"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated.

Publication of the Easter article (April 16, 1865)

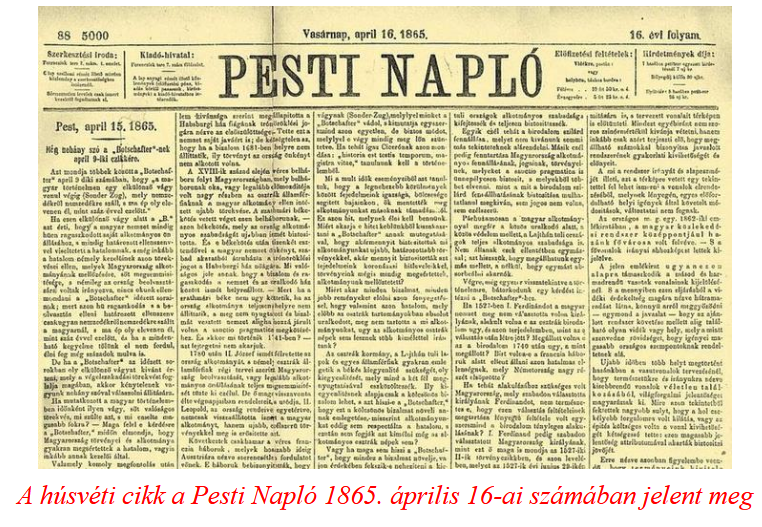

An anonymous article of political life with historical significance was published on April 16, 1865, Easter Sunday, in the columns of the Pesti Napló. This is where the epithet "Easter" comes from. However, it soon became clear that the preparatory document for the Austro-Hungarian agreement was written by Ferenc Deák. However, Deák was serious about anonymity, since the day before in the English Queen Hotel, he told a journalist, Ferenc Salamon, that the editors would not even be able to tell from his handwriting that he was the author.

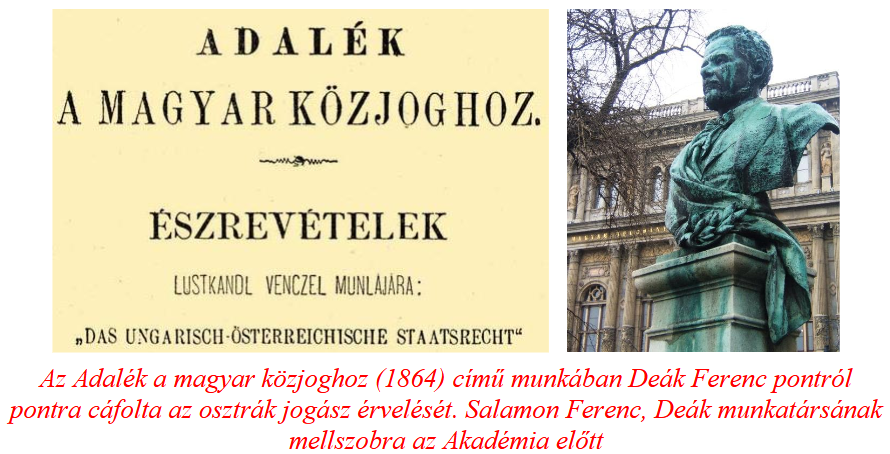

Wenzel Lustkandl's article published in 1862, presented in part 70 of the series, which criticized Deák's interpretation of Pragmatica Sanctio, can be considered the beginning of the political debate leading to the compromise. Deák and his colleagues began to thoroughly answer the incomplete but provocative work of the Austrian lawyer. This work was then put aside, and in 1864 the answer to Lustkandl's article was published. The following year, after another article attacking the Hungarians, Deák openly entered the stage of politics, and as a result, the Easter article was born.

The paper called Botschaffer (Ambassador) attacked the Hungarians, referring to their centuries-old history, based on the false theory of legal evasion. In it, he accused the freedom-loving Hungarians, who often rebelled against the Habsburgs and took up arms, of separatism, because they did not surrender to Vienna, like the Czechs or other Slavic peoples, for example. As they explain, this is the essence of the Hungarians. The opposition, according to the Austrians, the completely meaningless "desire to separate the Sonder-Zug" characterizes this people. And this makes no sense, they write in Botschaffer.

This is said by the Habsburg power, which owes its mere existence to King László Kun, when he helped the insignificant Habsburg Rudolf to the throne in 1278, in the Battle of Moravia. Or when he protected Austria as a shield against the Turks in countless cases, when they strengthened the shaky power of Mária Theresa against the Prussians, or when they tolerated the fact that the Habsburg Hungarian kings who came to power with the Holy Crown on their heads in the coronation church in Bratislava without exception swore to destroy Hungarian freedom. And we are the separatist, separate people!

(You can't help but think that the same thing is happening today. Anyone who can think even a little on a historical scale should see that the Hungarians have the same historical role today, as they accuse us of the same "outsider" characteristics and behavior without reason. )

To prove this, Ferenc Deák set out to defend the thousand-year-old rights of the Hungarian people when he wrote the Easter article.

Deák returned to political life at the beginning of 1865. Even in these years, he was the same thoughtful, honest, determined, invincible debate partner as he was two or three decades earlier. The difference might have been that the experiences of the past decades and the much greater legal, political, and historical knowledge made him even more committed to the defense of the Hungarian cause.

Deák's "years", the period between 1861-1867, were eventful years in both domestic and foreign politics. The harbingers who suggested the modernization of the order structure earlier were the young or neoconservatives. Count Emil Dessewffy and Count György Apponyi tried to push the liberal opposition into the background while cooperating with the court. (Széchenyi did not agree with them, primarily in the matter of maintaining order.) However, the "proctor of the nation" continued the policy of the former chancellor Apponyi and the president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Dessewffy. In his article Additions to Hungarian public law (1865), he stated that the liberals were ready for negotiations. (Under the term liberal, we do not have to mean the liberalism we understand today.)

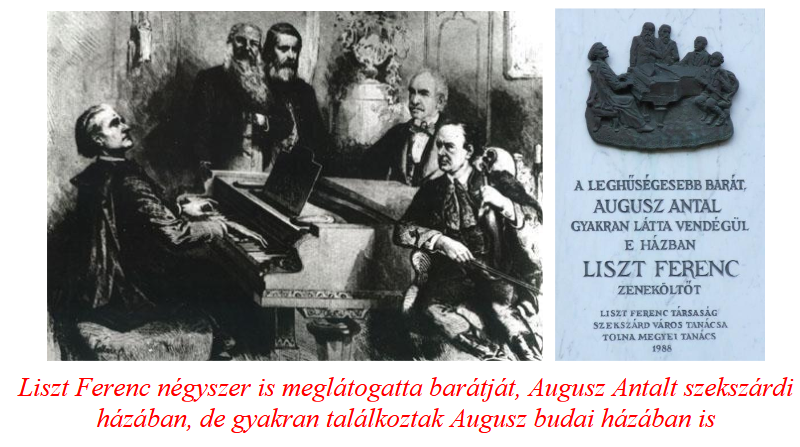

Baron Anton von Augusz, better known as Antal Augusz, a nobleman from Tolna, was a colorful personality of the years before and after the compromise. Augusz was born in Szekszárd and died in his beloved city at the age of 71. The educated, world-viewing, multilingual Antal Augusz received the title of baron from the Austrians, and although he never denied his Hungarian status, he participated in the preparation of the agreement as an emissary of József Ferenc. His good friend was the genius music poet Ferenc Liszt, who wrote the following upon the death of the Tolna nobleman: "The loss of Augusz affects me most painfully. Since the first performance of the Mass in Esztergom - more than twenty years ago - we have been one in spirit. And he was also the one who particularly strengthened my decision to commit myself to Budapest."

These are just a few of the many examples who, in different ways, participated in bringing the settlement under the roof. They did this with faith, with good intentions, in order to pull the country's cart out of the hole.

These are just a few of the many examples who, in different ways, participated in bringing the settlement under the roof. They did this with faith, with good intentions, in order to pull the country's cart out of the hole.

What does the Easter article include? Ferenc Deák believed in the existence of the empire, but within it he firmly insisted on the independence of Hungary. His guiding principle, and his partner in this was the highly respected count Gyula Andrássy (1823-1890), was the inviolability of the Hungarian constitution. And he outlined this with the help of historical examples, when he formulated a historical arc from the end of the 17th century, through the events of the Rákóczi War of Independence, to the birth of the Pragmatica Sanctio and the reign of Mária Theresa. And this is about the fact that the Habsburg-Hungarian alliance was always broken when an emperor or a Hungarian king violated the Hungarian constitution. That's why the Kuruc uprising happened, that's why the hat king (József II) made a mistake, and that's why the 1848/1849 war broke out. revolution and freedom struggle. Don't make this mistake again. Deák's arguments and indisputable historical facts did not impress the hard-headed court conservatives who only thought about the supremacy of the empire. Deák did not enter into the never-ending political debate, all the more so because at that time he received an invitation from a Viennese newspaper to express his views. He wrote a study in the conservative newspaper Die Debatte und Wiener Lloyd, which was published in three parts under the title The May Program. May 7, 8 and 9. However, only the first two articles were published in the Hungarian translation, the third was blocked by the police due to its content. The theme of the May program is the person of the common ruler, foreign policy, the army and finances. The program caused a huge debate in both Vienna and Pest. Several of his fellow politicians harshly criticized Deák for his condescending tone, and warned him that he had embarked on a dangerous path. Even Count Gyula Andrássy got into an argument with Deak regarding the scope of the delegations. Andrássy worked out the establishment and activities of the 60-60-member Hungarian and Austrian delegation.

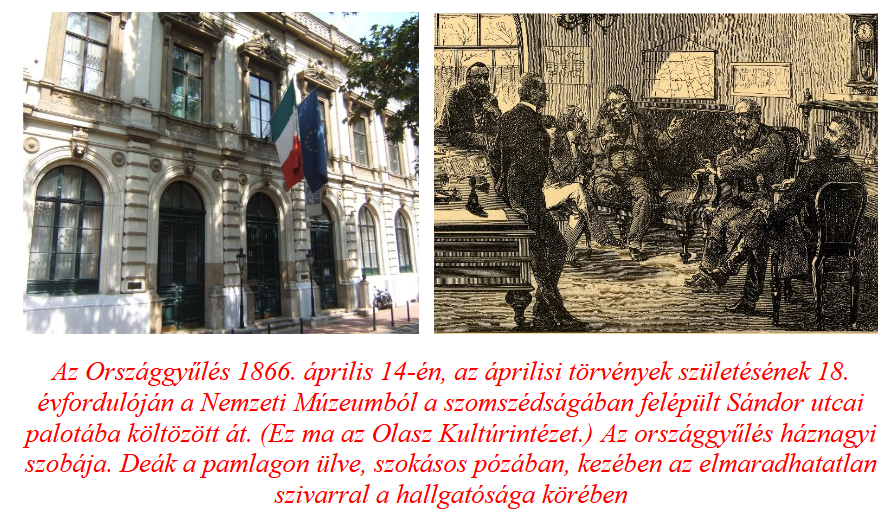

Emperor Francis Joseph personally opened the 1865-1868. Parliament, at which he gave the speech from the throne. In his speech, like Deák, he started from the Pragmatica Sanctió, which was the legal basis for him. Then he defined the most important tasks, which included common matters. The ruler still did not let go of the October Diploma, while the laws of April 1848 could only be discussed after a preliminary revision. For the emperor, only the creation of a strong empire was acceptable. Thanks to Deák's strenuous work, the answer to the speech from the throne arrived in Vienna already on February 27, 1866. Deák did not allow anyone to interfere in the text of the inscription. For this reason, Gyula Andrássy and József Eötvös, his closest colleagues and friends, also faced Deak, whose condition, unfortunately, was showing more and more of his latent illness. The answer, the imperial decree, arrived already on March 3, 1866, which caused enormous disappointment and shock among the Hungarian representatives. The ruler, in his handbook, denied the legal continuity of the April laws. Despite Deák's recurring heart disease, he did not stop working, but at the same time, he worked more and more intensively to reach a settlement as soon as possible. Haste was also in Austria's interest, because it had to prepare for another war.

The parents-in-law sent the second inscription to Vienna on March 24, 1866, which did not change in terms of the demands. However, Deák supported the Hungarian demands with the well-known historical examples, which all proved that the Hungarians never betrayed Vienna, but if necessary, they fought for their truth. The right and left wings of the parliament lined up behind Ferenc Deák. (At that time, the common Hungarian interest was still able to overcome political and ideological divisions.) However, the news was that a Prussian-Austrian war was being prepared. This again divided the representatives as to what would be favorable for Hungary if Austria loses or wins? In these months, Kálmán Tisza (1830-1902) made his voice heard more and more often, who then represented the center-left from the fall of 1866 and then became the leader of the party. And in the summer of 1866, the so-called Committee 67, headed by Count Gyula Andrássy (1823-1890), issued a 65-point proposal on common matters.

The Prussian-Austrian War (1866)

In the midst of political battles, the Austro-Italian-Prussian war broke out. The battles lasted for two months from June 1866, which took place in Italian, Czech, Austrian and German territories. The Prussian and Austrian clashes with hundreds of thousands of armies brought alternating success. The decisive battle took place near Königgratz (today's Czech Republic), in which the Prussians won a decisive victory.

Some of the representatives of the Hungarian Parliament wanted to take advantage of the defeat of the Austrians so that more favorable programs for Hungary appeared in the settlement. The ruler knew this, so he called the parliament again in November 1866, fearing that the Hungarians would back out of the agreement. However, Deák was strongly opposed to abusing the monarch's difficult position. (The Habsburgs also "thanked" the Hungarians for this gesture, as they did so many times during the four centuries - 1526-1918 - not forgetting the Habsburg attacks in the 15th century.)

The real stake of the Prussian-Austrian war was which country could determine the German unity to be created. The Prussians wanted a so-called "Little German" coalition, i.e. Germany, but without Austria, under the control of Berlin. Austria, on the other hand, insisted on the "Greater German" unity, with Vienna as its center. The creator of German unity was Bismarck (1871-1890), the famous German politician and Iron Chancellor. France, which was opposed to German unity, was also defeated in 1870-1871 under the leadership of Bismarck, and the German Empire was proclaimed on January 18, 1871, after the capture of Paris, in the castle of Versailles. The first ruler of the empire (Reich) was Emperor Vilmos I (1871-1888), and its first chancellor (prime minister) was Bismarck.

After the defeat, Austria seceded from the German Confederation, and the victorious Prussia annexed the provinces of Hanover, Hesse, and Schleswig-Holstein. The Italians, allied with Prussia but defeated by Austria, received the rich Venice, which Vienna was forced to give up.

The Compromise (June 8, 1867)

On July 3, 1866, fierce verbal battles raged in the parliament that reconvened. In the middle of July, Ferenc József invited Ferenc Deák and count Gyula Andrássy to Vienna. It should be known that Andrássy did not want to meet the sage of the homeland because of the "Deák concessions", but this was also true for Ferenc Deák, he did not want to sit at the same table with Andrássy either. Ferenc József had a one-hour, face-to-face conversation with Deak, which then accelerated the path to a settlement. The emperor had a good opinion of Deák, but less so of Andrássy. The ruler's opinion about Deák: "... although the old man is very smart, he never had much courage ... I have never found him so calm, clear and honest. It is much clearer than Andrássy and takes into account the rest of the Monarchy much more. Deák instilled in me such great respect for his honesty, openness, and dynastic attachment, ... but courage, determination and endurance were not given to this man." At the meeting, Deák firmly stated that he would not accept any position, but that he had only one candidate for the post of Prime Minister, Count Gyula Andrássy.

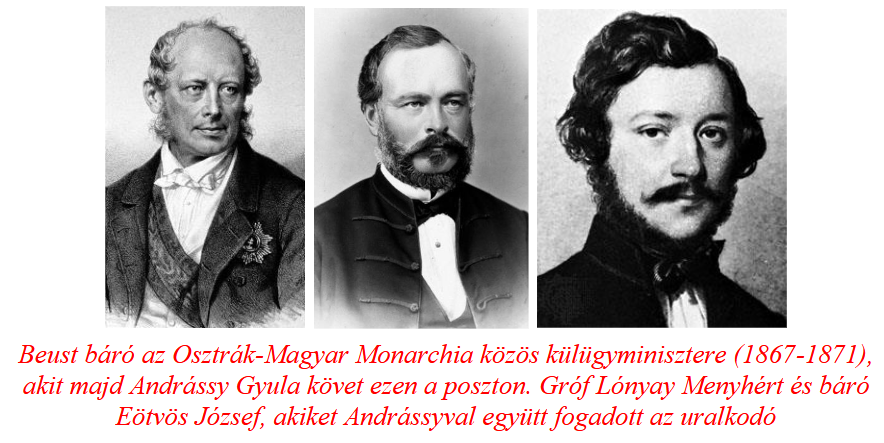

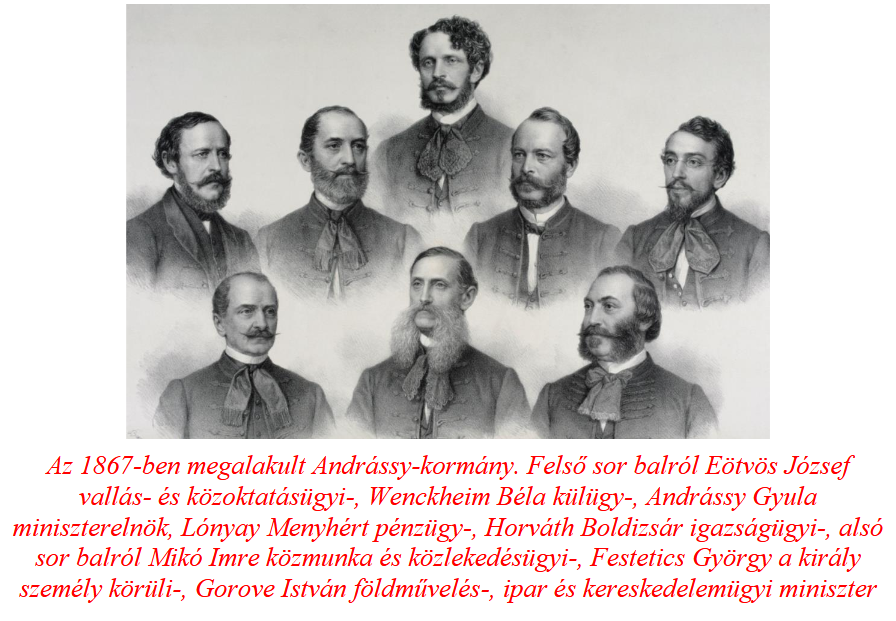

In January 1867, the lower house and then the upper house accepted Deák's new inscription proposal, which, among other things, initiated the withdrawal of the February Patent of 1861. Baron Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust (1809-1886) was a diplomat of Saxony. His name is linked, for example, to the arrest of László Teleki on his way home from emigration, who secretly arrived in Dresden. (More in section 71.). In 1866, during the Prussian-Austrian war, he entered the service of Vienna, which Franz József honored by appointing him minister of foreign affairs and the imperial household. At Beust's suggestion, Andrássy, Lónyay and Eötvös also traveled to Vienna to negotiate, and were also received by József Ferenc. The ruler, who had such a good opinion of Deák, tried to turn the negotiators against Deák, but they declared that they would not do anything behind their leader's back. The Andrássy's basis for negotiations was the establishment of a separate "Hungarian army", but Vienna did not budge on this issue. They discussed loans, the national debt and the renewal, but Ferenc József's hands were also tied in these financial matters. As we have seen before, the Rothschild banking house dominated the Viennese coffers.

During the fluctuating negotiations, Deák once again came face-to-face with Andrássy and his colleagues. In the end, however, they agreed, and then Deák traveled to Vienna on February 7, 1867, as a result of which the monarch appointed Count Gyula Andrássy Prime Minister of Hungary ten days later.

The work of the wise man of the country "brought its fruit". Ferenc József's decree, born on February 17, 1867, enshrined in law the restoration of the Hungarian constitution. Quoting the introductory text: "And as an outcome of this mutual legal basis, we consider, on the one hand, ensuring the survival of the empire and the settlement of related relations, and on the other hand, the restoration of the Hungarian constitution." The 12 legal articles of the transcript were approved by the Hungarian Parliament on March 20-28, 1867. between, which resulted in the text of the compromise law. This includes, among other things, that the Palatine election is postponed, and the prime minister of the Hungarian government is appointed by the monarch. It is about recommending to new recruits that the budget is only valid for one year, and that the monarch can dissolve the Hungarian parliament at any time. It withdraws the article on the national guard, and also states that the relationship between the countries of the empire and matters of the interests of each country are decided by the monarch.

It is no coincidence that decisions on common matters, the budget, the joint bearing of the national debt, the conclusion of the customs and trade alliance, and all financial issues were only made later. The aforementioned Rothschild banking house was behind the financial affairs.

The Kassandra letter

The coronation had not yet taken place, the agreement had not yet been officially announced, on May 25, 1867, the great news of Lajos Kossuth arrived from Turin. The former governor openly opposed the settlement, which he expressed in an open letter. However, the letter My friend! addressed Deák alone. He reminded his old comrade-in-arms of the revolution and freedom struggle carried out shoulder to shoulder, which the wise man of the homeland has now betrayed. He warned his old friend about his own saying, which he had often voiced before: "The right that is lost by violence can be regained, and the only thing that can be lost is that which the nation itself renounced..." Then he listed the setbacks in the army, finances, and common affairs, and again accused the supreme scholar of law of abandoning the law. Not without reason. He did this in the light of that friendship, when Kossuth also referred to the fact that Deák held his child under cross water at the time when he assumed godfatherhood.

Kossuth left his serious accusation at the end of the letter, which reads as follows: "It seems that all this is already trivialized, and the parliament is only called to register the completed fact... But I see the death of the nation in this fact; and because I see this, I consider it my duty to break my silence." Kossuth highlighted this because he has never intervened in Hungarian political life in the past 18 years. But now, when a decision of historical significance was being made, he felt it was his duty to speak out. He warned Deák against accepting the law, but it was too late. The settlement has been made. Kossuth's letter hurt Deák very much, as it broke their personal friendship. In addition, he received about two thousand letters from all parts of the country, most of which were threatening, and the letters argued in favor of Kossuth, sharply criticizing the settlement.

Kossuth left his serious accusation at the end of the letter, which reads as follows: "It seems that all this is already trivialized, and the parliament is only called to register the completed fact... But I see the death of the nation in this fact; and because I see this, I consider it my duty to break my silence." Kossuth highlighted this because he has never intervened in Hungarian political life in the past 18 years. But now, when a decision of historical significance was being made, he felt it was his duty to speak out. He warned Deák against accepting the law, but it was too late. The settlement has been made. Kossuth's letter hurt Deák very much, as it broke their personal friendship. In addition, he received about two thousand letters from all parts of the country, most of which were threatening, and the letters argued in favor of Kossuth, sharply criticizing the settlement.

(The visionary abilities of the Turin hermit were confirmed half a century later, when the curse of Trianon struck Hungary.)

The official conclusion of the settlement, the coronation ceremony

The day of the coronation (June 8, 1867) was already set, the prime minister was agreed upon, the paragraphs were drafted, but there were a few other things that cast a shadow over the holding of the ceremony. The question of Fiume's affiliation caused serious tension. Finally, the Croatian and Fiume representatives were also invited to the ceremony. At that time, however, Ferenc Deák himself put an obstacle in the way of the formal execution of the coronation. Since there was no paladin whose task, among other things, would traditionally have been to place the Holy Crown on the king's head, he waited for the Dea. However, the father of the compromise resolutely refrained from this, he did not even go to the coronation, he shut himself up in the solitude of his home. However, his proposal was accepted so that Count Gyula Andrássy would take care of the Palatine duties.

The ceremony was performed by the archbishop of Esztergom, János Simor, according to ancient custom. Meanwhile, Gyula Andrássy placed the Holy Crown on the head of the new king, József Ferenc. At this moment, Ferenc Liszt's Coronation Mass, written for this occasion, was heard. Next to the ruler, his wife Elizabeth was crowned queen in the Matthias Church. The ruler's plan to shower Deák with all kinds of awards could not be realized. He expressed his appreciation by sending Deák a portrait of himself and his wife in an expensive frame. Deák sent the frames back saying that he could not accept them because they were of great value. Later, he placed the portraits in a frame he carved himself. (Deák requested that the price of the frames and the value of all the awards intended for him be distributed to the widows and family members of the patriots who once fought against Vienna, as well as to the wounded, disabled, and still living freedom fighters.)

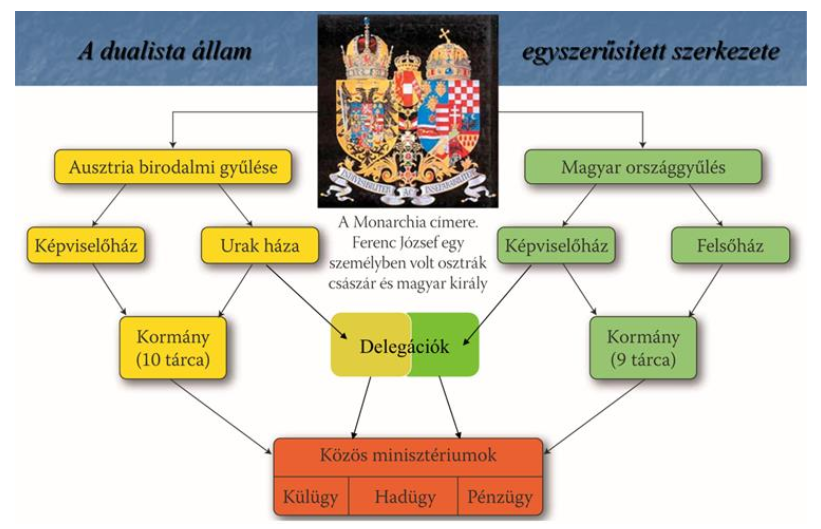

Deák did not participate in the coronation ceremonies citing his illness, but behind his decision was a serious message. He sent a message to the court, the Hungarian Parliament and, above all, to the nation that although the settlement was his work, he still partially distanced himself from it. However, in 1867, with the incorporation into law of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, a state structure was created that has only rarely occurred in the world. Perhaps the Norway-Denmark personal union was similar, but it had a much smaller significance in the history of Europe.

What was the uniqueness of the dualistic system? Two independent countries, two parliaments, two capitals, one ruler, but with two titles, i.e. Austrian emperor and Hungarian king. An office organization was set up to handle common matters. However, many problems remained. One of these was the issue of language. In Hungary, Hungarian remained the official language, but German was the language of command in the army, which then led to a series of political conflicts.

What was the uniqueness of the dualistic system? Two independent countries, two parliaments, two capitals, one ruler, but with two titles, i.e. Austrian emperor and Hungarian king. An office organization was set up to handle common matters. However, many problems remained. One of these was the issue of language. In Hungary, Hungarian remained the official language, but German was the language of command in the army, which then led to a series of political conflicts.

Times of peace, or an era giving rise to new unrest?

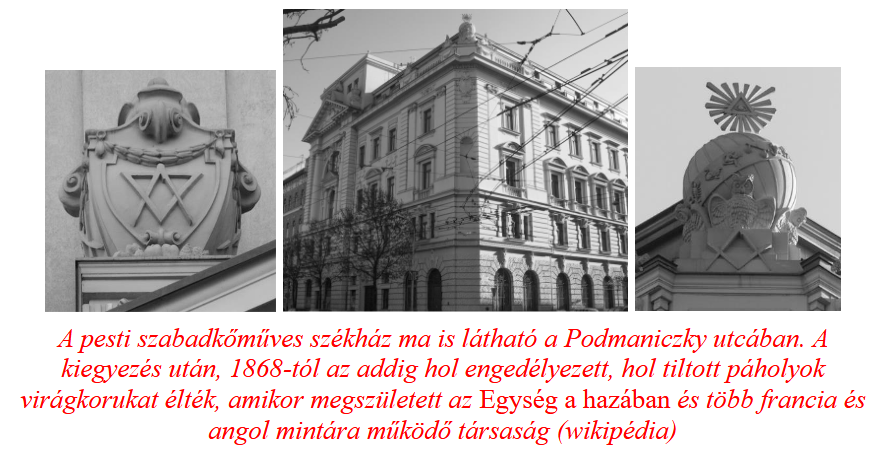

The centuries-old antagonisms and bloodshed between Austria and Hungary have not ceased. However, the years between 1867-1914 resulted in peace, economic development, and social changes in Hungary. We often and proudly mention the incomparably great economic development of the "happy times of peace", especially the constructions that are still the hallmark of Budapest and the larger rural towns. (These will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.) We do not mention that this development came at a very high price. Because, as mentioned earlier, the Austrian and consequently the Hungarian banking system was in foreign hands. The development of large constructions, industry, the railway network and transport in general cost a lot of money, but that money had to be paid back to someone. Those who paid for this were those at the bottom of society, mainly peasants. Masonic lodges were founded or reorganized in these years, which participated in the social transformation in their own way.

Here we can mention the striking lines of Attila József's poem Hazám, written in 1937, according to which "Many of our lords were neither timid nor shy, /to protect their possessions against us,/ and one and a half million of our people staggered out to America." The rhythm of the poem is thus apt, but far more than one and a half million, i.e. two million or even more, emigrants left Hungary. This popular movement, which affected nationalities just as much as Hungarians, meant the destruction of the world-class agricultural sector. Profit-seeking large-scale industrial agrarian enterprises bought up the lands of small farmers, making them homeless. The era of peaceful times presented as idyllic was also an era of serious conflicts, which also involved political clashes with deadly victims. Poverty, internal tensions, emigrants resulted in so many human losses that subsequent eras have not been able to fully replace either. However, let's not ignore the fact that while Europe, and primarily its eastern half, was ruined, the United States of America, which was turning into a world empire in those years, gained considerable material and intellectual wealth. (Perhaps even today, between 2022-2025, we can experience a phenomenon similar to this, coupled with a destructive war.)

Here we can mention the striking lines of Attila József's poem Hazám, written in 1937, according to which "Many of our lords were neither timid nor shy, /to protect their possessions against us,/ and one and a half million of our people staggered out to America." The rhythm of the poem is thus apt, but far more than one and a half million, i.e. two million or even more, emigrants left Hungary. This popular movement, which affected nationalities just as much as Hungarians, meant the destruction of the world-class agricultural sector. Profit-seeking large-scale industrial agrarian enterprises bought up the lands of small farmers, making them homeless. The era of peaceful times presented as idyllic was also an era of serious conflicts, which also involved political clashes with deadly victims. Poverty, internal tensions, emigrants resulted in so many human losses that subsequent eras have not been able to fully replace either. However, let's not ignore the fact that while Europe, and primarily its eastern half, was ruined, the United States of America, which was turning into a world empire in those years, gained considerable material and intellectual wealth. (Perhaps even today, between 2022-2025, we can experience a phenomenon similar to this, coupled with a destructive war.)

It would go a long way to analyze how the United Kingdom and the United States of America, or more simply the Anglo-Saxon powers, came to be at the top of the world a hundred years ago. It is enough to give the answer with a few questions. What language is spoken in Australia today? Did natives live there? What language is spoken in North America today? Did natives live there? We could also ask the question in the case of India, China, Africa and many countries in Asia, not to mention the extensive English-speaking and cultured states of the oceanic archipelago.

The advantages of compromise and the hidden disadvantages will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

The advantages of compromise and the hidden disadvantages will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

Author: Ferenc Bánhegyi

Cover image source: Hungarian National Archives

The parts of the series published so far can be read again here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28., 29/1.,29/2., 30., 31., 32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46., 47., 48., 49., 50., 51., 52., 53., 54., 55., 56., 57., 58., 59., 60., 61. 62., 63., 64., 65., 66., 67., 68., 69., 70., 71.