"A nation that does not know its past does not understand its present, and cannot create its future!"

Europe needs Hungary... which has never let itself be defeated.

Mária Terézia , the "good empress", painstakingly ensured that Hungary, part of the empire, remained among the subject peoples, and did not raise her head, as she did during the Bocska or Rákóczi freedom struggles. Because it is true that the Hungarian nobles gave their "lives and blood" for the empress, it is true that András Hadik brought glory to Mária Theresa, but if there was "resistance" that he did not like, then the Madefalv Massacre followed, during which two hundred Szeklers were slaughtered in the imperial soldiers. Twice as many Szeklers were dragged to prison, where they were kept in inhumane conditions.

Petőfi 200's rich library of events, lectures, books, exhibitions, internet materials, and compilations for children and youth that have been published so far satisfy the needs of all layers of Hungarian society. The program "Great people of the Reformation - for little ones" presents Petőfi and his time in the language of elementary school students. After that, each age group can choose from the basket of abundance if they want to get to know the reform era, including the incomparably rich storehouse of Hungarian history, literature, music, fine arts, and sciences.

With my modest resources, I only undertake to present one slice of Sándor Petőfi's

Sándor I. Petőfi in the Hungarian public consciousness

II.

Júlia Szendrey's role in Petőfi's life III. What happened after Segesvár (1849)?

Sándor I. Petőfi in the Hungarian public consciousness

Historical heroes, literary greats, vanguards of science appear in the most spectacular way in the form of public sculptures before the man on the street. Szent István and Lajos Kossuth, most of the statues in the Carpathian basin depict Sándor Petőfi, which we can see when we visit any corner of the country. Perhaps the most well-known is the statue in Petőfi tér, next to Március 15. tér, in downtown Pest. The other oldest statue, more than 100 years old, can be seen in Kiskunfélegyháza.

One of the best-known buildings associated with Petőfi, which reminds us of the great poet, is the birthplace in Kiskőrös.

There is no settlement, even the smallest village, without a Petőfi street, a Petőfi square, or a school, community center, or any other public building named after him. It is no coincidence that the conscience of our nation, because Petőfi also fulfills this noble role, had to endure many humiliations and trials in the annexed Trianon territories even in his dying days. To this day, the Tótoks (who sometimes even consider the István Petrovics and Mária Hrúz ), the Oláhs, the Ráks, and the Ukrainians want to erase his memory in the abducted territories. That is why they are destroying his statues, memorial plaques, buildings and memorials connected to Petőfi. However, there have also been confidence-inspiring attempts, such as in Transylvania in Nagyvárad, Koltó, Szeged and many other places.

The Petőfi family

Here it is worth briefly dealing with the claim made in 2014, according to which Sándor Petőfi is actually the child of count István Széchenyi . The quoted sentence is included in Széchenyi's memoirs from Döbling, which, knowing Széchenyi's capricious nature and visionary skills, can be interpreted in many different ways. "and all the seers who have attacked lately, such as Petőfi, who is my son, whose mother I let die like so many others" .

I would not go into the expression my son, which Széchenyi did not describe literally, without analyzing what the expression "let me die" means in the interpretation of an aristocrat referring to his conscience. Everyone who gives credence to the statement should only know the fact that István Széchenyi and his friend Miklós Wesselényi took part in a joint trip to England from March 1, 1822 to October 20, 1822, which both Széchenyi and Wesselényi wrote in their daily diaries. . The biological father of Sándor Petőfi, born on January 1, 1823, could not have been Széchenyi, even if he had a reputation as a famous womanizer.

The disgraced Petőfi statues

Based on the research of Dr. József Tarjányi, we know that the memory of Sándor Petőfi is immortalized in 416 statues, 180 monuments, and 145 plaques around the world.

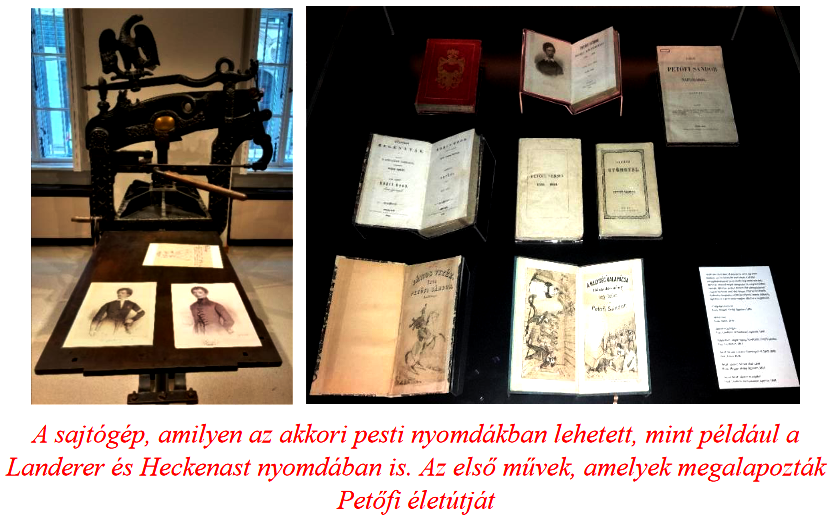

Petőfi Literary Museum

The exhibition opened in 2023 at the Petőfi Literary Museum was built on the basis of the most authentic, latest research. "Since 1957, six permanent exhibitions have alternated in the building of the Károlyi Palace, in the following years: 1959, 1973, 1984, 1990, 2000, 2011". The quote appears in the introductory text of the exhibition. A common element in all seven exhibitions is the presentation of the biography of the great poet. The technical solutions may change, the world view has also changed - as a regime change has intervened - in the past forty years, but the essence of the exhibition is Sándor Petőfi's life, poems, and despite his short life, his inexhaustible work.

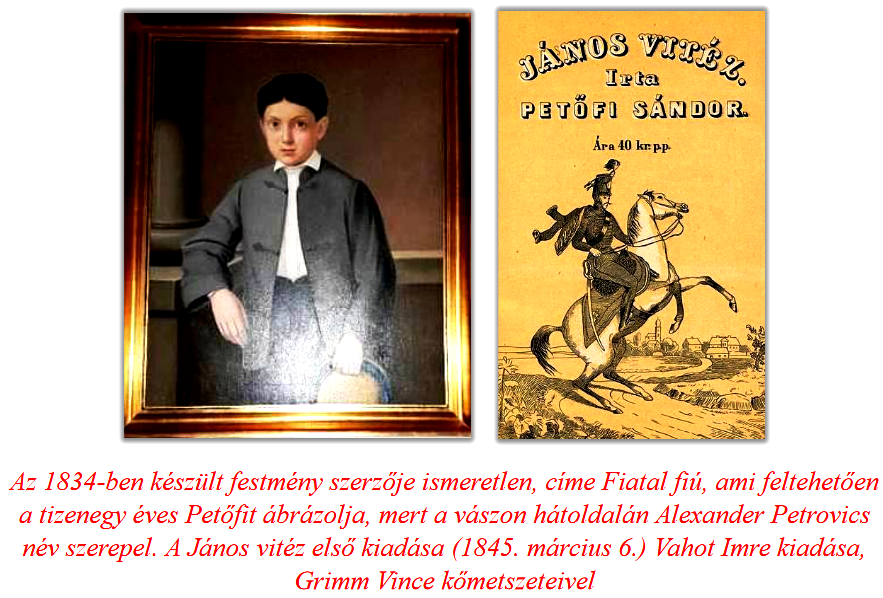

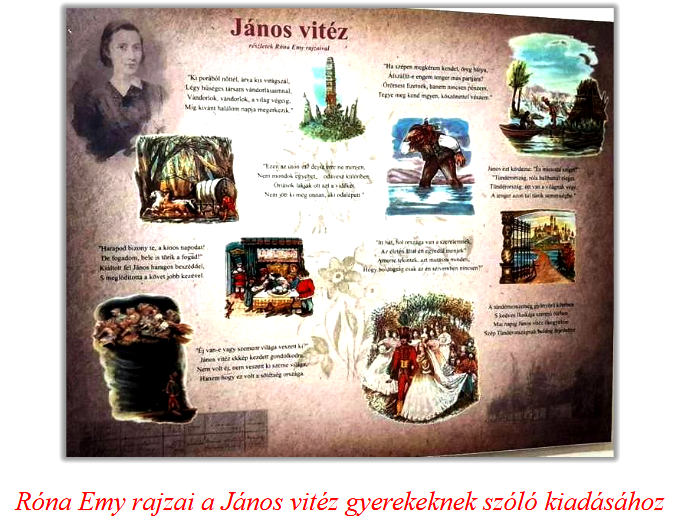

Petőfi prepared his first collection of poems at the age of 16, but it has not yet been published as an independent volume. But he tried again and again, because his inherent talent and desire to create made him do this. Finally, in 1844, with the support of the National Circle, his first volume was published under the title Poems. From then on, as when the sluice is being opened, he poured out his poems, but the heroic poem The Hammer of the Place was also published in this year, 1844. His talent and creative richness are indicated by the fact that in 1844 the English novel Robin Hood His volume Pearls of Love in 1845, followed by his true breakthrough work, the poetic tale of the brave János in 1844, which achieved national success through a competition.

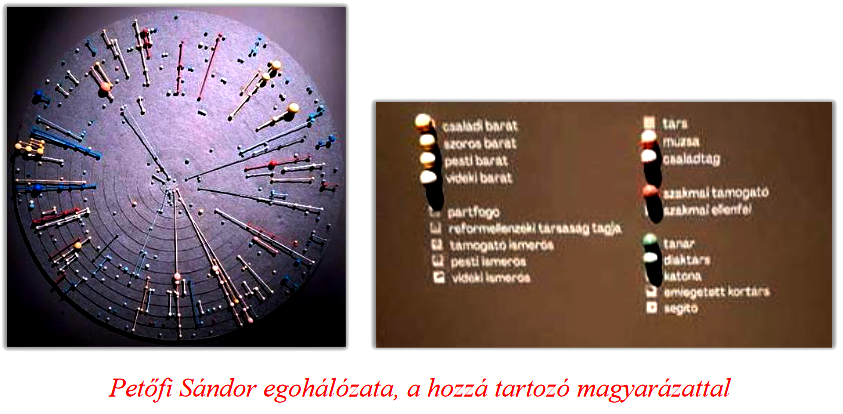

Many people knew Petőfi, and this number grew over the years as his works were published. He also knew many people, but just as people live their lives today, their acquaintances branched out in many directions. Friend, enemy, companion, muse, relative, acquaintance, patron, teacher, student. The staff of the Petőfi Literary Museum did a tremendous job when they compiled the so-called Ego Network of Petőfi from the available data. Among other things, it can be read on the panel that, for example, when Tompa had a fight with Mihály, Tompa burned all his correspondence with Petőfi, which unfortunately contained a lot of interesting and irreplaceable data.

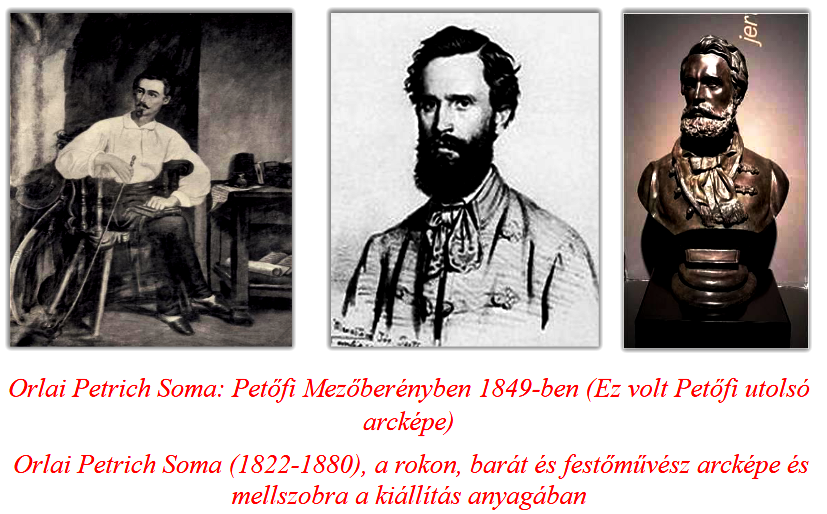

Petőfi in Mezőberény

Petőfi visited the small town of Békés several times, where his cousin Orlai Petrich Soma lived, with whom Pápán went to high school. He spent a month in Mezőberény for the first time, to which he returned several times. The poet wrote several poems in Mezőberény, the outlaw theme Büngözsdi Bandi can be proven, since Bungözsd is one of the wastelands around the small town. His last visit took place in July 1849, when he hurried to join Bem's army and stayed here with his wife and small son. His last poem, Terrible Time, was born here.

It should be known about Petőfi that he was almost constantly on the road. He traveled by foot, cart, stagecoach, itinerant actors, and even on the first Hungarian railway line, the Pest-Vác train. The latter took place on July 15, 1846, when Palatine József arrived in Vác with the participation of his family and friends among the 250 invited guests. Just then, a raging fire greeted the celebrating party in the city. His poem Vasúton, written in December 1847, testifies to this experience. His prose entitled Travel notes enriches the great poet's travels with many details. He loved traveling, as more and more people know him, he is received with great respect, in many places with torchlight processions, he is celebrated and entertained. It is thanks to his travels that Petőfi is remembered in many settlements.

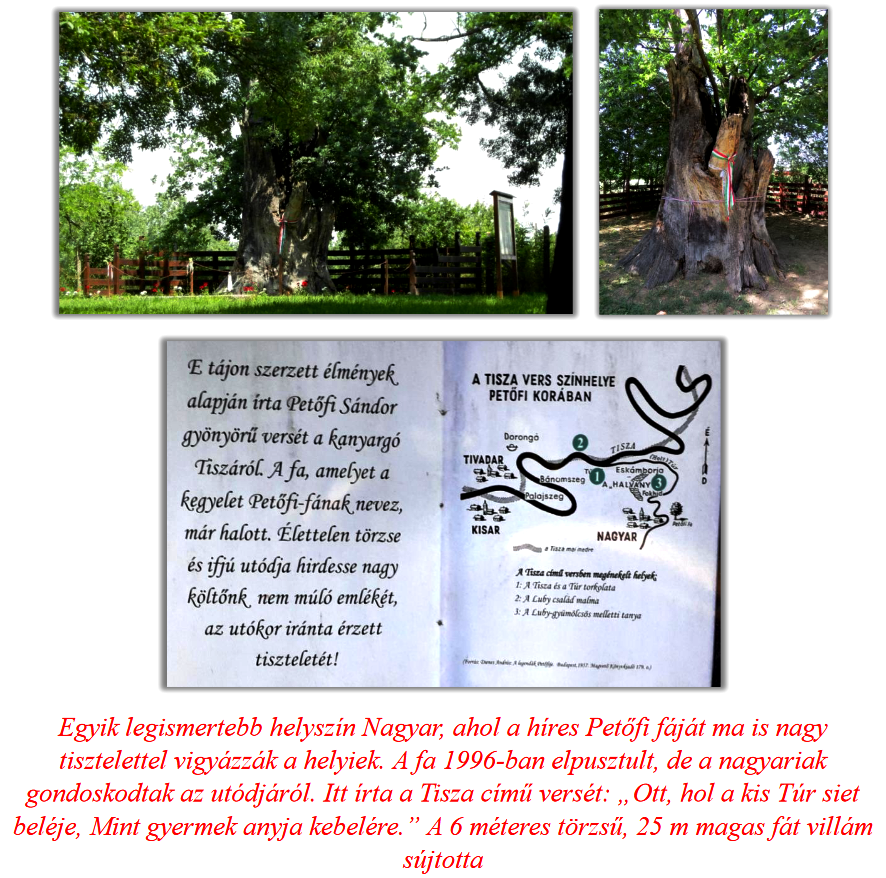

Petőfi visited this region in 1846, he also visited the grave of Ferenc Kölcsey He met , Zsigmond Luby and János. This castle is the only one in the county that stands in its original form, as Petőfi could see, and in which he spent several days.

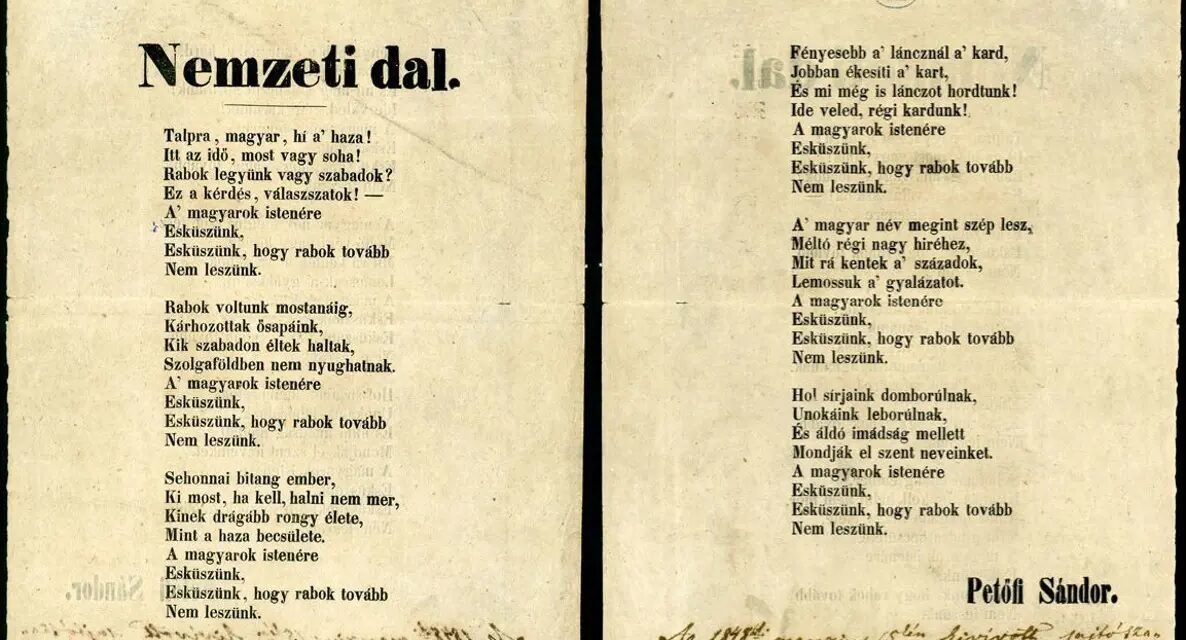

March 15, 1848. The National Song

In Bratislava, on March 3, 1848, Kossuth's famous and history-shaping inscription proposal was announced in the lower house, which the upper board postponed sending. In his anger, Petőfi therefore wrote his poem "Dicőséséges nagyurak" (Dicősésés nagyurak) in his anger, which once again encourages brutal violence, which appeared in several of his poems.

However, this surprised even his friends organized in Pilvax. The poet burned the manuscript, but it was too late. The text is spread. He got into trouble later, he angered several high-ranking politicians and leaders. A similar effect was caused by Hang the kings!, published in December 1848. his creation entitled.

All of Petőfi's poems, all of his personal appearances, wherever and whenever, were unadulterated political statements.

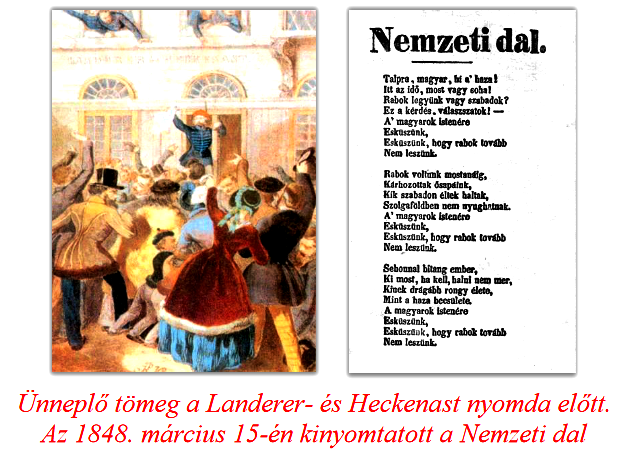

The iconic location of the political career of Petőfi and his colleagues is the Pilvax café in Pest, which is forever linked to March 15, 1848, one of the most significant events in Hungarian history. This day, which marked the beginning of the establishment of the first independent Hungarian government, as well as the 1848/49 war of independence, was undoubtedly Petőfi's day. A similar location for the revolutionary day is the National Museum building, as well as several locations in Pest and Buda, of which only a few can be seen in their original state.

Petőfi and his friends, together with the Opposition Circle, prepared for March 19, 1848, when they planned a feast and a demonstration to put pressure on the Diet in Bratislava. On March 13, the leader of the revolution wrote the National Anthem for this occasion. Petőfi was in his element. He sensed the never-to-return opportunity when, upon hearing the news of the Vienna revolution, on March 15 in Pilvax, in the morning hours, the revolutionary core issued the slogan that action must be taken now. Starting from Pilvax, the young people went to the Landerer and Heckenast printing house with the help of the medical and legal faculty, where Petőfi dictated the text of the National Song to the printer's typist by heart, which was printed on the spot.

On the steps of the National Museum, Gábor Egressy recited the National Anthem, while the 10,000-strong crowd celebrated in front of the museum. A crowd went to Buda to free Mihály Stancsics, who was brought to Pest for the evening Bánk bán performance. The performance was interrupted when Gábor Egressy recited the National Song again, and it was later sung to the tune of Béni Egressy Petőfi was already at home by then, the National song "went on its way".

On the steps of the National Museum, Gábor Egressy recited the National Anthem, while the 10,000-strong crowd celebrated in front of the museum. A crowd went to Buda to free Mihály Stancsics, who was brought to Pest for the evening Bánk bán performance. The performance was interrupted when Gábor Egressy recited the National Song again, and it was later sung to the tune of Béni Egressy Petőfi was already at home by then, the National song "went on its way".

The cocarde (meaning cock's comb) is an invention of the French Revolution. Originally, the symbol of the revolution was formed from the colors blue-red-white, and the Pest tricolor bouquet was modeled on this.

Petőfi's historical role did not end on March 15, 1848, as he participated on Bem's Let's note that the protagonists and great men of the reformation period, as well as the revolution and freedom struggle, certainly did not always and in all cases maintain friendly relations with each other. Petőfi and Kossuth, but we can also include István Széchenyi, often showed autocratic and conflicting behavior. Both to each other and to others. However, this does not take anything away from the value of the shapers of the time, in fact, the debates and contradictions in several cases gave further impetus to political life and intensified the opposition to Vienna.

Mór Jókai stated and described for the first time that March 15 is Petőfi's day. The National Anthem and the 12 points represented the soul and focal point of the Hungarian revolution. Petőfi launched a political campaign in May 1848, when he ran as a representative candidate for Szabadszállás, because he was connected to the town, his parents also had a house in the settlement. The opponent's men chased Petőfi away, so his opponent, Károly Nagy became the representative. Petőfi even wanted to fight, he appealed, but the freedom struggle swept away the re-election.

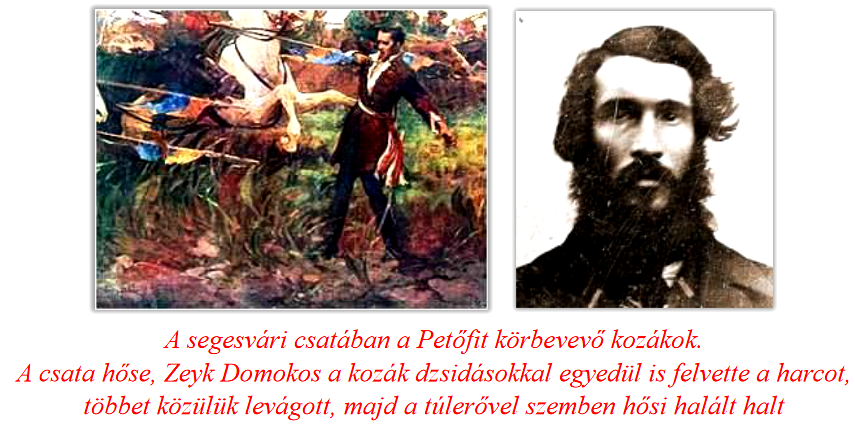

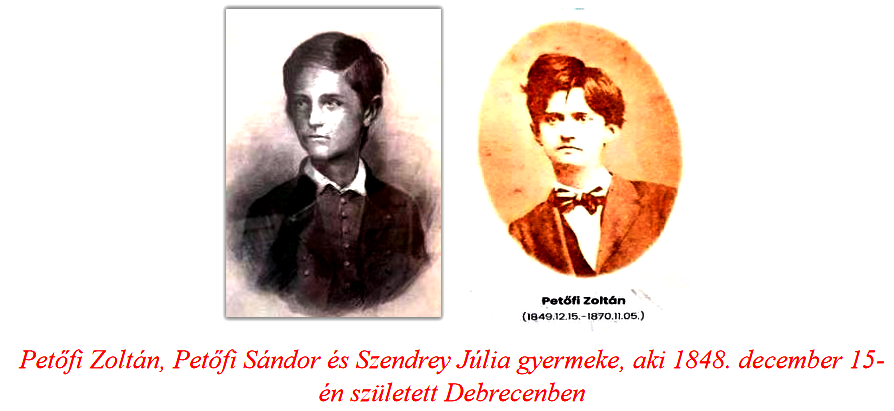

His friendship with Jókai broke off, he fell into depression, and that's when he wrote his autobiographically inspired work, The Apostle. His family relationships hit rock bottom. He took Juliet to her father, Erdőd. He himself went to Debrecen to join Bem's army to complete his military service. Júlia followed her at the end of November, and little Zoltán was born here in Debrecen on December 15. Petőfi then entered into a father-son relationship with Bemm, whom he followed to Transylvania. He also had a serious conflict with Klapka and Lázár Mészáros. Bem appointed Petőfi as captain and aide-de-camp in Sibiu. He did not allow him on the battlefield, because he valued his poetic values more than risking his life as a soldier.

Despite all this, Petőfi entered the battlefield. He was also without a weapon when the Cossack Jiddites overtook him in the corn.

Júlia Szendrey's role in Petőfi's life

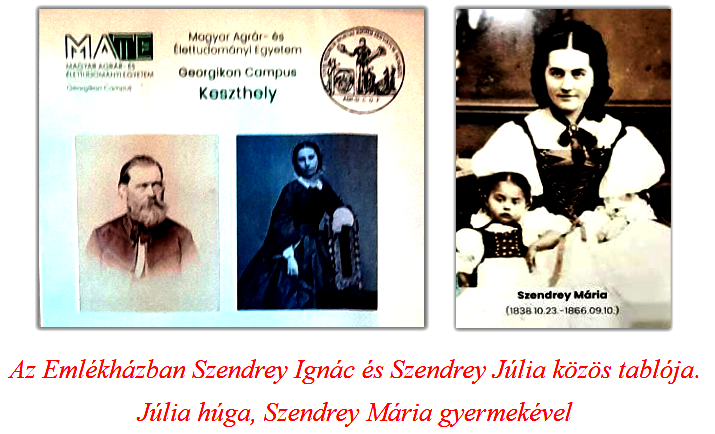

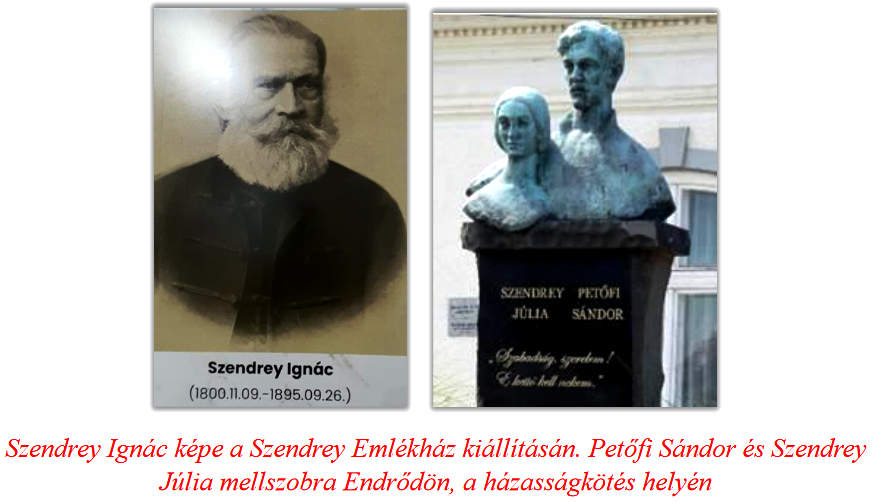

Júlia was born in Újmajor near Keszthely on December 29, 1828, whose first husband was Sándor Petőfi. After the great poet was declared dead, she became the wife of historian and university professor Árpád Horvát her father Ignác Szendrey was the respected farm official of the Festetics estate in Keszthely.

It is interesting that between 1838-1840, Júlia studied in Mezőberény, at the girls' educational institute, where she returned after a four-year detour to Pest. (She also returned to the small town later, when she and her husband visited her cousin, Orlai Petrich Soma, with whom Petőfi spent a lot of time.)

The institutions for girls' education, as well as Júlia's exceptional, eccentric nature, her romantic sense of life, her longing for another life, could unfold in her parents' house. After all, it was piled high with everything he wanted. He got a piano, books, clothes, everything. His father then left Keszthely and went to Erdőd, to the Károlyi estate, where he became the inspector of the estate. Here, in Erdőd, Júlia could truly live her dreams, when she found a safe, beloved home in the lap of the wild, romantic landscape.

Júlia Szendrey played the piano, spoke foreign languages, could dance, and was well versed in the gentlemen's customs of the time. He was a real sociable person. Despite this, he loved solitude, read a lot, played music, and really enjoyed himself when he could deepen his thoughts. He was bored with the bourgeois life in the countryside.

Szendrey first met Júlia Petőfi, the already known and celebrated poet, on September 8, 1846, in Nagykároly. The young and beautiful girl became Petőfi's muse, and wrote the most beautiful love poems for Júlia. Ignác Szendrey was against his daughter's relationship, as he only saw a penniless poet in Petőfi. His candidate for his daughter was Uray Endre

Szendrey first met Júlia Petőfi, the already known and celebrated poet, on September 8, 1846, in Nagykároly. The young and beautiful girl became Petőfi's muse, and wrote the most beautiful love poems for Júlia. Ignác Szendrey was against his daughter's relationship, as he only saw a penniless poet in Petőfi. His candidate for his daughter was Uray Endre

However, the father knew and loved his daughter, after a while he realized that he could not convince her. He did not want to ruin it, so he agreed to the marriage with Petőfi, which took place on September 8, 1847 in Erdőd. Ignác Szendrey's decision was particularly facilitated by the fact that the young couple did not ask for a dowry. They wanted to prosper and control their life together.

Juliet's role model George Sand , the eccentric French writer, she imitated him when, for example, she wore trousers instead of skirts and smoked cigars. He also followed his Parisian role model in that he dealt with a variety of arts - poetry, prose, music, dance, literary translation, theater. Writing and translating fairy tales played an important role in Júlia Szendrey's life. He is credited, for example, with Andersen's fairy tales into Hungarian.

The honeymoon after the wedding was spent in Koltó, with Petőfi's friend, in the castle of the adventurous Sándor Teleki . After that, Ignác Szendrey supported his daughter, who became pregnant in March 1848. These days were the most important phase of their lives, since March 15, 1848 was Petőfi's big day, for which Júlia accompanied her husband with her whole being and talent. She sewed the first cockade and pinned it on Sándor's chest, and she wore a red-white-green head tie.

Petőfi was not present at the Opposition Circle meeting, but we know this because he wrote down how he spent that night, the eve of March 15:

"I spent most of the night awake together with my wife, my brave, inspiring, adored little wife, who always stands encouragingly in front of my thoughts and plans, like a flag raised high in front of an army. We discussed what to do? because it was definitely in front of us that it must be done and at what cost tomorrow... just in case it will be too late the day after tomorrow!"

Petőfi's historical importance lay in the fact that he was able to give a purpose to the revolutionary momentum, he was conscious, he clearly saw that "logically, the very first step of the revolution and also its main duty is to set the press free."

Petőfi also recorded the events of March 15 in his diary. He ran from his apartment on Dohány Street to Pilvax and then returned home:

Petőfi also recorded the events of March 15 in his diary. He ran from his apartment on Dohány Street to Pilvax and then returned home:

"On my way home, I presented my intention to release the press immediately. My companions agreed. Bulyovszki and Jókai edited a proclamation. Vasvári and I walked up and down the room. Vasvári waved my staff, not knowing that it contained a bayonet; at once the bayonet flew straight towards Vienna, without harming any of us. - Good sign! we shouted in unison. As soon as the proclamation was ready and we were about to start, I asked what day is it today? "Wednesday," answered one. "Lucky day," I said, "I got married on Wednesday!"

The days of the revolution, the birth of the April laws, and the establishment of the first responsible government kept the whole country in a frenzy. The Petőfi family also drifted along with the events. The last meeting of the newlyweds took place on July 20, 1849 in Torda, then Petőfi went with Bem's army to fight against the Russians. He left because several people urged him not only to write heroic poems about the battle, but also to prove his personal bravery. Petőfi wrote two more letters from Székelyföld to his wife, and then only the news of his death was brought. Júlia did not want to believe the tragic news. The baby traveled with Zoltán to Cluj-Napoca, where she was waiting for her husband. His father called him home to Erdőd, where he finally arrived with his son in February 1850. He left Zoltán with his father, and he traveled alone to Pest. Before that, he even traveled to Székelyudvarhely and the site of the Battle of Segesvár, looking for Petőfi, but to no avail.

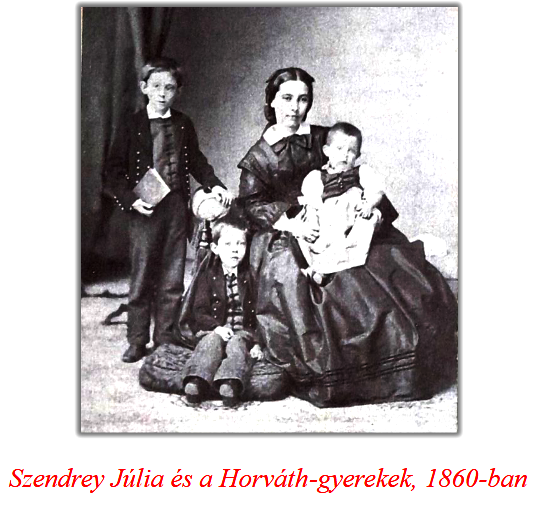

She wanted to travel to Turkey because she hoped to meet Sándor there. But he didn't get a passport. Haynau's confidant, Ferenc Lichtenstein , who wanted to make Júlia his lover in return for his help. In desperation, Sándorné Petőfi Árpád Horváth , and on July 21, 1850, they secretly married. When this was revealed, national outrage accompanied Júlia Szendrey's decision. They could not forgive Sándorné Petőfi for the quick change. János Arany expressed his deep disappointment in his poem A Honvéd's Widow, since the memory of his best friend was muddied by Júlia's premature remarriage. Even if Júlia Szendrey's decision was forced, in the first years the young wife was happy and felt safe with Árpád Horváth. This is proven by the fact that she gave birth to four children to her new husband between 1851 and 1859 (Attila, Árpád, Viola, Ilona), but in the meantime she also tried to take care of Zoltán.

However, Zoltán Petőfi's unstable nerves and behavior that was unsuitable for completing his studies separated him from his mother. He became an itinerant actor, tried to write poems, and with his death in 1870, at the age of 22, the great poet's family tree was cut short. (It is true that István Petőfi had a child, but he was born out of wedlock.)

In the first years of her marriage, Júlia was in her element and worked a lot. Among other things, the most beautiful works of the great Danish storyteller Andersen were published in Hungary in 1856, translated into Hungarian by Júlia Szendrey. In the volume, you can read, among other things, Rendítteteln olomkatona, in which, together with other fairy tales, you can discover many elements of Hungarian children's folklore.

In 1867, Júlia decided to move away from Árpád Horváth, who changed radically after the first happy years. In the meantime, Júlia became ill, she was diagnosed with uterine cancer, but she couldn't stand it any longer with her husband, who was having extramarital affairs, who, for example, kept pornographic newspapers in his bed. The disease quickly overcame the weakened body. Júlia passed away on September 6, 1868, after a long period of suffering, before she was even 40 years old. (The first meeting with Petőfi took place on September 8, the wedding took place on September 8, and he died on September 6.)

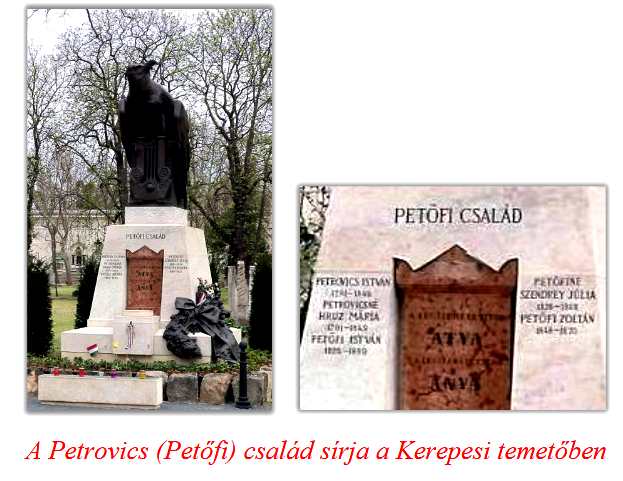

The family grave in the Kerepesi cemetery is worth mentioning. Her daughter's funeral was taken care of by her father, Ignác Szendrey, who died in 1895 at the age of 95, survived by his loved ones and daughters.

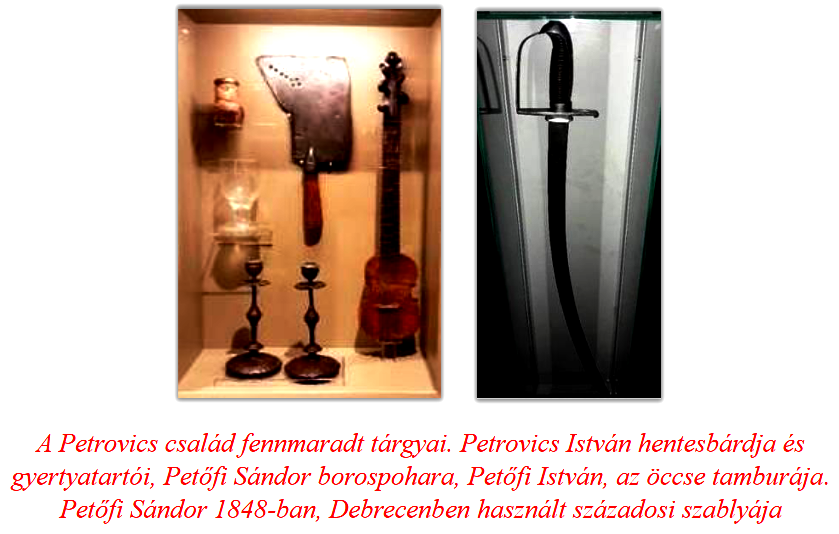

It should be known about the family cemetery on Fiumei Street that István Petrovics and Mária Hrúz, the parents of Sándor Petőfi, and István Petőfi, Sándor's younger brother, are buried here. Júlia Szendrey rests in the family grave. Although she was still officially the wife of Árpád Horváth, the name Sándorné Petőfi, Júlia Szendrey was engraved on the tombstone. Their son, Zoltán Petőfi, rests next to him, in a coffin shared with him.

Júlia Szendrey confessed her feelings on her deathbed in a letter to her father: "My father said that I would be unhappy with Sándor. No woman has ever been given such happiness as I felt when Sándorom and I were together. I was his queen, he adored me and I adored him. We were the happiest couple in the world, and if fate hadn't intervened, we would still be that way today."

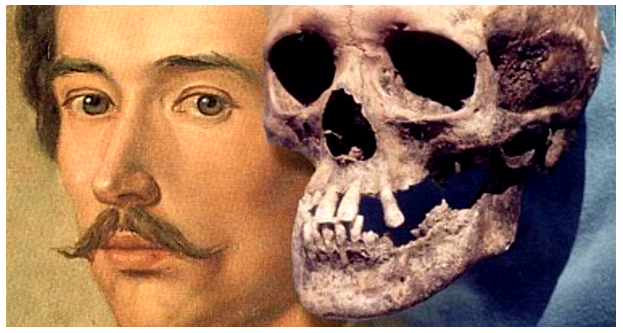

Petőfi in Barguzin

It is difficult to take a stand on a matter that historians, literary scholars, archaeologists, and anthropologists have been debating for decades. The fact that Petőfi did not fall in the battle of Segesvár has been raised before. There are many legends about how he was captured by the Russians and lived in remote Barguzin in Siberia for nearly a decade.

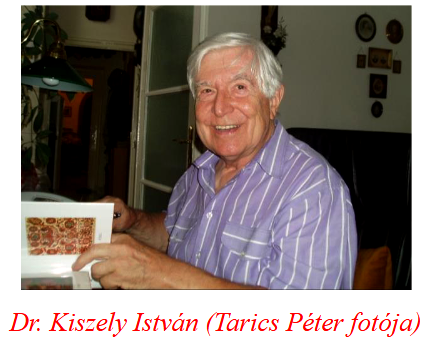

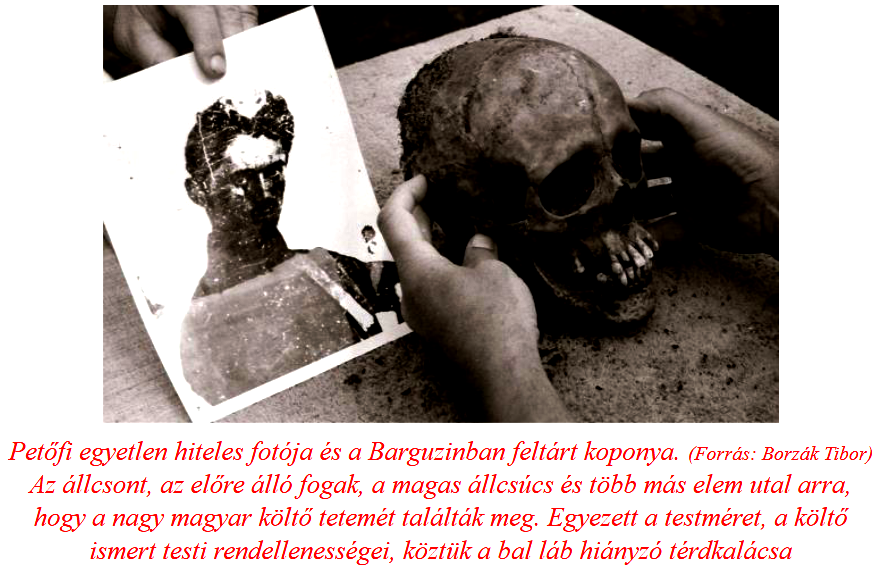

The debate, which continues to this day and sometimes becomes bitter, began in 1989, when Ferenc Morvai , a boiler manufacturer, launched three expeditions to Barguzin as a sponsor. Alexander Petrovich's was found in the settlement, in the "graveyard of the exiles" . asked the renowned anthropologist István Kiszely Kiszely, confirming several anthropological results already carried out earlier, also proved that the skeleton excavated in Barguzin was identical to the remains of Sándor Petőfi.

The news was followed by a huge indignation, the Hungarian academy, the official bodies and the luminaries of the literary life dismissed the Kiszely report as ridiculous. The opposing party found out that the remains were the corpse of a woman, and they began discrediting Professor Kiszely, dissecting her past, who then died in 2012.

After the Battle of Segesvár on July 31, 1849, in addition to the story of Petőfi's death, another story also came to light. The research initiated by Edit Kéri in Vienna, as well as in the tsarist and Polish archives (prisoner of war lists) revealed that Petőfi arrived in Siberia, in the Barguzin prison camp, on January 20, 1851, together with ten Hungarians - via Poland. Hungarian prisoners of the First World War, who returned from the Barguzin prison camp, wrote down that in Barguzin there is Magyar utca, Petőfi utca. I cannot verify the truth of these.

After the Battle of Segesvár on July 31, 1849, in addition to the story of Petőfi's death, another story also came to light. The research initiated by Edit Kéri in Vienna, as well as in the tsarist and Polish archives (prisoner of war lists) revealed that Petőfi arrived in Siberia, in the Barguzin prison camp, on January 20, 1851, together with ten Hungarians - via Poland. Hungarian prisoners of the First World War, who returned from the Barguzin prison camp, wrote down that in Barguzin there is Magyar utca, Petőfi utca. I cannot verify the truth of these.

Records from the last century (19th century) mention a mysterious and strange-behaving stranger named Alexander Petrovich, who was a teacher in the village but spoke Russian with an accent. He also wrote poems.

From time to time, news broke out about Petőfi's stay in Siberia, about a moment of his life there. For the first time, a man came forward in 1860, who spread the word that he had also been there, seen Petőfi, and then it turned out that he was a fraud. The first grave digging took place in 1902, and then it too was forgotten.

Those who reject Barguzini's theory are on the other side of the political spectrum. Their claims - mostly in the tone of mockery - are based on the fact that there is complete uncertainty surrounding Petőfi's disappearance, and the many contradictory claims suggest that the great poet really fell during the battle. Among those spreading the news were fraudsters, swindlers, those hoping for financial gain, those seeking fame, the deceived, the vivifiers of legends. The speculation was strengthened by the news blackout ordered by Haynau. Anyone who dared to utter Petőfi's name could expect to be punished. Mór Jókai broke the wall of silence resulting from fear in 1856, and he was followed by János Arany when they started researching Petőfi's memory.

Precisely because it was about the great poet of the nation, the revolutionary, the genius, the mysterious disappearance, it excited ordinary and learned people. The lords of Vienna feared Petőfi even when he was dead.

The situation today is not much different from the mentioned era, because in nearly a decade and a half it was not possible to open the grave of the Petőfi family in the Kerepesi cemetery. Based on the remains of Mária Hrúz, it would have been possible to clarify the origin of the Barguzin skeleton, but in each case, some official body said no. Is it fair to ask why they are afraid? That way it would have been possible to clarify what the truth is.

It is worth quoting Róbert Hermann , who in 1848/49. is perhaps the best connoisseur of the 1960s war of independence, the author of several books. He claims that an accurate record was made of the captured officers, and Petőfi was in the rank of major, so his identity should have been documented in the event of his capture. At the same time, there is a list containing the names of 10 Hungarian prisoners of war. There are many contradictions.

After the 26 years of disputes and contradictions that have passed since the opening of Petőfi's grave in Barguzin, which began in 1989, the followers of Ferenc Morvai set the date of the funeral for July 17, 2015 in the Kerepesi cemetery.

After the 26 years of disputes and contradictions that have passed since the opening of Petőfi's grave in Barguzin, which began in 1989, the followers of Ferenc Morvai set the date of the funeral for July 17, 2015 in the Kerepesi cemetery.

However, they were not given permission to do so, so the official funeral planned in the grave of the Petőfi family was canceled because the responsible director of the cemetery did not grant permission. Ferenc Morvai and his companions secretly buried Petőfi's ashes that they brought, and this inscription was placed on his tombstone: "Sándor Petőfi, poet, revolutionary, born in Hungary in 1823, died in Siberia in 1856."

Author: Ferenc Bánhegyi

The parts of the series published so far can be read here: 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24,, 25., 26., 27., 28., 29/1.,29/2., 30., 31., 32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46., 47., 48., 49., 50., 51., 52., 53., 54., 55., 56., 57., 58.