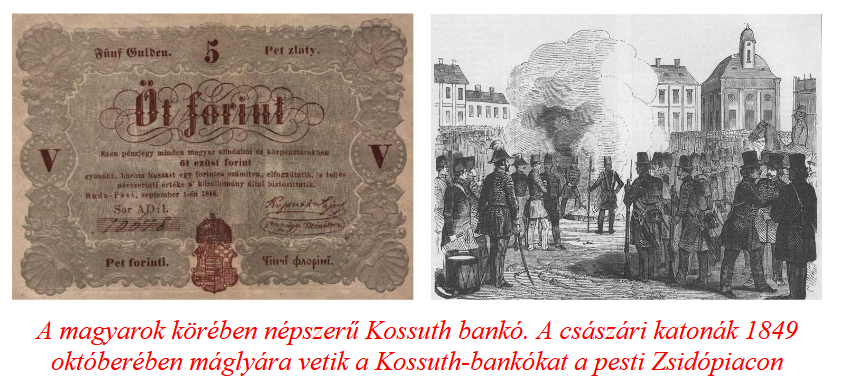

After the aforementioned Pesti Kereskedelmi Bank, in 1848/1849. during the war of independence in 1988, although a new financial institution was not established, the cause of the war of independence had to be supported. This was also enshrined in law, since among the demands of the 12 points of the revolution,

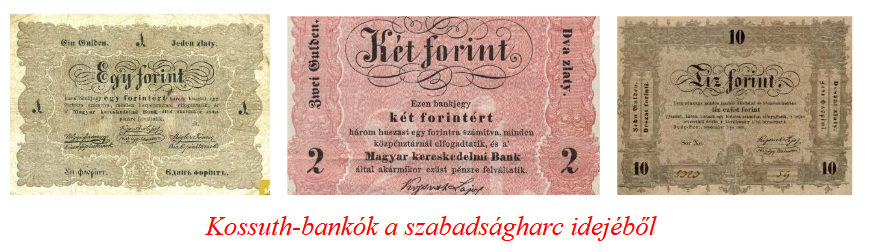

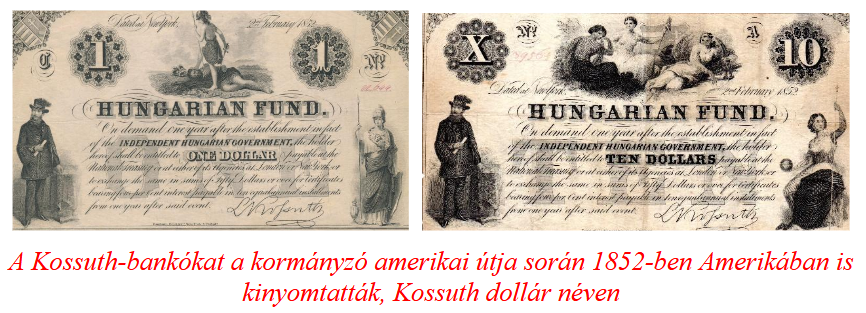

the 9th point was about the establishment of the National Bank. It was then that the Kossuth banknotes were issued through the Commercial Bank. It was covered by the donations, jewels and other offerings of the Hungarian people - who could. In addition to his other abilities, Kossuth was also an excellent economist.

The paper money that became legendary was produced on the machines of the Landerer printing house and was put into circulation on August 6, 1848. Among the paper money of the time, the Hungarian banknote was considered world-class with its design and the quality of the paper that protects against forgery. The first banknote was the HUF 2, which was followed by HUF 1, 5, 10 and 100 denominations. A 1,000 HUF note was also produced, but it could no longer be put into circulation. Due to the lack of change, it became customary to break up the bank, thus alleviating the lack of change. Change money was also made, but very little of it was in circulation.

The paper money that became legendary was produced on the machines of the Landerer printing house and was put into circulation on August 6, 1848. Among the paper money of the time, the Hungarian banknote was considered world-class with its design and the quality of the paper that protects against forgery. The first banknote was the HUF 2, which was followed by HUF 1, 5, 10 and 100 denominations. A 1,000 HUF note was also produced, but it could no longer be put into circulation. Due to the lack of change, it became customary to break up the bank, thus alleviating the lack of change. Change money was also made, but very little of it was in circulation.

After the battle of Temesvár on August 9, 1849, the Austrians seized the printing presses and printing plates, collected the Kossuth banknotes under threat and destroyed them. The fiercest enemy of the first Hungarian money was Windischgratz, presumably on behalf of the Viennese banking world.

After the battle of Temesvár on August 9, 1849, the Austrians seized the printing presses and printing plates, collected the Kossuth banknotes under threat and destroyed them. The fiercest enemy of the first Hungarian money was Windischgratz, presumably on behalf of the Viennese banking world.

They wanted to erase even the memory of the money of the war of independence. Not only because he was a symbol of the freedom struggle, but also because he dared to oppose the interests of the Rothschilds. Already in 1848, Windischgratz ordered that the banknote must not only be destroyed, but whoever is found with it must be severely punished. Due to the harsh behavior of the Court, the Hungarians treasured the banks more and more and, like precious relics of the freedom struggle, hid them from the authorities. The confiscated money was spectacularly burned not only in Pest, but also in the main square of the larger cities, thereby intimidating the rebellious Hungarians. (The paper money only got the name Kossuth bank later, after the war of independence was defeated.)

After the war of independence was defeated, the central bank of Vienna managed the issuance and supervision of the money in circulation in Hungary. The compromise did not change this either, although Hungary became independent in many matters, but not in financial matters. This will be discussed in more detail in the next section. József Ferenc could not have given Hungary freedom in financial matters, even if he wanted to, because his hands were also tied, since the banking network of the entire empire was 100% owned by the Rothschilds. The compromise of 1867 will bring the true financial vulnerability of the Hungarians.

Ferenc Deák during the provisional period (1861-1865)

The tragic death of László Teleki had a chilling effect on Hungarian political life. Deák was also affected by the loss of his political opponent. He retreated into passivity. He read a lot, lived his life according to a schedule in the English Queen Hotel, but in fact he was preparing for the next big competition.

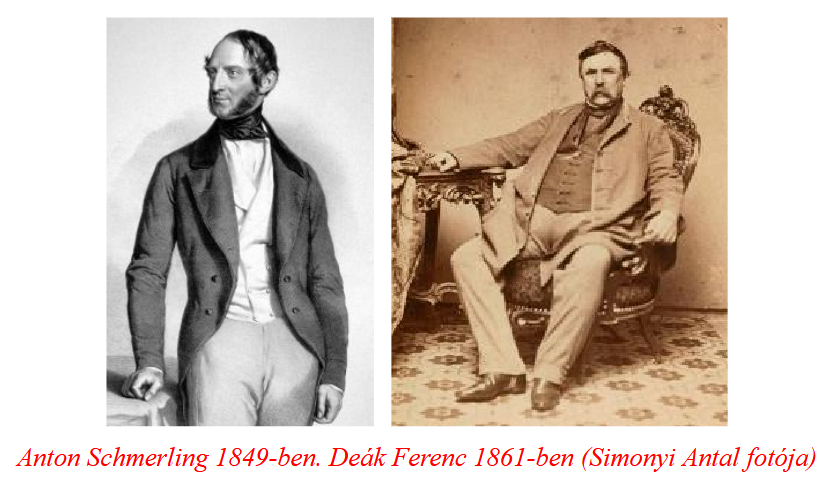

Some of the nobility felt that passivity was not the answer. Given that the land had slipped from under their feet in the meantime, the debt had a depressing effect on them. In the meantime, the Viennese Minister of State, Anton Schmerling, only said, "We can wait!". This was all the more dangerous because Ferenc József dissolved the county governing bodies in November 1861.

Furthermore, the monarch expanded the powers of the military courts, i.e. the Schmerling Provisional Order, or "temporary state" in Hungarian, was introduced. Conservative politicians have activated themselves. They favored the need for a responsible government, but at the same time insisted on setting up ministries of common affairs. There was a lot of traffic at the English Queen Hotel. Every day from nine in the morning until half past one, Deák received visitors in his usual place. Strangers often asked him for money, knowing Deák's soft heart and giving tendency. In each case, a small amount was prepared for this purpose, which then regularly found its owner.

Deák was apparently not involved in politics between 1861 and 1865, but he was all the more active in literary, artistic, and scientific public life, as his visitors prove. Zsigmond Kemény, József Eötvös, Ágoston Trefort, Antal Csengery and many other writers, poets, lawyers and public figures were more inclined to compromise and liberal views. Deák was also visited by leading Serbian and Croatian politicians, with whom he discussed nationality matters. On this subject, Deák envisioned a policy similar to that of Kossuth, who published the draft of the "Danube Alliance" in May 1862. In addition to Kossuth, György Klapka, Ferenc Pulszky, and Ignác Helfy took part in the work. The latter published Kossuth's draft in Hungarian, and later the work was also published in Italian. Deák knew that the relationship between Vienna and Pest would only be harmonious if the nationalities did not become our enemies.

History of the Easter article. In 1862, an Austrian lawyer, a certain Wenzel Lustkandl, published an article that criticized the deacon's interpretation of Pragmatica Sanctio. It was full, because it should be known that Ferenc Deák has been the III. It started from the law issued by Emperor and King Károly in 1723, when it proved the continuity of the Hungarian legal order. This was much more than enshrining female inheritance in the law, it encompassed several centuries of history of the Hungarian legal system. This will also be the basis of the compromise, which was valid for the legal continuity of either the April 1848 or 1861 parliamentary draft laws. No one knew the paragraphs of Pragmatica Sanctio better than Deák. This was questioned by the Austrian Lustkandl, who even denied that the Hungarian orders had the right to freely elect a king before 1526 (Mohács). He did it to his loss, because all of Deáké's propositions were refuted and turned to the advantage of the Hungarians.

Deák and his colleagues started formulating the appropriate answer as early as 1862, but then put it aside and did not deal with it again until the end of 1864. As Deák writes: "Mr. Lustkandl did not write Hungarian-Austrian public law, but he wants to support a political point of view and direction with a fragmentary explanation of some points of Hungarian and Austrian public law... this is just a political pamphlet, with the usual clutter and frequent partiality of such pamphlets."

Deák and his colleagues started formulating the appropriate answer as early as 1862, but then put it aside and did not deal with it again until the end of 1864. As Deák writes: "Mr. Lustkandl did not write Hungarian-Austrian public law, but he wants to support a political point of view and direction with a fragmentary explanation of some points of Hungarian and Austrian public law... this is just a political pamphlet, with the usual clutter and frequent partiality of such pamphlets."

The voluminous answer, consisting of five chapters and an appendix, was published in Budapesti Szemle at the beginning of 1865. The long brainstorming was not in vain, as this documented discussion material, accessible to anyone, was a prelude to a much shorter but far-reaching writing, the well-known Easter article.

Author: Ferenc Bánhegyi

Author: Ferenc Bánhegyi

Cover image:

The parts of the series published so far can be read again here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28., 29/1.,29/2., 30., 31., 32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46., 47., 48., 49., 50., 51., 52., 53., 54., 55., 56., 57., 58., 59., 60., 61. 62., 63., 64., 65., 66., 67., 68., 69., 70.